MATERIAL

A few weeks ago, I made 16 circuits around Earth immersed in the Orbital novel based on the pragmatics, perspective, and poetry of life on the International Space Station. One of the most notable things author Samantha Harvey brought to my attention is that these astro/cosmonauts aren’t flying so much as falling.

Falling?

Indeed, says NASA, the ISS, as if leaping always from a tower 250 miles up and still pulled by gravity, “falls towards Earth continually due to atmospheric friction and requires periodic rocket firings to boost the orbit.”

Or in a longer explanation aided by NASA flight controller Robert Frost who summons Sir Isaac Newton:

One of the simplest explanations is provided by Sir Isaac Newton in his book Treatise on the System of the World. Sir Isaac describes a thought experiment involving a projectile, such as a cannon ball. He says that if we propel that cannon ball sideways, parallel with the ground, the cannon ball travels a curved path towards the ground, because of gravity. He then says, suppose we increase the velocity at which we eject that projectile. The more we increase that initial speed, the farther the projectile will be able to travel before it hits the ground.

Sir Isaac then imagines we take our cannon up to the top of a very high mountain, so that not only will there be no obstacles in the path of the projectile, but the air will be so thin that it will offer little resistance to the projectile. Does it not then make sense that we could fire our projectile at such a speed that the curvature of its path would match the curvature of the Earth and the projectile would never fall to the ground?

That’s the conceptual essence. The ISS doesn’t fall to Earth because it is moving forward at exactly the right speed that when combined with the rate it is falling, due to gravity, produces a curved path that matches the curvature of the Earth.

And so it goes and goes and goes (you spin me right ’round baby right ’round like a record baby with some boosting along the way so it doesn’t stop), until…it does.

I said I wouldn’t reveal the ending, of Earth, or this novel, but suffice it to say—at least in the fiction—there is a very concerning crack in the Russian module of this hodgepodge contraption and it seems only a matter time until this whole massive (football field-sized) experiment goes bust.

How long?

Decommissioning this specific ISS, explained in this piece on NPR, is in the works for 2030, when it will be disabled and allowed to finally fall freely as is its impulse into the ocean. Not that that will be the end of the ISS mission in general, but the beginning, as with many projects in space these days, of it being privatized. Witness just this week how some ISS visitors came by way of Boeing’s first successful Starliner shuttle, now the second company empowered to drop off astronauts along with SpaceX’s Crew Dragon that has been doing this since 2020. NASA wants to put its energy (and dollars) into deep space exploration, while they are going to choose a contender between firms Axiom Space, Voyager Space, or Blue Origin to outfit a shiny new station. At the age of 26 years currently (and 32 by the end of its life), it’s pretty old for what is effectively a very elaborate assemblage of life support tech jostled nonstop amidst space garbage, with all its cobbled together upgrades making things aboard pretty hectic.

A nice tidying with a new model a la Marie Condo is in order:

“If you see pictures of the station, you’ll think ‘how can they work there?’ It looks cluttered, it looks messy,” Astronaut Peggy Whitson told NPR. She’s spent more time in space than any other woman and is the first woman to command the ISS. Whitson is now Director of Human Spaceflight and an astronaut at Axiom Space, one of the companies funded by NASA to develop a space station.

Whitson said the reason there are cables all over the place is because the structure of the station wasn’t designed for some of the systems it has now. She thinks having a method for making a station even more adaptable to new technology will be important in terms of user experience.

Whitson doesn’t know what technology will be available five years from now. But she said Axiom Space will want to take advantage of whatever they can get their hands on, ideally without wires everywhere.

And even more enticing, a better view with full-body floating capacity:

Whitson told NPR that on the space station Axiom Space is developing, they will have windows in the crew quarters and a huge cupola, what she describes as an astronaut’s window to the world. On the ISS, they have a cupola you can pop your head and shoulders into and see 360-degree views of space and look down at the Earth.

On the proposed Axiom space station, Whitson said the cupola is so large that astronauts will be able to float their whole body in there and have it be an experience of basically almost flying in space.

IMMATERIAL

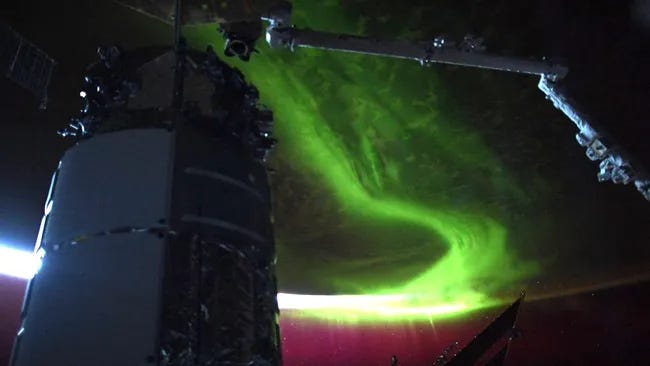

The concept of a new expanded cupola gives me more FOMO than I already had, similar to when I saw a partial but not total eclipse in April (which, by the way, they can see from space not only as the moon passing the sun, but the giant ink stain of the moon shadowing over Earth). And then how achingly lovely the passage in Orbital about ISS’s very special view of the Aurora, which I missed on Earth even when it was available right here in my own local sky—if only when viewed through a better camera or not sleeping.

The airglow is dusty greenish yellow. Beneath it in the gap between atmosphere and earth is a fuzz of neon which starts to stir. It ripples, spills, it’s smoke that pours across the face of the planet; the ice is green, the underside of the spacecraft an alien pall. The light gains edges and limbs; folds and opens. Strains against the inside of the atmosphere, writhes and flexes. Sends up plumes. Fluoresces and brightens. Detonates then in towers of light. Erupts clean through the atmosphere and puts up towers two hundred miles high. At the top of the towers is a swathe of magenta that obscures the stars, and across the globe a shimmering hum of rolling light, of flickering, quavering, flooding light, and the depth of space is mapped in light. Here the flowing, flooding green, there the snaking blades of neon, there the vertical columns of red, there the comets blazing by, there the close stars that seem to turn, there the far stars fixed in the heavens, beyond them the specks that can barely be seen.

By now Shaun and Chie have come, and Anton is at the window in the Russian module, and Pietro in the lab, the six of them drawn moth-like. The orbit rounds out above the Antarctic and begins its ascent towards the north. It leaves waves of aurora in its wake. The towers collapsing as if exhausted, twitches of green on the magnetic field. The South Pole recedes behind.

Roman’s face is like that of a child. Ofiget, he murmurs. A wow snatched from the back of the throat. Sugoii, Chie replices, and Neil echoes it. Remember this, each of them thinks. Remember this.

Remember this, is the title to my friend Steve Adams’s novel I wrote about here before in regards to shape. Remember this is the homage to all things that pass too quickly that we must remind ourselves to savor, not with a camera and recording but with our presence and the attempt of our imperfect minds to capture forever a moment as it’s actually happening, as if we can lock down fleeting time and space and meaning.

For, to continue on the Perspective theme, IT’S A MATTER OF…

…WATER AND SPACE

Orbital makes the fascinating connection between water and space, claustrophobia and agoraphobia. Being a deep sea diver is not unlike floating in zero-gravity:

When Nell went freediving she would think: maybe this is how it is to be an astronaut. Now up here she sometimes closes her eyes and thinks: this is like diving. The slow suspended way the body moves, calmly carried as in water. And the way they move around the labyrinth of the spaceship as if around a wreck—the constricted spaces, the hatches that open into narrow tubes that warren this way and that in near-identical patterns, until it’s hard to know where you started from or where the earth will be when you look out. And when you do look out any claustrophobia becomes agoraphobia in an instant, or you have both at once.

The water and space link taps into something deeply familiar for these astronauts, as if they are suspended in amniotic fluid, taken back to something predating memory but embedded in us innately: our essential incubating time in the womb.

…MOTHER AND BABIES

As they look down from their all-seeing (and precarious) position poised above this delicate Earth, they feel ever more aware their own fragility and dependency on it. Earth is the Mother Ship, their home, creator, while the humans on the ship are really more like sucking babies with their velcro holders and straws and padded gear.

They look down and they understand why it’s called Mother Earth. They all feel it from time to time. They all make an association between the earth and a mother, and this in turn makes them feel like children. In their clean-shaven androgynous bobbing, their regulation shorts and spoonable food, the juice drunk through straws, the birthday bunting, the early nights, the enforced innocence of dutiful days, they all have moments up here of a sudden obliteration of their astronaut selves and a powerful sense of childhood and smallness. Their towering parent ever-present through the dome of glass.

And, it just so happens, the astronauts stay in nine-month stints. The nine months it takes to hatch a baby.

When the six of them talked about their spacewalks afterwards, they described it déjà vu—they knew they’d been there before. Roman said that perhaps it was caused by untapped memories of being in the womb. That’s what floating in space feels like for me, he’d said. Being not yet born.

…LIFE AND DEATH

We are reminded from Orbital of the grandiosity of life along with the mundane, everything mortal, just a matter of time. Even the death of the sun someday, 80 million miles away. The death of these ships (perhaps sooner in the fiction than NASA plans when there’s that disturbing crack on the Russian’s side).

Like the mice, the humans themselves are there as data points, constantly checking their stats, measuring their physical decline. Yet, the difference between the humans and the mice: we somehow seek meaning from these space adventures, to fathom, to fill. Following a calling:

Siren song of other worlds, some grand abstract dream of interplanetary life, of humanity uncoupled from its hobbled earth and set free; the conquest of the void.

We feel the contrasts of coming and going, solitude and community: “The loneliness of being here and the apprehension of leaving here.”

In the arc of history, how recent we are, how compacted now with the acceleration of history and “progress.”

We exist now in a fleeting bloom of life and knowing, one finger-snap of frantic being, and this is it. This summery burst of life is more bomb than bud. These fecund times are moving fast.

…HEAVEN AND EARTH

God or no god, religion or atheism, from here is just the different angle between a similarly astounding universe that achieves the same effect whether heedful or heedless.

Nell wants sometimes to ask Shaun how it is he can be an astronaut and believe in God, a Creationist God that is, but she knows what his answer would be. He’d ask how it is she can be an astronaut and not believe in God. They’d draw a blank. She’d point out of the port and starboard windows where the darkness is endless and ferocious. Where solar systems and galaxies are violently scattered. Where the field of view is so deep and multidimensional that the warp of space-time is something you can almost see. Look, she’d say. What made that but some heedless hurling beautiful force?

And Shaun would point out of the port and starboard windows where the darkness is endless and ferocious, at exactly the same violently scattered solar systems and galaxies and at the same deep and multidimensional field of view warped with space-time, and he would say: what made that but some heedful hurling beautiful force?

Is that all the difference there is between their views, then—a bit of heed? Is Shaun’s universe just the same as hers but made with care, to a design? Hers an occurrence of nature and his an artwork? The difference seems both trivial and insurmountable.

Chie’s mom has died and she is stuck up there not being able to go the funeral on Earth, missing her, missing everything.

There’s that word: mother mother mother mother. Chie’s only mother now is that rolling, glowing ball that throws itself involuntarily around the sun once a year… That ball is the only thing she can point to now that has given her life. There’s no life without it…

No need to speak; you only have to look out through the window at a radiance doubling and redoubling. The earth, from here, is like heaven. It flows with colour. A burst of hopeful colour. When we’re on that planet we look up and think heaven is elsewhere, but here is what the astronauts and cosmonauts sometimes think: maybe all of us born to it have already died and are in an afterlife. If we must go to an improbable, hard-to-believe-in place when we die, that glassy, distant orb with its beautiful lonely light shows could well be it.

The definition of immaterial is interestingly two-fold. You have immaterial as in “unimportant” or “inconsequential” which is not at all the stance I take on what we get from spelunking space. There is rather much material to glean from these risky and pricey endeavors, much scientific data from these grand experiments to teach us evermore about ourselves and our role in the universe, but also the precious depths of the other meaning of the immaterial: the disembodied, the spiritual. We cast our collective soul out into the impossible, the profound.

I love how you mix disparate pieces into a whole. Also, thanks for the reference.

I liked the womb/spacewalk analogy the most. The 9 month stint thing is a pretty perfect coincidence!