One spring day about a year ago when everyone emerges to do yardwork, my next door neighbor in my country outpost in the Catskills, an elderly man who is there even less than I am, came up to the fence between us and invited me over to tour his hand-built house. As mutually intermittent weekenders here, I hadn’t really met him yet, beyond waves from our mid-mowing. But I eagerly said yes. Who doesn’t love the opportunity to peer behind the curtain of someone’s private life, witness the intimate secrets of a house and its human up close only wondered at from afar. Compared to my trailer and shed, this guy’s compound was palatial and enviable.

I got the feeling as he showed off the raw woody details of the cozy cabin rooms he constructed in the 1960s with its old skis with leather bindings and metal-railed sleds, that he was looking to see if I might be interested in taking this over someday. His grown kids have their own lives in places no where near here. This retired man has a wife who is still a practicing doctor, a neurologist no less, and they live full-time on Long Island, so making the occasional trek to the mountains only to keep up on the lawn is becoming too taxing. I wanted to do well on whatever quiz he was giving me to see (I assumed) if someday I might be into absorbing all of this. The answer had he asked was of course yes, yes if ever I could afford it. Maybe once I saw and admired this one last special thing—the centerpiece of the mantlepiece and perhaps the whole house—I’d be anointed the rightful benefactor of his handyman kingdom, the slipper to my Cinderella foot.

Introducing the Wolpertinger.

But I didn’t remember that word he used to describe this strange showpiece by the time I got back to my place, battled more thorn bushes, and then drove home for two hours to the land of unlimited internet. I had to scour the www for—I think it started with “w”— w words that had anything to do with complicated and absurdist taxidermy arrangements. I couldn’t recall the word, but I remember the creature, sort of. What my nutty neighbor showed me—with great pride and delight as the pinnacle of his house tour—was a dusty old amalgam of various smaller animals, stuffed and assembled together as if they made sense as one motley new creature collage. I believe it was a squirrel body and face, with mini antlers, and the wings and webbed feet of a duck, but I could be wrong because it seemed like a surrealistic fantasy.

When I arrived back in the suburbs, I discovered online a world of merged animals, and eventually, this Germanic concoction.

The dubious practice of constructing dead stuffed statues of multiple animals, in an article on Horror Obsessive, is known as hybrid, chimera, rogue, or anthropomorphic taxidermy. The articles cites an example of a lovely if unsettling creature, “the goat falcon fish” by artist Sarina Brewer pictured in a Fortune Small Business magazine spread from 2005, as a prime example capturing the moment this obscure art became cool. Not only is it the best kind of indie-trendy-obscure, but there’s even a vegan branch full of faux skins and facsimile.

Creatures have long been mashed up mythologically—from griffins (lion-eagles) to the hippalectryon of Ancient Greece (horse-rooster). Actual realizations of such storied creatures supposedly can be traced back to the hoaxery of P. T. Barnum and his infamous Fiji Mermaid.

From Mental Floss in an article on “7 Mythical Beasts Created With Taxidermy,”

In 1842, New Yorkers were lured into P. T. Barnum’s American Museum by a banner depicting three mermaids with shapely bare chests and long hair. Inside, the creature that greeted visitors was not a beautiful siren at all, but a grotesque half-monkey, half-fish, its face seemingly frozen in a blood-curdling scream. While Barnum’s animal mash-up was not the first “Fiji mermaid,” as he dubbed the creature, it sparked a frenzy for them in the 19th century. You can find surviving examples among the treasures of the British Museum in London, and lurking in the rafters of Ye Olde Curiosity Shop in Seattle.

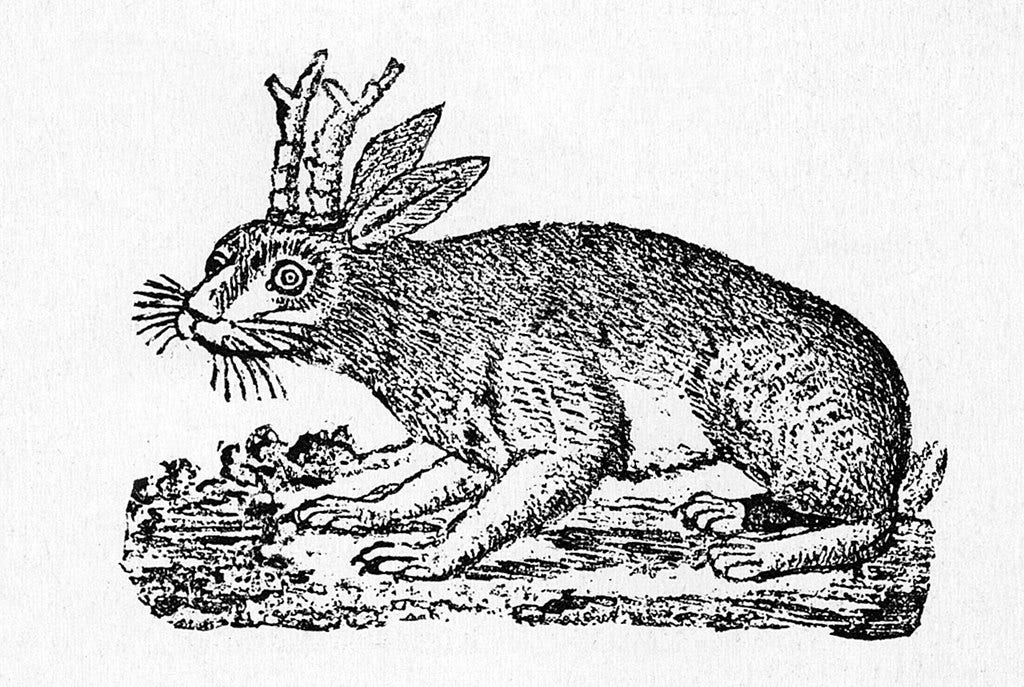

In my own travels, I recall seeing a stuffed North American “Jackalope” head hanging on the wall of a side room that was like entering a wildlife diorama at the Natural History Museum at the Clambake restaurant in Ocean Beach, Maine. The jackalope (rabbit-antelope) has a fascinating history that either dates to Wyoming 1930 or…the 17th century and confusingly blends truth with fiction:

Popular as postcard fodder in the American West, the jackalope is a portmanteau of jackrabbit and antelope. Its creation is often credited to Douglas Herrick of Wyoming, who in the 1930s returned home from hunting with a rabbit, which he put down next to a pair of deer antlers—and an idea was born. The fateful collision eventually led to the town of Douglas, Wyoming being nicknamed “Home of the Jackalope,” with jackalope hunting licenses available one day a year.

Although Herrick may have been the first to create taxidermy “proof,” the idea of a horned hare has roots that go much deeper than American folklore. The Lepus cornutus can be found in medieval manuscripts, and a rabbit with antlers can be seen among the animals in Jan Brueghel’s 17th-century “The Virgin and Child in a Painting surrounded by Fruit and Flowers.” In a 2014 article for WIRED, Matt Simon investigated the proliferation of this imagery, noting that back in the 1930s, perhaps around the same time Herrick was hunting rabbits, an American scientist found that the “horns” on some so-called jackalopes were actually tumors caused by a viral infection. Incredibly, the papillomaviruses that caused them—related to human papillomavirus, or HPV—first took root in a 300-million-year-old shared ancestor of birds, mammals, and reptiles, making truth indeed stranger than the jackalope fiction.

In other Catskills oddities, just up the road from my trailer and my cabin neighbor in the sweet mountain village of Tannersville, New York—replete with many Rip Van Winkle public images that resemble a gnome or Santa but really depict a character who fell asleep for 20 years and grew the same long white beard—is a fun and morbid shop called Bones & Stones with improbable creatures under glass like little two-headed chicks which clearly weren’t born that way.

And then, sure enough in this Mental Floss compilation on Jackalopes and Fijis and such, comes the w word that sparked my memory. A wondrous Wolpertinger similar to what I met on the mantle:

The wolpertinger is like an extreme jackalope. It has the head of a rabbit and the body of a squirrel, as well as antlers, vampiric fangs, and wings, although the recipe for the abomination is far from standardized. It’s similar to the skvader, a winged Swedish hare made in 1918 by taxidermist Rudolf Granberg.

At the German Hunting and Fishing Museum in Munich, visitors can see taxidermy “specimens” of these creatures said to be from Bavaria. These wolpertingers prowl a diorama of an alpine forest, displaying fangs, antlers, wings, duck feet, and all manner of freakish augmentations. The exact origin of the wolpertinger is unclear, although stuffed versions date to the 19th century. According to Germany’s The Local, those who want to witness these beings in the wild, supposedly born from unholy love between species, “must be an attractive, single woman” and “visit a forest in the Bavarian Alps during a full moon, accompanied by the ‘right man.’” Surely the most romantic of first date options.

Perhaps around the same time Barnum was Americanizing such things (i.e. monetizing), the Wolpertinger myth took fruition in real creatures fashioned as “local wildlife” in 1800s Germany, the birth of a tradition to mount wings and antlers on small mammals called “Wolpertinger” and “meant as a taxidermied joke.” Depending on where you are in Germany, such an oddity can also be called an Elwetritsch (Rhineland-Palatinate and Southwest Germany), says someone in a taxidermy forum on Reddit, where these German terms are bandied about, and of course there’s also a subset hybrid forum to further blur your boundaries.

But, why stop with this more recent history when you can take this all the way back to the Renaissance (late 15th/early 16th centuries) with none other than Leonardo da Everything. When I brought up my tip-of-the-tongue attempt to name my weird w-worded friend, my local literary friend Elizabeth, an editor and translator, turned me onto the exciting idea that these dead animal juxtapositions come up in some crazy passages about da Vinci in Giorgi Vasari’s classic tome The Lives of Artists. Known as a mathematician, engineer, scientist, inventor of flying machines, designer of submarines, artist, anatomist, apparently this jackalope of all trades also toyed with carcass assemblage that caused quite a rotten stink all over. There are two passages from Vasari in which da Vinci forms hybrids from different animals. First, when fabricating a model from which to paint his Medusa monster:

…He began to think what he could paint upon it, that might be able to terrify all who should come upon it, producing the same effect as once did the head of Medusa. For this purpose then, Leonardo carried to a room of his own into which no one entered save himself alone, lizards great and small, crickets, serpents, butterflies, grasshoppers, bats and other strange kinds of suchlike animals, out of the number of which, variously put together, he formed a great ugly creature, most horrible and terrifying, which emitted a poisonous breath and turned the art to flame; and he made it coming out of a dark and jagged rock, belching forth venom from its open throat, fire from its eyes, and smoke from its nostrils, in so strange a fashion that it appeared altogether a monstrous and horrible thing; and so long did he labour over making it, that the stench of the dead animals in that room was past bearing, but Leonardo did not notice it, so great was the love that he bore toward art…

Then later he’s consumed with making wings out of lizard scales and gluing them onto the back of another living lizard, as you do:

He went to Rome with Duke Guiliano de’ Medici, at the election of Pope Leo, who spent much of his time on philosophical studies, and particularly on alchemy; where, forming a paste of a certain kind of wax, as he walked he shaped animals very thin and full of wind, and, by blowing into them, made them fly through the air, but when the wind ceased they fell to the ground. On the back of a most bizarre lizard, found by the vine-dresser of the Belvedere, he fixed, with a mixture of quicksilver, wings composed of scales stripped from other lizards, which, as it walked, quivered with the motion; and having given it eyes, horns, and beard, taming it, and keeping it in a box, he made all his friends, to whom he showed it, fly for fear. He used often to have the guts of a wether completely freed of their fat and cleaned, and thus made so fine that they could have been held in the palm of the hand; and having placed a pair of blacksmith’s bellows in another room, he fixed to them one end of these, and blowing into them filled the room, which was very large, so that whoever was in it was obliged to retreat into a corner; showing how, transparent and full of wind, from taking up little space at the beginning they had come to occupy much, and likening them to virtue. He made an infinite number of such follies…

It’s a fine line between brilliance and madness. In summary, says my friend Elizabeth who read all the other pages too, “These pages also contain accounts of his more famous works, the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper, the Virgin and Child with John the Baptist and Saint Anne. It’s an interesting aspect of Vasari’s portrayal that Leonardo was an incredible genius who could do anything he tried, but who never finished anything.”

Master of none? When I bought the land upstate, drunk on the energy of taking on more than I can handle, I’d thought I’d do all the impossible things and stay forever. Tear down a ruin, turn that foundation into a pond, remove an awning and build another, upright fallen stones heavier than I in the adjacent cemetery. I thought my land would merge with all the neighboring parcels in time as folks died off, broke up, or moved away. But alas, they endure, they aren’t budging, or their prices would be too high. I can’t make that monster of a bigger strange outline and, it turns out, I’m abandoning this passion project for a larger load elsewhere with less neighbors, leaving this poor Wolpertinger and its legend behind.

I may never know: How my neighbor came to own this Wolpertinger. How old is it. If I kept waving over the fence with a smile and nodded along to more tales on subsequent cabin visits, would he have bequeathed me all this land or more importantly, its contents. So much unfinished business.

Okay, I need to write about antlers now.

Leonardo was a weird, weird dude. I'm glad he did all that weird living and thinking all those years ago so that my own weirdness can seem very tame by comparison!

I appreciate getting more info about the wily and rarely spotted jackelope, as growing up in Texas we heard and saw images about it a lot. I kinda thought it was mostly a Texas critter, but I guess not.

That goat-falcon-fish is really wonderful. I remember talking to a friend who'd gotten an editor for her NF book, then the editor decided to throw a whole other story/angle onto it, without even considering that it would then be an entirely different book. And from my perspective it would be like putting together two different things that work fine on their own, but together would hardly be able to crawl across the floor. "It'd be like a horse-fish," I said. "Yes," my friend said, "which is a *monster*!" Happy end in her case - she'd had another editor interested and was able to back up and back out, and approach that one, who took it as the animal it was meant to be.

Something I know I do in my own writing, that has gotten me into trouble, is to try and combine fiction and nonfiction (or two other different things) in ways that make sense to me in theory, but on the page... I'm going through something similar thing at the moment, having crashed with my current project. Because damnit if you ever can put together a goat-falcon-fish that actually *can* run and fly and swim (as opposed to hardly being able to crawl across the floor), you will have created the most amazing thing. And yet, it can feel (and actually be) beyond one's capacity to create a single thing that can do a single thing well. I mean, if you can just ("just" he laughs) do that, then you have a great success. But for some reason, in long form anyway, my imagination wants me to put two things together. Alas!

I would like to amend your friend's comment - "It’s a fine line between intelligence and madness" - to "It’s a fine line between *genius* and madness," and I'd imagine she'd agree. Intelligence, though not as common as we would like (as we learned recently), is not rare. Nor does it tend to sweep you away into foolish and ill-advised obsessions. Genius, however...even brilliance...well that's a different story.

I did not know all this about Leonardo. What a wild guy.

FYI, I think you're "living the life" Krista, whether it feels like it or not. Somebody would probably say the same about me, though right now it feels more like a solid ass-kicking.