I’ve managed to avoid donning any virtual reality headsets in my life until I attended a Maker Fair recently in this complex of amazing old brick factories at the Garner Arts Center in Garnerville, NY. One dark room from installation production duo Trouble called “You Are Not Here” intending to “extend their maze work into the metaverse” had a lightshow projected on the walls and tape on the floor. You could wander the actual room and navigate their taped path of a maze or you could enjoy one of two VR headsets to try mazing in your brain instead. I walked the real maze and bypassed dead ends by jumping over tape lines when no one noticed.

No one noticed because they were setting up my boyfriend and his son in dual-goggle experiences. The five-year-old was outfitted with his new world and dad about four feet away with his. They were supposedly now wandering the same maze I was. They were talking separately and unheard to each other, narrating their journeys at the same time, both telling the other they were looking for them. Their hands held controls that pawed at the air between them. It made me uncomfortable just to watch this scene, and I had to eventually nudge the bigger guy who was oblivious to the line forming of those waiting to do the same.

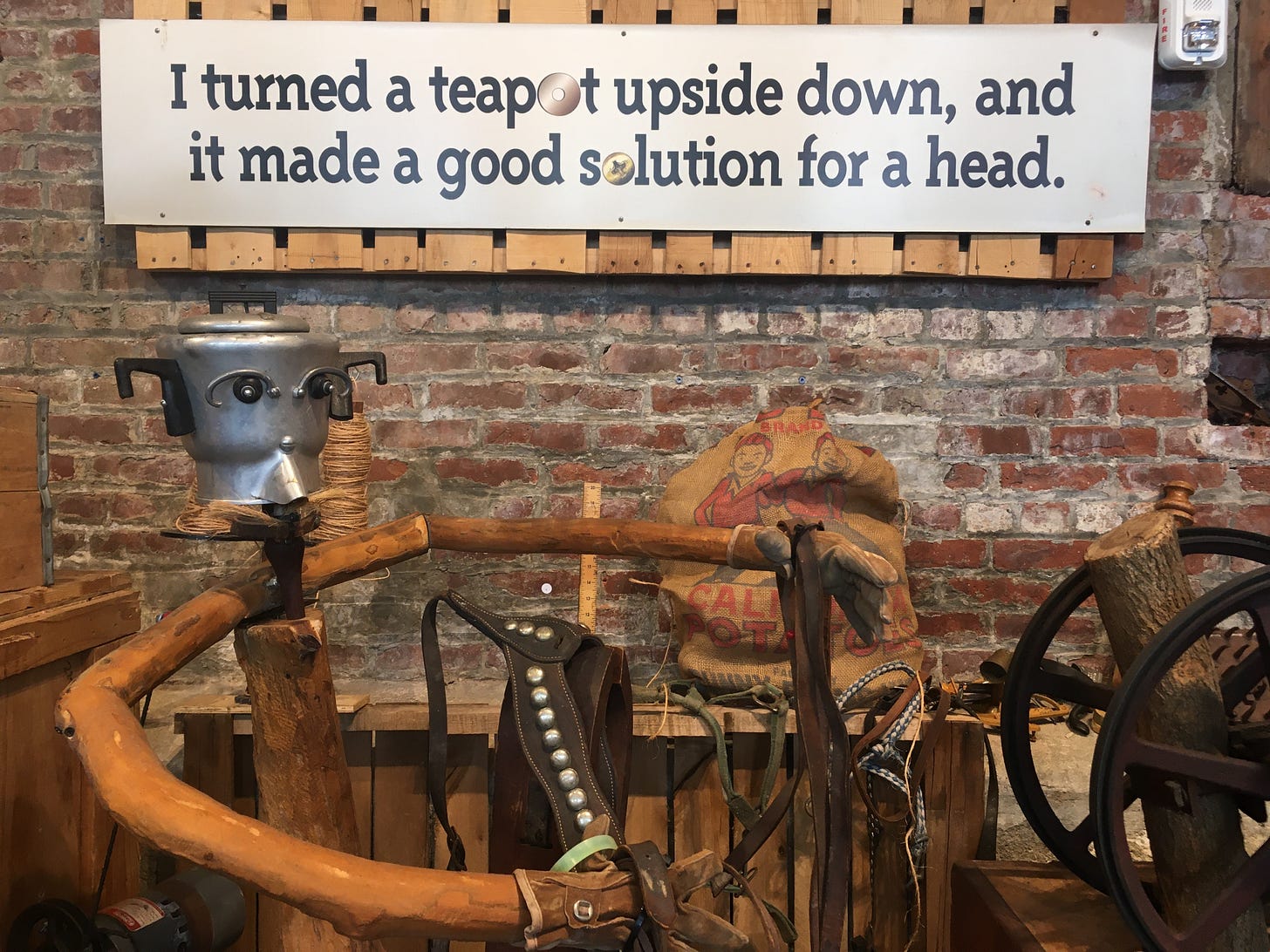

Determined to be a good sport despite zero interest, I decided to try it too. For what felt like way too long but was probably only seconds, I fumbled with the controls to navigate the metaverse maze but I couldn’t figure it out and felt lost and clumsy; the floor was wonky; the structure was so insubstantial and floaty. This wasn’t like the immersive world tour at Epcot where it truly felt like we were flying over fields of antelope with a breeze puffing in our faces, a floral smell wafting through, all fresh and liberating. There weren’t goggles over our eyes then so our family could experience this together, side by side in our padded lounge chairs, smiling, sniffing. This sealed off room inside of a room, in my goggles in my brain, was dizzying, constricting, disorientating and came with no apparent benefit beyond isolation and awkwardness. I felt dizzy, nauseous. I needed to reemerge, rip off the gear, and run back into rain immediately, or at least to some other warehouse exhibit that had some tangible touchable things in it, like the eccentric sometimes-spinning sculptures of Steve Gerberich:

Kids love to make themselves dizzy. I remember twirling in my childhood living room that no one ever set foot in, and nearly falling (to my imminent death or at least traumatic brain injury?) into the brim of the marble fireplace—no matter. Then there was the tilted metal disk at the park that spun fast and askew when kids got it going and you held onto its edge rail for dear life trying not to fly off centrifugal. It was covered with these berries from the hackberry tree, which would roll and scatter with the bodies. I remember the sound of that playground equipment, the smell of the berries and metal, the ever-satisfying nausea. And then revisiting it many years later and not even being able to look at without feeling sick to my stomach.

At what point does childhood sought-after dizziness become the awful queasiness of adulthood? As I grew, I would get carsick on our family road trips, so I remember my dad having to pull over in East WhatTF to let Krista get out and breathe for a bit on solid ground. Now I definitely don’t want to do things, like swinging and spinning—forget a cartwheel—that used to be fine, even fun. I adore roller coasters, especially rickety wooden ones, but don’t you dare put me on one with smooth rails that goes in vertical loops unless you want my vomit to fly back in your face. Science doesn’t really have an answer for why we grow out of this interest in dizziness, beyond that kids have less expectations of which way the world goes and are less psychologically shocked by radical shifts. That said, we supposedly still have the potential of great plasticity at any age and with practice can get comfortable with anything, including those things we used to do. Mad props to any adult cartwheelers out there! I’ve discovered virtual reality nausea is a real thing and not just my personal problem, which also apparently just requires getting used to. It’s a newbie problem that the industry is trying to navigate. Well, too bad—I don’t want to grow accustomed to this, so I’m choosing to take my cybersickness as a warning sign to back off.

Sometimes I get the same feeling that I do when I’m reading in the backseat on windy roads when I spend too long hunched over a phone scrolling through a lot of nothing-much, or just even doing my job, which requires Infinite Computer just to keep up on emails. And then in this middle-age phase of nonstop financial hustle I’m in (cue the perimenopausal nausea for good measure), I get to go home and log in to work all my cyber side gigs until I croak.

Does this new form of cyborg hybrid we’ve become (human irrevocably attached to device—a device in whichever form I believe is the actual leader we now report to and follow its every demand as long as it speaks WWW), get sick from this lifestyle? I think so. We haven’t evolved yet into the ideal form for this type of machine-attachment, and until then (and maybe more dramatically after) we are twisted, headachey, eye-glazed like donuts. When we do detach and re-enter a place with sun or natural air or people clumped in chatting formations, we are awkward, pale, weak, shy, dope sick.

This great history on How the Personal Computer Broke the Human Body in Vice Magazine, also importantly refers to broken spirits. As early as the 1980s there were studies like this:

What the computer did was make the work so routine, so boring, so mindless, clerical workers had to physically exert themselves to be able to focus on what they were even doing. This transition, from work being about the application of knowledge to work being about the application of attention, turned out to have profound physical and psychological impact on the clerical workers themselves.

Zuboff was able to track the extent of this toll by asking the clerical workers to draw pictures of themselves at work before and after the computer. These images reveal themselves, embodying a kind of juvenile terror in their simple lines and stark contrasts. The workers depicted themselves as happy in the times before the computer, and frequently in the company of others.

What the computer brings to them is a kind of desolation: a worker who has become nothing more than the back of her head; hair, ripped from the scalp; a deep sense of being alone. One of the most detailed drawings is accompanied by the caption: “no talking, no looking, no walking. I have a cork in my mouth, blinders for my eyes, chains on my arms. With the radiation I’ve lost my hair. The only way you can make your production goals is give up your freedom.” The side of the desk is marked by the ascending arrow of a productivity chart. Another image depicts the worker in the striped uniform of a convict. A phone ring ring rings on the desk and a flower in a vase droops beside the computer.

What to do? Well, if you’re stuck in that office chair for eight hours, might as well exercise with a smile. Here’s Denise Austin in 1988 with her “Tone up the Terminals” pamphlet, thrilled to share her bendy anecdote to despair and paralysis.

My friend Dana and I, circa 1999 at our job in the early DotCom heyday in NYC when we wrote book blurbs and IMed each other giggling just few feet apart all the lifelong day, had her mom calling us from home every 20 minutes to remind us to look away from the screen. The rule of 20s will save your sight: Look for 20 seconds 20 feet into the distance every 20 minutes.

Extend this to 2023 and beyond, where we’re 40+ years into this grand experiment and only getting deeper. If you’re not at your standing desk yet doing lunges and looking away every 20, this is the future: By 2100, according to a 3D render of a human “Anna” created by an office furniture store in the UK called Furniture@Work (who has since removed the post), if we continue to do this extreme virtual work from home, we could be pear-shaped hunchbacks, with claws, bloated limbs, and red eyes. (I would argue offices are way unhealthier and constricting than working from home where you can jump around freely, but they are selling corporate furniture so you can assume their bias in this unscientific render). In any case, Anna, meet Michael, created by Online.Casino.ca to reveal the ugly truths of the gaming body by 2040. Michael, a video game addict, which by now is recognized by the World Health Organization as a psychological disorder, suffers an indent in skull, bald patches, hairy ears, eczema, blisters on fingertips, varicose veins, trigger finger, plus brand name problems like Playstation thumb, Nintendo arthritis. He has much in common with Anna: terrible posture, rounded shoulders, eye strain, obesity, pale skin, carpal tunnel syndrome, swollen ankles. Meant to be? Could they fall in love?

Probably not, because they are too wrapped in the bubble of their own metaverses of course. The screen addictions run so deep now that our better angels seem to have gone silent, replaced by the urges that scream: Never turn it off, never turn away, climb more fully into the machine, go deeper, live there permanently, sleep and eat and use the restroom with it! Let it fill any moment you might spend waiting or not knowing what to do with your fidgety hands/mind, like an old school cigarette. Scroll until the pads of your fingers burn and you have no prints.

Should you become brain-dented like gamer Michael, you’re not going to have the real-world opportunity to bump up against any Annas, catch that she is, so now maybe you require a virtual girlfriend because you’ve become too f’ugly and antisocial for a real one. Apparently there’s a waitlist 15,000 people long for a virtual chatbot girlfriend CarynAI—notice that’s just an AI Girlfriend. I don’t think straight women (yet?) want an AI Boyfriend, nor do I picture lesbians caring about an AI Girlfriend, so perhaps this is just a straight male interest? To employ some gender stereotypes, which I often find prove to be true, maybe men don’t need to go so emotionally deep conversationally. So maybe just the digital looks of the virtual lady and her ability to perform pleasing enough and responsiveness enough without ever probing or challenging her suitor too much, is just right.

I already feel like I’m stuck in my head and can’t properly connect with people. As soon as I was conscious enough to think it (let alone old enough to start reading the dread existential philosophers), I knew we have our own virtual realities we’re trapped in and can never really be known or know anyone else, that we’re pawing at empty air between us, navigating life-mazes that are possibly illusions. Our atoms never really touch between our force fields to begin with. There is no real contact. So why if we’re already so separate, would we need even more layers between us, more distance to buffer us from really touching, really smelling, really seeing the thing itself, whatever that is. Why further forgo reality when it’s already so precarious?

Not being heard, not being seen is an ongoing problem of mine. I often feel like I’m speaking loudly, too loudly, but people can’t hear me—as if I’m in a nightmare muffled in gauze. People that I think should recognize me, don’t. I once participated as a test group in a Discord platform game where we were meant to be in a sort of a Clue whodunit, going from room to room to try to track down the murderer. The sound on my computer wasn’t working and I spent the whole game silenced, feeling like a creepy ghost who entered rooms and couldn’t answer anyone. Much like a Zoom gone awry, I had to text everyone, “audio issues.” I was so uncomfortable and useless for the duration of the game but didn’t want to just bail. Which reminds of the time I did have to bail, when years back I smoked pot laced with something too much for me in the city and had to jump off the subway before my destination to retreat home paranoid instead of going to the concert with friends. I’ve never wanted that escape-veil of drugs the same way I can’t tolerate the idea of VR, the disorientation, a loss of control, not knowing how I’m being seen or who’s looking at me as I flail around a room talking to myself. Nope.

I told my boyfriend, who does Discord meetups for his crypto hobby and loves video gaming with his kid, if he ever bought a headset, I’d be out. We already struggle with our vastly different appetites for and attitudes about screen time and allowance for what’s acceptable at what age. Luckily he agreed he too has his limits on the VR front.

The new Apple Vision Pro headset costs $3,500, overlaying everything in your world of vision with computer apps, so you’re not closed off, just further layered, software ever the more integrated. It even recreates your face and gestures in Facetime so people (at least the 2D ones if not the poor real people around you) get to see you without the stupid goggles. Instead of this fancy ski mask, how about spending that money on a shed on a trailer (that can someday be outfitted as a tiny house if you buy another shed for your lawn mower and wheelbarrow) that you can decorate with bits you rescued from the collapsing ruin of a giant boarding house, for example. When you set it on a gravel patch, you can sell the trailer it came on for a thousand or so and fund the next shed. And so on…

This is the portal through which I reenter my favorite version of the real world. I go to the Catskills most weekends, or as often as possible, for nature-immersion in the form of hardcore yard work, shed building-decorating, going medieval with stone dragging and chiseling, reinhabiting my brain and body. At first it was a remedy for the Zoom screens of the pandemic, a patch of green dream, and now it’s just necessary ongoing to survive full-time in an office plus the required screen hours of all the gigs, including this one of writing these newsletters. There’s a problem that writing (my love language?) requires ever more computer-attachment so I often struggle with some aversion to my own medium, arguably my biggest skill and life-ambition, that comes in the wrong package. I think about the possibility of dictating my writing as I weed the mean mugworts, but the words don’t flow the same way for me out loud as they do when my hands are moving across keys, filling the virtual page. It’s like ten tiny brains in my fingertips require the “ancient QWERTY” as

puts it, to actually form coherent sentences. He was referring to an actual typewriter, which I’m not luddite enough to tolerate when there’s no dragging and deleting, but I do love that clicketyclack, the feel of paper, the lost smell of ink.I undo the damages of the desk in the country, bend my body back from the ass-sitting hunch and awake the benumbed brain. Report to a different god than the rectangle before me in the mountain mist in the distance. If I’m sore later, scratched and muddy and crawling with ticks, I know I’ve succeeded. I mow my lawn round and round in tightening concentric rings and might even contemplate a cartwheel.

I am here.

I loved that you called attention to this Vice quote: "application of knowledge to work being about the application of attention"

This nails it! In those increasingly rote roles, performed throughout the world by hundreds of millions of people, your job is NOT to think. It is to pay attention.

Your "job" on social media, from the platform's perspective, is also to pay attention. It doesn't matter if you're happy, outraged, depressed..... just pay attention, no matter the negative implication.

(also, thank you so much for the mention! I hope some of your readers gain value from an additional, complimentary perspective)

As a semi-aside, the body can only take so much of this (Michael and Anna). Over time pain becomes a real issue and there'll be no thinking/abstracting your way through that. Have spent some years fighting through some truly painful and at times semi-crippling tendonitis from the body positions all this technology has us assume. It's feels kind of amazing that it's gone now. How to keep it away? Yeah, respect the body and exercise. Also I'm just like you with the typing and I think it's because the body's involved (and with it a different part of the mind).