There's No Place Like Gnome

In your garden or abroad

I interrupt my plan to dig into Yellowjacket’s cannibalistic tendencies, no joke, to try to get into the mood of the season, refrain from eating any people, and share some holiday cheer already.

On that high note, my all-time favorite Christmas movie is Amelie, which has nothing to do with Christmas, save for its green and red tones, its quick-witted charm, and the fact that I brought my parents to see it, complete with subtitles, on Christmas Eve the year it came out. Which was 2001, moments after 9/11 rocked our collective world, and we really needed some cinemagic to soothe our souls. Amelie with her cute French bob and impish interest in the little pleasures of life—and the soundtrack!— delivered. The contemporary tragedy rocking her world was the death of Princess Diana after a paparazzi car chase in a Paris tunnel, and the film weaves people reacting to it in their daily lives, with news clips and headlines of the Lady Di disaster throughout. Amelie, ever the introvert, discovers a small secret tin hidden in a cavity behind her bathroom floor tiles that day of the death news, which sets her off on a mission to return this childhood treasure box to its rightful owner. Along the way she brings accidental or intentional happiness to many, exacts some minor yet deserved revenge on this grumpy bully of a shopkeeper, and conspires to connect, if clumsily, with her stranger love-at-first-sight. One significant side plot has Amelie kidnapping her stilted father’s garden gnome. Her flight attendant friend takes him along on all her international stops, snaps a gnome pic in each, and sends back to the dad this unlikely travelogue. All very mystifying until the gnome returns and her dad is finally inspired to see the world at last himself. Mission accompli.

GNOMENCLATURE

Before there were garden gnomes with silly red pointy hats, there were just gnomes and supposedly reared by a forefather of, however unlikely this may sound, modern medicine.

The word gnomes derives from the Latin gnomus (from Greek gēnomos) meaning “earth-dweller.” As outlined in this Glorian post, Paracelsus, Swiss alchemist and physician of the 16th century, in his free time constructed a four-chambered mythology. He divided creatures into “elementals” or Nature Spirits of four distinct groups—gnomes (associated with earth), undines (water ), sylphs (air), and salamanders (fire), which I can play with further another time. He figured, humans, by the way, could be categorized by the fifth element (ether).

Other writers further fleshed this out this vision. From Faena.com:

In his book Mermaids, Sylphs, Gnomes and Salamanders: Dialogues with the Kings and Queens of Nature, William R. Mistele introduces these mythical beings, by contextualising their symbolism to establish a scheme of psycho-behavioural relations.

Gnomes, the beings more closely linked to the earth, embody the desire to work with physical matter, transforming the world so that things can have a truly lasting value. They are the bastions, the yearning, the support, the heat of a household. At times their fidelity might seem stubborn, but they are always brave.

By this definition, I almost think of Amelie herself as such a force of gnomic energy, adding the heat and substance of deeper meaning—and romance—to everything around her. But how did such earthy gnome effigies actually get grounded in our gardens?

A brief history of garden gnomes from the Washington Post illustrates that apparently some of the most interesting things (like the Wolpertinger we hung out with a few weeks ago) come from 1800s Germany.

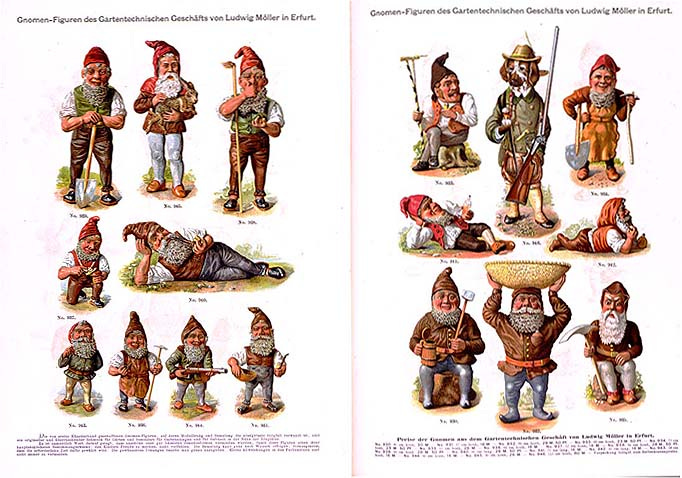

There are plenty of little characters in mythologies from around the world—including the Egyptian god Bes, and brownies, house spirits in British and Scottish folklore—and small stone figures started appearing in Italian gardens during the Renaissance. However, according to [Twig] Way, [garden historian and author of Garden Gnomes: A History] what have become known as garden gnomes in the United States and England can be traced to dwarf statues that originated in Germany’s Black Forest region around the early 19th century. They were initially carved out of wood; by the mid-19th century, they were cast in terra cotta and porcelain. They weren’t a garden fixture, though; they were hand-painted, usually about three feet tall and expensive, so they were intended to be displayed inside as pieces of art.

Eventually some Sir named Charles Isham is credited with getting them out of the house and into his British garden—ordering in bulk from Germany, from perhaps a catalogue like this, in the 1840s.

As most things associated with Germany were avoided during the WWI and II, the gnomes lost popularity but grew back into favor in the 1950s and 60s. Now mass-produced and available in concrete, they became smaller and cheaper, and available to more regular folks and their yards. Eventually the trend travels to the US largely thanks to Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Then there was an illustrated fictional Gnomes book that sold upwards of a million copies and gnomes went viral in 1976.

The collaborators claimed their fictional work was based on observations of actual living gnomes in their native Holland, documenting history, housebuilding, courtship and copulation (which was apparently so robust that the female gnomes almost always gave birth to twins). [Rien] Poortvliet’s playful pictures of gnomes rubbing noses, helping injured animals and building snug underground cabins painted them as endearing, warmhearted characters full of good intentions.

When everything gets culturally ugly (the 1980s), American gnomes seem to get subverted with topless versions and farting models. “It was downhill from there. Now it’s possible to find statues of gnomes mooning, sitting on the toilet and vomiting rainbows. We think Isham would not approve.” Fast forward to Amelie, which cleaned the gnomes up again but launched the figurines into this other realm which apparently inspired Travelocity’s Roaming Gnome ad series of 2004 and became the brand’s de facto mascot.

If anyone can speak to what I perceive as the uncanny intersection of Santa, Rip Van Winkle, Papa Smurf, and Gnomes who sport red pointy hats and/or long white beards, I’d love to hear about it.

KAFKA’S OTHER TRANSFORMATION

The tale of the traveling gnome had me stumble upon a similar story, supposedly somewhat based in fact and involving our buggy author Kafka.

Snopes.com breaks down what might be true and false in this article on Kafka and a traveling doll. Lit legend has it, that at the age of 40, Franz Kafka (1883-1924), childless and unmarried, was walking in a park in Berlin when he came upon a girl crying about her lost doll. They made a date to search for it together the next day, which proved unsuccessful. So, being the writer he was, Kafka handed the girl a letter, supposedly from her doll, saying, basically, not to worry, but I’m off to see the world and will send you letters from my adventures. Which, apparently Kafka continued to send to the girl throughout the rest of his short life. Eventually he brought her a replacement doll but the girl rejected it as not resembling the original. Kafka had another letter at the ready, saying, “my travels have changed me.” Soon Kafka was dead.

Barring copies of the doll letters themselves, some version of the story—likely minus any actual changed doll in the end—has been backed up by Kafka’s partner Dora Diamant, who lived with him in his last year in Berlin in 1924. And it made it into popular culture in various ways.

Paul Auster included the doll story in his 2005 novel The Brooklyn Follies, and it inspired the March 2021 graphic novel Kafka and the Doll by Larissa Theule and Rebecca Green.

In 1982, Ronald Hayman mentioned the doll story in his biography of Kafka, and in 1984, the literary critic Anthony Rudolf published a version of the story, translated from French, in the literary supplement of the Jewish Chronicle. Rudolf prefaces the tale by describing it as a “simple, perfect and true Kafka story,” which Diamant had originally relayed in person to Marthe Robert, a French Kafka translator, in the early 1950s.

In Robert’s account, the traveling doll after three weeks got married off for the sake of convenience. In any case, the story has provided more comfort ultimately and a longer life in legend than any doll itself, echoing through its various depictions.

The Tom Glass character in The Brooklyn Follies describes the deeper meaning:

By that point, of course, the girl no longer misses the doll. Kafka has given her something else instead, and by the time those three weeks are up, the letters have cured her of her unhappiness. She has the story, and when a person is lucky enough to live inside a story, to live inside an imaginary world, the pains of this world disappear. For as long as the story goes on, reality no longer exists.

Now if only we can send these peevish elves-on-shelves farther afield.

Curiously, a very brief musical queue from the ending of the first phrase of 'Gnomus' from Ravel's orchestration of Mussorgsky's "Pictures at an Exhibition" seems to be heard as Amelie spins down a seat in the photo booth before discovering the Photo Booth Mystery Man. (Odd placement in the film though.) Were there other musical quotes associated with gnomes in the film?

Any idea if Kafka's doll (or the stories surrounding it) inspired the Flat Stanley craze?

I'm pretty sure I had a friend whose mom collected gnomes, but that memory is still really fuzzy.