For a person who has the tendency to skew living 75% in my brain and 25% in my body, I’m surprisingly very visual. I like translating intangible feelings to Venn diagrams and to each project its own tab in my master-spreadsheet. Plans must be penned to be realized, if only in endless lists that beget more lists. Shapes are satisfying. My novels—back in the pre-childbirth times where I had to time to write such things—generally started as amorphous word-vomit blobs that slowly collected around a form, and the form perhaps saved the whole enterprise. It was liberating for me to declare Four Corners is all squares, Degas is a parabola, because, as I like to say, you are free when you choose your cage.

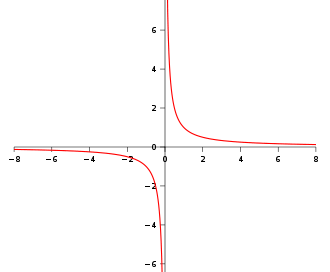

My first book came from this image of an arc approaching asymptote, times two. Degas Must Have Loved a Dancer is the story of two lovers who never quite get together, themes of infinite approach and artistic obsession, a line getting closer and closer but doomed to never intersect the other line doing the same thing in another quadrant. Desire drives the telling. Two equal, diverging lives, too similar to meet in the different planes they inhabit. Star-not-enough-crossed lovers.

Then you have my second book, Four Corners, which as the title suggests is all about squares for a family of four. This really factors into, and frames, each and every scene, which are always set in a square-shaped place—an angled table, a four-door car, a four-postered bed.

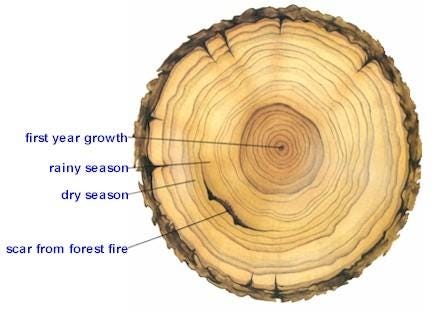

Finally there’s my third book, pending self-publishing ASAP since it’s been too long lost in limbo, based upon concentric rings of tree growth. The title is The Birches, with the central scene this fraught moment where the main character as a child peels the bark off a bunch of poor birch trees. All other scenes emanate out from or fixate on this central moment. So as opposed to your typical book that starts from the beginning and works its way in linear fashion from A to B, mine begins in the middle and works it way out. (In theory; this was easier said than done!) I am fascinated by the way each ring of a tree reveals its history—one ring has meager growth due to a fire, another takes a leap in a season of much rain—and try to reflect such “rings” in the narrative arcs of a family’s history.

Each book’s “image” works in both literal and figurative ways. The central organizing principle becomes a player in itself. However, with each book, these were ideas that were likely way more apparent to me as the writer rather than overtly there for any reader. Most readers would probably not even notice (consciously at least) and it wouldn’t do the book any disservice not to notice. Having this image in my mind helped me go about the daunting process of organizing/completing these books; it gave me something fun to work with that begat its own set of related ideas, demanding its own rules and language. Whether or not the reader can decipher all this, I would hope it certainly adds to the depth of meaning of each book. When I say form = content as I used to in my former life as a writing teacher, there’s the example: a book about trees whose structure happens to resemble them.

A container, as we learned in recent submersible news, is everything. But in this regard, I wouldn’t argue for it being perfectly sealed, rather just the loosest idea of scaffolding that maybe only guides the writer. The reader may sense a feeling of being held, in good hands, but not too tightly. You don’t want them feeling claustrophobic and constricted, as if the characters have none of their own autonomy (and can never come truly alive). They can at least trust that the world being created before them has its rules, that nothing is arbitrary, but there’s also room for change and surprise.

I enjoyed hearing in Steve Adams’s recent interview (called The Big Texas Author Talk) about his expertly crafted debut novel, Remember This, that he too sees shapes. At first the novel, which was long in coming to fruition and seeing the light of publishing, was set fully in New York City of 1988 (a city then clogged with grit and graffiti, and tragically, plagued by AIDS—rubbing up against the rise of computers and gentrification). As rich as that landscape was, he (or rather an editor) felt the story was still falling flat. Later it occurred to him to add a whole thread of alternating years and chapters with childhood-in-Texas scenes. In the present-day plot of NYC, it’s all investment bank offices and an affair with his intriguing boss Alena. Our adrift protagonist John is the other man in a tantalizing yet agonizing love triangle. But in the back story, he’s the protective, doting younger brother to a trio of older sisters, who one-by-one when it’s their time to fly the coop, leave their intense home with an alcoholic mother passed out in the living room chair. It’s an inevitable march of hope and heartbreak as each sister must move beyond where their little brother can reach, let alone save, them. Author Steve says that he pictured the sisters as the top points of a diamond shape with the younger brother at the bottom (arguably two triangles, stacked). NYC is the external plot (our character loves to wander the streets endlessly), while TX is very interior, in the fraught tangle of the troubled yet loving childhood home.

Steve, once a playwright and also a professional coach and editor, offers plenty of useful, solid nuggets of writing wisdom in this interview. In addition to the shape of the container he hangs things on in the background, there’s the almost musical shaping element of “rhyming action” where motifs repeat, each in a slightly different way that invokes nuances of expanded feeling. It’s like choreographing an orchestra in which a few note phrases repeat and shift slightly each time, resonating further and building character, expanding the story. The young boy runs after each car of each departing sister, giving them a push off into their dubious futures painfully separate from him. He also constantly brushes their hair—it’s something of his love language—so when a hairbrush appears in the modern-day scenes with his lover, it’s an aha moment that makes the reader take further notice and start making their own connections on the echoes between past and present, sisters and lover.

“The whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” Steve says. And because in his case I want to picture that as composed of adjacent triangles, I keep thinking of this song that’s been stuck in my head by my favorite band of the moment Alt-J.

Tessellate, such a beautiful word, means to decorate or cover a surface with a pattern of repeated shapes that fit together closely without gaps or overlapping. The setting of this video recreates Raphael’s classic painting from the Italian Renaissance of the early 1500s, The School of Athens (pictured on a dude’s t-shirt at the opening). Originally stocked with the greatest hits heroes of ancient philosophy, arts, math and science—Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras, Euclid, Socrates and many more—now it’s a metal-grilled gang hanging with the hot ladies and their triangle symbols.

Bite chunks out of me

You’re a shark and I’m swimming

My heart still thumps as I bleed

And all your friends come sniffingTriangles are my favorite shape

Three points where two lines meet

Toe to toe, back to back, let’s go

My love, it’s very late

’Til morning comes

Let’s tessellate

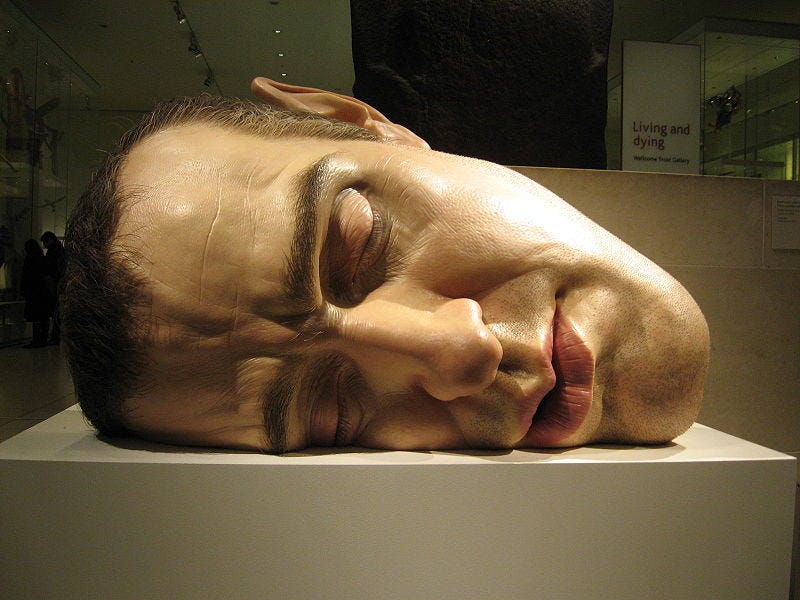

Or what if such artistic tessellation comes in the form of implanting individual hairs into the photorealistic skin of a faux giant?

Ron Mueck, whose work I saw once at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, does these incredibly lifelike sculptures of subjects like a massive newborn baby, misshapen cone head and all. There was a video you could watch in the gallery of all the layers going into this hyper-perfection, the scaffolding of chicken wire, the plaster, the implanting of each and every hair with a syringe. So many steps behind the scenes that result in this thing that looks so lifelike it seems as if it might just scream and yet it’s beyond lifelike, larger than life, since many of his sculptures are super-sized and somehow exaggerated for the most emotional impact. This is the process of writing, layer by layer, to achieve an effect that looks effortless, that seems realistic but strives for the biggest bang.

This insightful interview with the artist about the making of a piece called Big Man has the author summing up the magic of his many-layered technique:

Part intuitive, part willed, his multi-staged process involves a series of experiments and discoveries. Far from a servile copyist of nature, he reveals the need of making selective adjustments to maximize the physical and emotional aura of his figures. In the end, Mueck’s success hinges on faith and control. Through mastery of his materials in a seamless, seemingly effortless way, he awakens our willingness to believe in images that our imagination keeps alive.

I also think of James Joyce and how he supposedly wrote the (oft-cryptic) Ulysses layer by layer, threading the book with one motif (as simple as adding hints of the color blue, for example), and then going back and doing another and another, almost like weaving.

If you’re not a writer, the theme still applies. I circle back to the initial premise on the value of applying these shapes to your life. I swear that just the act of drawing concentric rings in my notebook and filling each ring with specific goals rapidly changed my life. The first innermost circle was where we begin, with ourselves, my body and brain, with the rings rippling out from there as if from a stone plopped in pond water with things increasingly distant. Second circle: home/family. Third: friends/work. Fourth: travel/projects. Fifth: outerspace/deep sea (I didn’t go that far, but you get the idea). Each ring had immediate, attainable goals to work on, and only after setting the first ring in motion—take care of your own oxygen first—would I move on to focus on the second. This is how in rapid succession in 2021, self-improvement lead to family therapy, renovating my house, transitioning to a new career, buying a second property, putting myself on a dating app. Just some circles. In the span of months. Bullseye!

Unlike writing a novel where you have to create the actual clay first, when it comes to remastering your own life, the materials are already there. You’re just an editor now. Shape-shifting.

Love the image of plot as graph and shape. I’m such a math nerd. 😂

I love metaphors as frameworks. Shapes are like the simplest version of this concept in practice.

As a visual artist in my 20s, I learned pretty early on that it was useful to have a constraining framework. That sounds weird, but the tension between the restrictions and my desire to be creative really produced some great results. Since then, I've tried to use similar frameworks to help with the writing process. Naturally, this sort of thinking resonates with me.