I played with shades of blue in my water trilogy, now I’d like to launch a trilogy about color itself. Part 2: Green.

Green is the predominant color of my sliver of land upstate, for the majority of the year at least, until it explodes into the spectrum of autumn, drops dead brown, and then blanks out white. I much prefer the green. It’s green and not blue—I only hear water from the distant stream or watch it leaking over the top of the overfilled rain barrels. The result of the blue I can’t see is all this green I can. Now more than ever with tropical levels of rain this year. Green that breathes, and burps, and fuels my nightmares as I can’t keep up, can’t control the rude disregard of any imposed border, any attempt at discipline, choking every approved seedling with wild grasses, mugwort and thorns. Clogging my mower until it gasps and stops. I’ve scythed, chainsawed, clipped and clawed. Weeded the skin off the underside of my index fingers. The outcome is predetermined: I will never win this brambled battle.

And I love it. Nature’s not trying to kill me, but keep me alive.

In a “Nurtured by Nature” article from the American Psychological Association, studies show that the color green saves lives, or close to it:

Spending time in nature can act as a balm for our busy brains. Both correlational and experimental research have shown that interacting with nature has cognitive benefits—a topic University of Chicago psychologist Marc Berman, PhD, and his student Kathryn Schertz explored in a 2019 review. They reported, for instance, that green spaces near schools promote cognitive development in children and green views near children’s homes promote self-control behaviors. Adults assigned to public housing units in neighborhoods with more green space showed better attentional functioning than those assigned to units with less access to natural environments. And experiments have found that being exposed to natural environments improves working memory, cognitive flexibility and attentional control, while exposure to urban environments is linked to attention deficits.

Why this benefit from green space? Scientists posit three theories: the biophilia hypothesis goes back to our innate drive to be in nature since our ancestors survived in the wild. Second, the stress reduction hypothesis posits that “spending time in nature triggers a physiological response that lowers stress levels.” And the third, attention restoration theory, says that “nature replenishes one’s cognitive resources, restoring the ability to concentrate and pay attention.”

Yes, but, except for maybe the first reason, I have to ask the scientists for further hypotheses on their hypotheses. We know intuitively—because we clearly experience it—that access to nature reduces stress and cleans our cognition, but more interestingly for science is, why?

We all know Northern Europeans rank highly on the happiness scale, so I like any study that tells me about my ancestral home of Denmark with solid data linking better mental health with more green exposure—from the same article:

Other work suggests that when children get outside, it leaves a lasting impression. In a study of residents of Denmark, researchers used satellite data to assess people’s exposure to green space from birth to age 10, which they compared with longitudinal data on individual mental health outcomes. The researchers examined data from more than 900,000 residents born between 1985 and 2003. They found that children who lived in neighborhoods with more green space had a reduced risk of many psychiatric disorders later in life, including depression, mood disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders and substance use disorder. For those with the lowest levels of green space exposure during childhood, the risk of developing mental illness was 55% higher than for those who grew up with abundant green space.

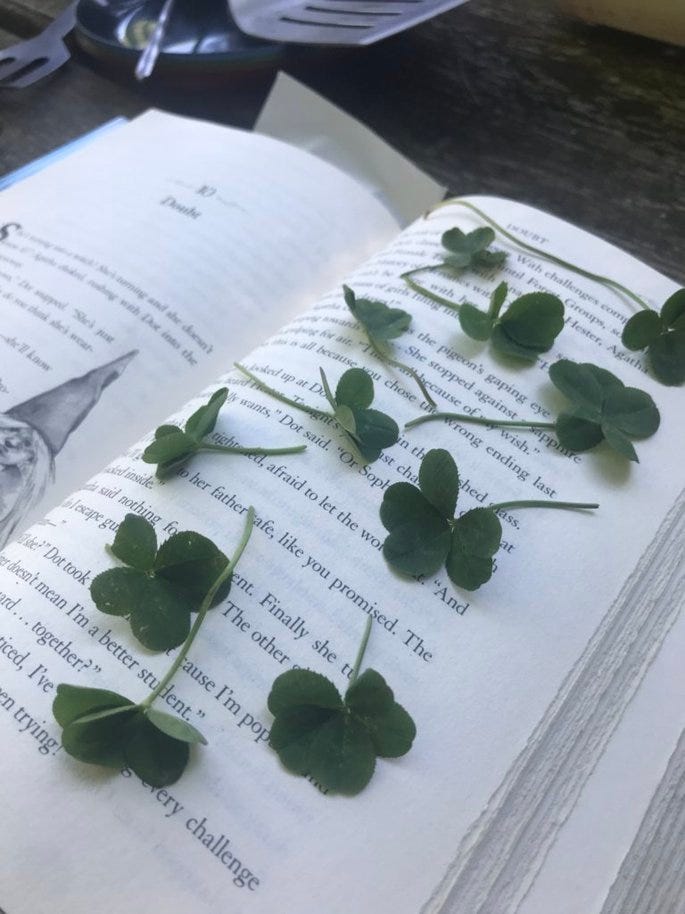

Sometimes there are simple solutions to complicated problems. I think there’s simplicity and slowness calling to us in the green space. Time to attend. Our attention is typically—at work, school, home—scattered by competing demands, messaging blipping at us from every screen. Here’s room to notice, contemplate. The air is literally cleaner here so you can take it in deeply and hold it. You might be more inclined to move your body in such a space. Push through bramble to find a moss-covered world fit for fairies. Get on hands and knees to find a four-leaf clover that leads to a weird pocket of hundreds (I’m not kidding). Or a coyote will howl here, a snake startle you—all the better to get your numb heart racing.

Green isn’t risk-free. It’s mold. Slime. Glow-in-the-dark alien skin. Tiny worms that hang from invisible threads from the sky. And the beating heart of the metaphysical movie The Fountain, where the crazy green life might just give or take your life (timestamp of the verdant oozy tree, 7 min in).

Then there’s the historic toxicity of green and this paint everyone loved so much they’d die for it. Ironically green, the color chosen by the recycling movement, contaminates recycling:

Historically, green has been a difficult color to create—it often faded, degraded, and even burned holes through canvas. In the 18th and 19th century, green wallpapers and paints contained arsenic, which off-gassed toxic fumes and led to many deaths—possibly including Napoleon Bonaparte’s in 1821. Emerald green, also known as Paris green, was incredibly toxic and was at one point used to kill rats in Parisian sewers.

Many of the super toxic green pigments have been banned, but even the modern pigments are still environmentally unsafe. As Alex Rawsthorn of the NYTimes reports, Pigment 7, one of the most common shades of green used in plastic and paper, contains chlorine, which can cause cancer and birth defects. Pigment 36 contains potentially hazardous bromide atoms as well as chlorine, and Pigment Green 50, which is inorganic, contains a “noxious cocktail of cobalt, titanium, nickel and zinc oxide.” So having direct contact with the pigments is unsafe, and on top of that, the pigments make green plastics and paper difficult to recycle or compost, because they contaminate everything else. If what Braungart says is true, then perhaps it’s time to choose new team colors.

I have a book in my brain that I’ve been working on (mentally) since I owned a bar in Brooklyn in an old tenement that I exposed for the original tin-ceilinged space it was once—perhaps a bar!—from 1890. In my novel about this space there will be a literal “pick your poison” drink menu, bowls of lead paint chips to nibble on, and seething walls of Paris Green. My grandfather used to tell me how he used to eat the paint chips he flaked off his house growing up—how sweet they tasted.

It occurs to me as I write this that the great riffs on One Word that

produces might have a green episode in his archive, and sure enough, he captures exactly this paradox between fresh and rotten, healthy and toxic that this color encapsulates—from teeming clover fields to a father on his deathbed. From his post on Green:Passive, gentle chlorophyll and the slimy excretions of toads. When I close my eyes and think of green, I see fields of fresh clover brighter than the sun above it. Alive and thriving. I also see my father on his deathbed, the sting of alcohol wipes, and the pungent and nasally green that hung in the bedroom those last few months.

The root of green, in over a dozen languages, means to grow. But in which direction do I grow? Up into the heavens, like fresh spring leaves? Or down into the dark, damp earth?

Green’s unique attribute is its spectrum. Up and down. Sickness and health. Life and death. It rubs against an unspeakable element of earthly existence. When the summer approaches, and the sun spreads its warm breath across the land, before the daffodils and the blue jays, we experience bursts of green. But in the shadows, where the sun cannot reach, mold overtakes felled trees and verdant decay spreads like a cancer.

Put another way, green has something to do with attention. Just like the sun, what I focus on will grow. What I turn away from will rot. Green is a paradox.

Green is not my favorite color—I won’t even wear it, let alone paint my real room with it, but it is what I gravitate to most in nature. Beach or mountains? a typical dating app prompt. For me it’s definitely mountains. I want access to some body of blue to float in as nearby as possible, but it’s the green that chlorophylls me. The work and the wild, both bitter and sweet.

In the contest between what’s better for you, green (land) or blue (water), one study demonstrates that blue might edge out on measured benefits, or it’s a pretty close tie.

Anyway, this isn’t a contest.

It’s a fight for your life.

[Next stop: red.]

Very cool to see you also explore the many characteristics, feelings, and mysteries of Green. It also brought a smile to my face coming back from a camping trip finding out anyone would reference my work on the subject. Thanks so much and great work!

I'm with you, mountains over beaches any day. Wish I had your green. Upstate New York is calling me.