As often happens now at this on-the-precipice-of-too-late stage of our climate crisis, there is a bug out of place and out of time. A fly in my Northeast winter bedroom attacking the light in a frantic way that echoes in the night of my insomnia. Or, this summer when I awoke to the loud mechanical sound of a lost lanternfly hovering above me, taunting, in the moonlight.

What comes to me in these moments is the enduring line from the Emily Dickinson poem,

I heard a Fly buzz - when I died -

Or, since I had kids, some version of the nursery rhyme: “There was an old lady who swallowed a fly, perhaps she’ll die.”

Or, from The Fly movie of 1986:

“Be afraid, be very afraid.”

Welcome to week 2 of my Monster Mash: this time themed on bugs, if you can stand it.

My kids actually come in part from bed bugs. There was an infestation in my boyfriend’s Brooklyn apartment that lead him to move in with me; I got pregnant; we got married. The engagement ring—since we decided to celebrate and not snub the bugginess of this—was actually custom-built around an ancient moth fly in amber. Despite this odd origin story and my ongoing efforts to foster a peaceful alliance/appreciation between my kids and all things in the natural world for their entire conscious life as Girl Scouts, hikers, and happy campers, now as teens they still emphatically think insects are monsters. To which I always encourage them to put themselves in the bugs’ shoes. (Not that bugs have shoes, but according to the linguistic trend I wrote about that took off in the 1920s flapper era, fleas have eyebrows, bees knees, and ants pants.) Imagine, I tell them, how monstrous you must seem to a bug.

This doesn’t fly—pun intended—except in the case of “cute” lady bugs who get a pass since they are round, red and dotted. Until the day, in our usual walk through the legendary Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, we came upon a particular mausoleum just covered with them. There was a temple of the dead next door not covered in such lady bugs; same for the tomb adjacent on the other side. Only this one lucky enough to have hundreds of little red critters crawling all over it for no apparent reason. So now even lady bugs aren’t okay with my kids either.

Size matters. Take what one small bug can be in grossness, weirdness and annoyance factored in with the simple fact that you, if non-Buddhistically inclined, can easily just squash it, compared with the complications that ensue when a grown man suddenly turns into a man-sized cockroach.

In Franz Kafka’s short story “The Metamorphosis,” Gregor has the rudest awakening:

One morning, when Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin. He lay on his armour-like back, and if he lifted his head a little he could see his brown belly, slightly domed and divided by arches into stiff sections. The bedding was hardly able to cover it and seemed ready to slide off any moment. His many legs, pitifully thin compared with the size of the rest of him, waved about helplessly as he looked.

“What’s happened to me?” he thought. It wasn’t a dream.

Most interesting to me in this saga, which I first read ages ago but felt compelled to reread recently, is how Gregor’s first and primary concern is how will he get to work in this condition. That impulse reminds me of so many anxiety-fueled nightmares I’ve had wherein I can’t get to the very important thing I need to get to (a test, an interview) because of myriad mitigating factors that render me effectively paralyzed.

Gregor adjusts to his new buggy nature and biology (coming to enjoy “hanging suspended from the ceiling” and forming “the habit of crawling crisscross over the walls”) as his family outside of his bedroom (he’s an adult living with his parents and sister) grows increasingly distressed/repulsed. To the point where his father pitches an apple at the son that breaks through his carapace and sticks inside his body, debilitating him, and the sister, who once at least kept tending to the new format of her brother, now just calls him an “old dung beetle” and seems to be losing interest in even leaving him food scraps.

As Gregor rots and grows more pathetic by the hour, he becomes the picture of depression:

What’s more, there was now all the more reason to keep himself hidden as he was covered in the dust that lay everywhere in his room and flew up at the slightest movement; he carried threads, hairs, and remains of food about on his back and sides; he was much too indifferent to everything now to lay on his back and wipe himself on the carpet like he had used to do several times a day.

Gregor releases his attachment to living, having previously discarded the desire to get to work, and his family comes to decide that this is not their son so they no longer have to feel anything for this aberration. “It’s got to go,” shouted his sister, “that’s the only way, Father. You’ve got to get rid of the idea that that’s Gregor.”

Gregor dies, and the tragic part of the story in the end is that it’s not even about him and his wild metamorphosis. The remaining family gets out of the house for the first time in months, into the optimism again of the warm sun of the country, and finally free of Gregor-as-bug, they can look ahead to better things. Namely, if their son can’t get to work to help them economically, they can at least have a daughter who will marry well. Perhaps the story is really about the girl and her important transition into a woman, who gets the last words:

All the time, Grete was becoming livelier. With all the worry they had been having of late her cheeks had become pale, but, while they were talking, Mr. and Mrs. Samsa were struck, almost simultaneously, with the thought of how their daughter was blossoming into a well built and beautiful young lady. They became quieter. Just from each other’s glance and almost without knowing it they agreed that it would soon be time to find a good man for her. And, as if in confirmation of their new dreams and good intentions, as soon as they reached their destination Grete was the first to get up and stretch out her young body.

Because I adore odd dusty corners like the intersection of etymology and entomology, I had to explore what kind of a bug we’re actually talking about here. One translation might say “cockroach,” while another “big beetle.” What is this creature that Gregor becomes? Apparently Kafka intended his metamorphosis to remain more metaphorical. From an article in OpenCulture:

But the German words used in the first sentence of the story to describe Gregor’s new incarnation are much more mysterious, and perhaps strangely laden with metaphysical significance.

Translator Susan Bernofsky writes, “both the adjective ungeheuer (meaning “monstrous” or “huge”) and the noun Ungeziefer are negations—virtual nonentities—prefixed by un.” Ungeziefer, a term from Middle High German, describes something like “an unclean animal unfit for sacrifice,” belonging to “the class of nasty creepy-crawly things.” It suggests many types of vermin—insects, yes, but also rodents. “Kafka,” writes Bernofsky, “wanted us to see Gregor’s new body and condition with the same hazy focus with which Gregor himself discovers them.”

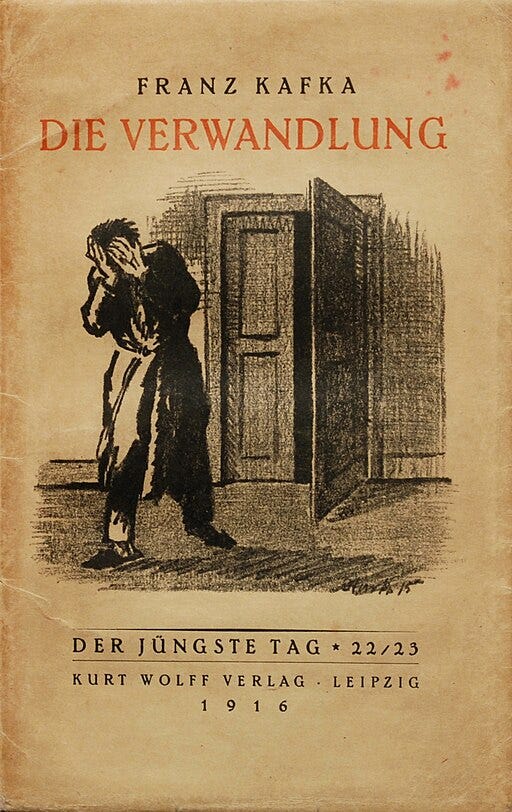

For the sake of keeping his bug more vaguely open-ended, Kafka wanted no visual depictions of it shared. The cover of the original “Die Verwandlung” displays a distraught man with no trace of what he becomes.

It’s likely for that very reason that Kafka prohibited images of Gregor. In a 1915 letter to his publisher, he stipulated, “the insect is not to be drawn. It is not even to be seen from a distance.”

As happens with great pieces of enduring literature, becoming part of the Canon means the story experiences many shifting depictions and reinventions, a metamorphosis ongoing ad infinitum. Enter Director David Cronenberg’s The Fly, which sprung from the head of George Langelaan’s short story that appeared in Playboy in 1957, and the first movie that shortly followed in 1958 starring Vincent Price—all echoing and inspired by Kafka’s original giant insect. (I couldn’t find the actual text of The Fly story, but you can listen to a five-part narration on YouTube that starts here.)

In Cronenberg’s Fly, scientist Dr. Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) has the hubris to put himself in his teleportation machine, unaware there’s a fly in it. Getting reconstituted and fused with fly at first makes him viral, sexy and strong, which his girlfriend Veronica (Geena Davis) initially finds appealing were it not for those few harsh hairs sprouting from his shoulder blade. But soon it’s too much for her to bear when the transformation degrades him into a disgusting mass of humanoid raw hamburger—ultimately resembling his first failed experiment that seemed to turn that poor monkey inside out.

Of his conversion, Seth says:

I’m an insect who dreamt he was a man and loved it. But now the dream is over... and the insect is awake.

And when he’s really high on fly hormones, it’s headfirst into the plasma pool:

You’re afraid to dive into the plasma pool, aren’t you? You’re afraid to be destroyed and recreated, aren’t you? I’ll bet you think that you woke me up about the flesh, don’t you? But you only know society’s straight line about the flesh. You can’t penetrate beyond society’s sick, gray, fear of the flesh. Drink deep, or taste not, the plasma spring! Y’see what I’m saying? And I’m not just talking about sex and penetration. I’m talking about penetration beyond the veil of the flesh! A deep penetrating dive into the plasma pool!

Cronenberg himself wrote about Kafka’s Beetle vs. his Fly and its forebears in this excellent essay in The Paris Review from 2014. On becoming the mortal age of 70, Cronenberg admits feeling a shock similar to waking up as a bug:

What about me? Is my seventieth birthday a death sentence? Of course, yes, it is, and in some ways it has sealed me within myself as surely as if I had suffered a total paralysis. And this revelation is the function of the bed, and of dreaming in the bed, the mortar in which the minutiae of everyday life are crushed, ground up, and mixed with memory and desire and dread. Gregor awakes from troubled dreams which are never directly described by Kafka. Did Gregor dream that he was an insect, then awake to find that he was one?

Kafka’s bed to bug adventure ends in death with minor consequence, under the rug he goes, while Cronenberg’s fly is a terror that rattles our ideas of what it means to be human—perhaps any power is an illusion we will wake up from. Awaken into the fact of our mortality and that awful buzz of Emily Dickinson’s dread fly of death:

There interposed a Fly -

With Blue - uncertain - stumbling Buzz -

Between the light - and me -

And then the Windows failed - and then

I could not see to see -

So much here: I pain over these and strive for effortlessness - sometimes that happens more than other times, but I appreciate it seems that way!

Common eccentric enemy is a great way to put that and very true. I often don’t know if I’ll survive their (loving) disdain.

I missed your newsletter, is it archived?

The Fly is very fluid! Just gross. I do look forward to watching the original. Part of my process ideally would be all the time to do all the watching/reading I allude to :)

I took two years of German in college. Maybe if the frau taught us the turtle word I would have stuck with it!

You’re the best!

I really, really loved Cronenberg's "The Fly." I still think of that when I think of really good horror films. Jeff Goldblum really made it work, and being in love with Geena Davis probably didn't hurt much.

Creepy and crawly today! I like it. The Kafka story was new to me.