When I was a kid, I wanted to be a bird. I fantasized about flight, and the double meaning of flight: escape. Oh how I wanted to soar with wings taut and just glide the air currents the way the upper hawks seem to—leave my house, my school, my town and float far beyond all diurnal troubles. Are these magnificent birds having a good time up there? Are they joy-riding? Do they look down on us as silly blips from a distance, everything just potential prey or not prey, light or dark shadow puppets?

Then, in the mix of all the Carl Sagan and Cosmos forever playing on the den TV in the background as if on a loop, I dreamed of getting higher than that layer of our atmosphere—all the way to outer space, to see the earth from above the earth. I still do. Couldn’t having that perspective solve so many human, and human-caused, problems? Could we not get a better handle on the arbitrariness of so many divisive conflicts and border issues from that vantage point where everything blurs into blues, greens, whites and browns? Couldn’t we feel more protective toward this precious multi-colored marble we inhabit/trash, and want to better save it from ourselves?

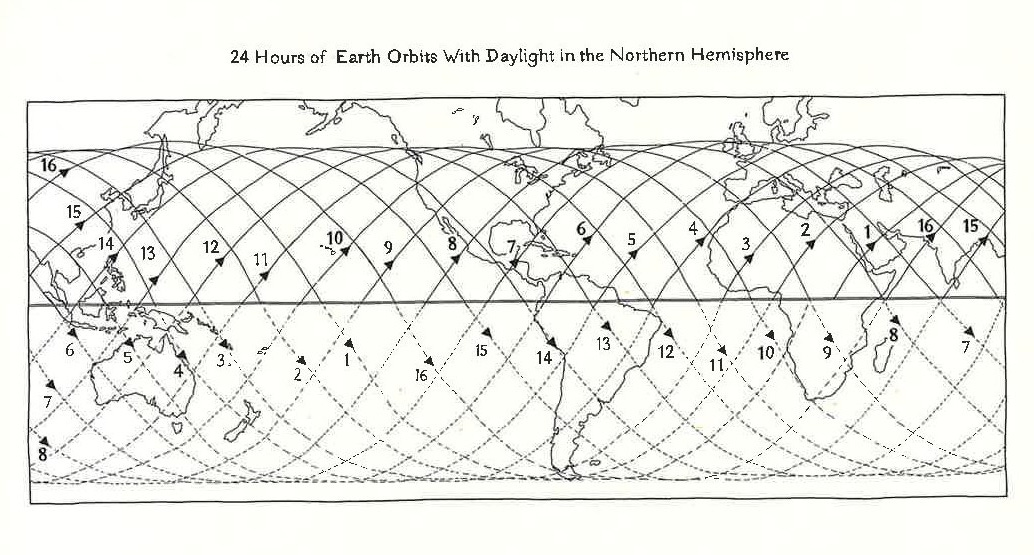

My favorite author of the moment is Samantha Harvey with this slim new fiction, Orbital, which reads anything but slimly. It vibrates with so many layers of beauty that it feels more like poetry you have to put down frequently in order to fathom, spacedream, sigh, sometimes sob (I did that too). It takes us through a day amidst the nine-month stint of the four astronauts and two cosmonauts on the International Space Station, dizzily zipping around and around our globe. Despite the speed of their flight (or, more aptly and astoundingly, fall) around earth—the incessant orbiting that amounts to one orbit per chapter to get us to 16 per day—it’s not a page-turner so much as a page-pauser. In only 200 or so pages, Harvey requires eons and our vast imaginations to take in the magnitude of all of space, all of earth, all the weather and natural formations, all humans and animals and objects, all billions of stars, all of time since the Big Bang.

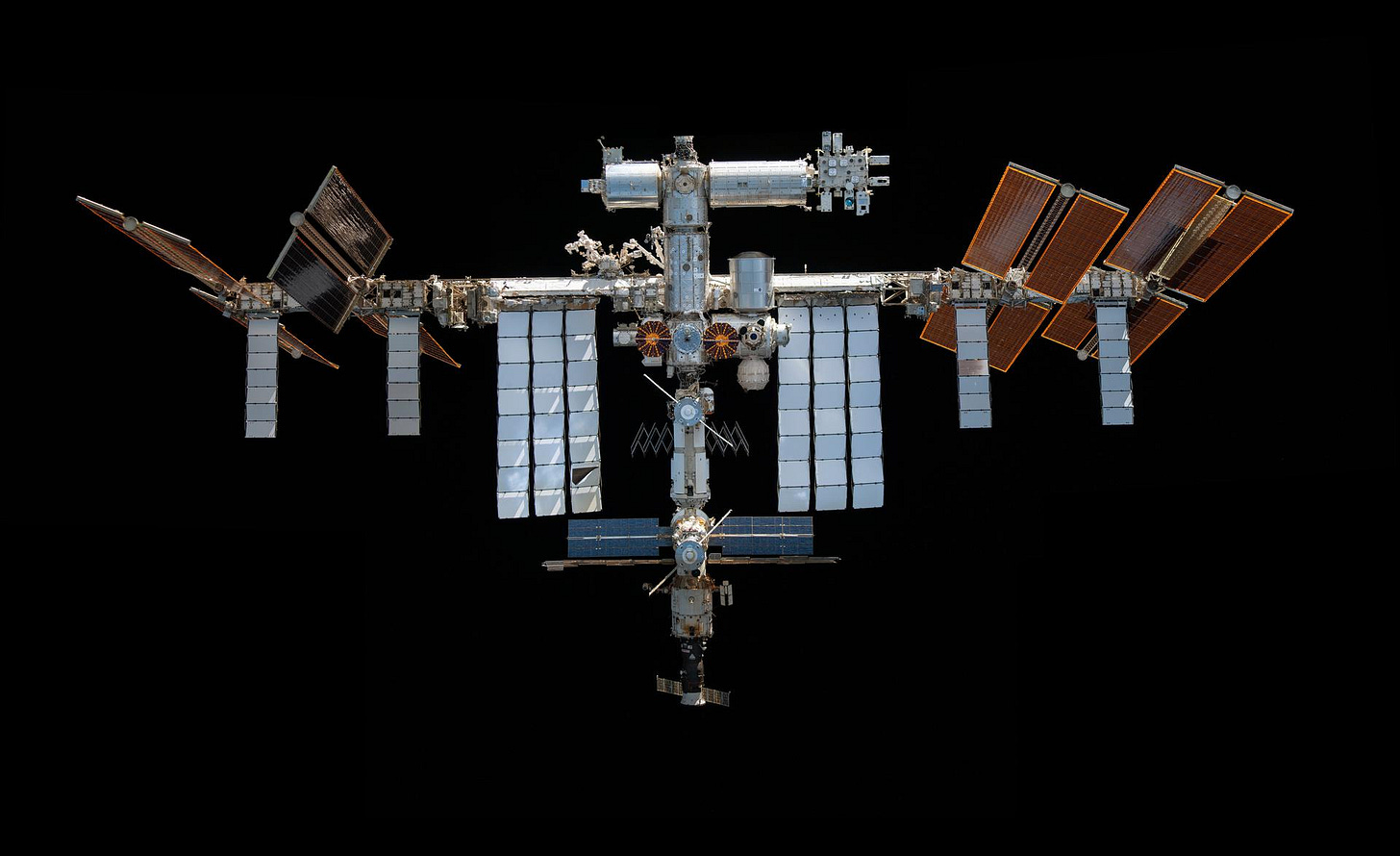

The first note I wrote in the mental margins was “perspective.” Harvey turns every concept every which way to inspect every angle, from near and far, up and down. We feel as if we too are in the ISS, hurtling around earth at 17.5 thousand miles per hour, in what is effectively a tin can (or rather 17 connecting modules of tin can), with these six uniquely diverse crew, at 250 miles above earth. In her story, it happens to be the day a billion-dollar moon crew en route to a new (finally!) lunar landing catapults past them with their goal of traveling 250,000 miles. They are no longer the only humans between here and there. The relativity of days now when they pass 16 sunrises and sunsets in each; the arbitrariness of upright when there’s nothing holding them down, even their tears floating intact past; the blurring of boundaries between countries and peoples when all they see out their windows is one continuous flow between water and land.

Is it necessarily the case that the further you get from something the more perspective you have on it? It’s probably a childish thought, but he has an idea that if you could get far enough away from the earth you’d be able finally to understand it—to see it with your own eyes as an object, a small blue dot, a cosmic and mysterious thing. Not to understand its mystery, but to understand that it is mysterious. To see it as a mathematical swarm. To see the solidity fall away from it.

Chosen for their strength, the astronautical bones are hollowing, their muscles softening without resistance. The test mice they study are beginning to float and fly off and seem joyful in their newfound movement. The humans are the ones who are meant to be special, and yet they are also just test mice, there to measure the effects of this space experiment on themselves. Everyone and all these life-support things around them are just future dust motes, the potential of space junk debris in perpetual orbit.

Another traveller to the beyond Harvey mentions—not bound by earth’s gravity and ringing it the way ISS is, but propelling out and out ad infinitum—are my favorite Voyagers with their dual Golden Records, and the love story with its heartbeat quietly adding romantic rhythm to those faraway missions. So full of hope we are that we’ll make contact with some other intelligent life form someday, so we don’t have to feel so cosmically alone.

We send out the Voyager probes into interstellar space in a big-hearted fanciful spasm of hope. Two capsules from earth containing images and songs just waiting to be found in—who knows—tens or hundreds of thousands of years if all goes well. Otherwise millions or billions, or not at all. Meanwhile we begin to listen. We scan the reaches for radio waves. Nothing answers. We keep on scanning for decades and decades. Nothing answers. We make wishful and fearful projections through books, films and the like about how it might look, this alien life, when it finally makes contact. But it doesn’t make contact and we suspect in truth that it never will. It’s not even out there, we think. Why bother waiting when there’s nothing there? And now maybe humankind is in the late smash-it-all-up teenage stage of self-harm and nihilism, because we didn’t ask to be alive, we didn’t ask to inherit an earth to look after, and we didn’t ask to be so completely unjustly darkly alone.

Our solitude and ultimate aloneness come into focus in these tight quarters, but also inescapable and haunting human connection, their ties to each other and to the invisible people hidden amidst the landscapes under clouds below. The astronauts’ dreams start mirroring each other’s, their sleeping and waking thoughts full of home and their histories as they look down and try to find their part of their countries, where their children, their spouses, their dying/dead parents might be. The solidity of the dreams vs. the surreality of their waking lives in this home away from home had me thinking: how relative are these varying states of consciousness too. Could we be dreaming when we think we’re awake and awake when we think we’re dreaming? Those moments when you awaken in the middle of a dream so vivid with someone dead or gone and ache to go back with them but you can’t quite re-access that magic space again, and you weep anew with grief. Is that the real life in there and this—the out here, supposedly—is the fiction? All that we see, feel and think is just brain projection.

Therapy is a touchstone for me, it helps me sort my scrambled head, even if only to tease out what I already know that got buried. I am continually battling with my own anxiety-driven knee-jerk responses to stress (these teens!) and ignoring the wisdom that I should do better in those moments. But cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has handy tips for flipping the script, should you remember to employ them. In hot moments when your reactivity is getting away with you, stick your head in the freezer for a few seconds, for instance. Or remove yourself from the scene to find an “orienting response” at the border of things—the treeline, the water’s edge.

I regularly love the ISS for this: from the perspective here on earth to look up and sometimes actually see that very reflective contraption as it arcs over like a different, higher, faster airplane on its own unique track. To take us outside of ourselves and our petty lives for an instant and know there are however many bodies in that ship right now, along with however many study mice and plants, and whatever else velcroed down to keep it from floating off, testing the limits for us of space, time, science, themselves. In order that the next mission, and the next crews, might go further.

They’re the specimens and the objects of research who’ve forged the way for their own surpassing.

There’s so much loveliness to quote from Harvey’s Orbital, I’ll save more for next week.

In the meantime, and I recommend you do, you can sign up for alerts to know when the ISS is passing through your particular spaceview. NASA’s Spot The Station feature will text or email you if the space station is visible near you (choose the dot closest to you on the map), by night when you can actually see it. The alerts will come for a year, then they will remind you to renew. From the FAQs:

WHEN

The Spot The Station website will only notify you of ‘optimal’ sighting opportunities—that is, sightings that are high enough in the sky (40 degrees or more) and last long enough to give you the best view of the orbiting laboratory.

HOW OFTEN

The space station is visible because it reflects the light of the Sun—the same reason we can see the Moon. However, unlike the Moon, the space station isn’t bright enough to see during the day. It can only be seen when it is dawn or dusk at your location. As such, it can range from one sighting opportunity a month to several a week, since it has to be both dark where you are, and the space station has to happen to be going overhead.

WHAT

The space station is Earth’s only microgravity laboratory. This football field-sized platform hosts a plethora of science and technology experiments that are continuously being conducted by crew members, or are automated. Research aboard the orbiting laboratory holds benefits for life back on Earth, as well as for future space exploration. The space station serves as a testbed for technologies and allows us to study the impacts of long-term spaceflight to humans, supporting NASA’s mission to push human presence farther into space.

And to think, I’ve been calling it “earth” here, as does Harvey in her book actually, which is more by definition just the dirt on this planet, e-a-r-t-h, how funny, when you look at and say it a few times, it becomes such a strange word for something both so big and small. But, mind you, it’s singular Earth, says NASA, super special with a capital E.

Respect. Perspective.

And I don’t want to give away the ending, but it does all end.

At the brink of a continent the light is fading. The sea is flat and copper with reflected sun and the shadows of the clouds are long on the water. Asia come and gone. Australia a dark featureless shape against this last breath of light, which has now turned platinum. Everything is dimming. The earth’s horizon, which cracked open with light at so recent a dawn, is being erased. Darkness eats at the sharpness of its line as if the earth is dissolving and the plant turns purple and appears to blur, a watercolor washing away.

I do think I am mostly Earth-bound, so it's good for me to get your reports from the field, a field I'm not likely to travel on my own. But back to Earth, and birds, which I love, (and I know I'm sliding off subject) it is a bit of a shock when you become a parrot "owner" as I did, and come to realize, at least with this species, that relationships are the essential core and necessity of their life, much more than flight. Flight's mostly just how you get somewhere (watching peregrine falcons or chimney sweeps and the joy in their movement indicate to me their experience is different). But an inside parrot with a good relationship (which takes work, believe me), will be happy as a clam (clams are happy, right?), but if there is no relationship, or a sorry one, the bird can easily fall into irretrievable madness. The thought that fills me with tenderness and awe is the idea that there are flocks of these creatures flying all over the world with this degree of necessity for connection. I would like to come back in my next life as a bird, and if not a parrot, then possibly a corvid. But I'd take most anything, as long as it can fly (yes, I want flight too; don't we all?). But not in the future unless it's another planet. Or maybe 1000 years ago if it's here. (See? I did sort of manage to bring it back to planets.)

I got stuck in Orbital and stopped! I had to return to the library but maybe I’ll give it another go sometime.