Death Valley hit 125 degrees this week.

As its name conjures, Death Valley, CA—hottest and driest spot in North America—on a good day isn’t really where you want to be hanging out too long, let alone when it hits warming-oven temperatures. And for me it conjures yet another of those over-the-top, fictional-sounding moments from my youth that actually happened.

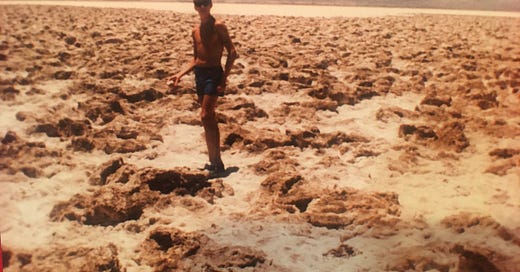

When I was maybe 10-11 years old, we took a family trip out west through various canyons and state parks from Colorado to California. While other families sat on donkeys to traverse the trail up and down the Grand Canyon, mine hoofed it. I just vaguely remember the dry dust kicking up as the donkey train passed us and how my father (and even us kids, but definitely not my mom) might have scoffed at those lazy folks while we proudly hiked—without nearly enough water. We did have water but in such circumstances it’s rarely enough and you have to pregame your water intake too which I’m pretty sure we did not. We did the hike fine, up and down this giant scar in the earth for however many hours. But later in the rental car, as my dad drove on toward the ominous sounding Death Valley, which I see now on Google Maps is a 6.5 hour route at least, I started to feel sick. He had to pull over a few times for me to retch in the brush along the shoulder. I believe with my existing carsickness tendency, this was considered pretty standard for our road trips and wasn’t just the child abuse it might sound like. Then we arrived in the Valley and while my brother and father stood out in the moon-craggy expanse, my mom and I sweated it out in the car, unable or uninterested in enjoying this surreal moment with them. Only after this, as we continued driving wherever else we were heading, did my dad realize it was time to look for some sort of a health clinic. I don’t think it occurred to anyone that I might have had heat stroke until the doctor told us, and prescribed unlimited amounts of Gatorade from the gas station pronto.

Now Gatorade forever has that connotation to me, connecting donkey dust and Death Valley with that specific fake juice taste and unnatural color (I believe I chose orange?), so I hate the stuff, but also appreciate its worth as emergency medicine, if not always my father for being so extreme/oblivious.

I learned how quickly heat stroke can actually kill a person, and how lucky I am to be alive, when it suddenly took the life of a friend and my favorite writer Matthew Power in Uganda in 2014. Much like the young rising-star journalist Kim Wall who got murdered interviewing my least favorite Danish submarinist, the worst story Matt was associated with was the one he never got to write—the story that killed him.

Matt, who was already well-established as an incredibly gifted long-form, immersive essayist in his 20s, traveled the globe to cover for the likes of Harper’s, National Geographic, Slate, and GQ stories such as the murder of a Costa Rican protector of sea turtles, anarchists floating down the Mississippi in a raft of their making, or the Filipino garbage pile local villagers survived off like parasites. When we overlapped and briefly dated in the city, I was so honored that he spoke as special guest to my Creative Writing 101 international students at NYU, and came to my fiction reading at KGB, transporting me home after on his motorcycle over the Williamsburg Bridge. Gripping onto him over the East River and looking back at the Manhattan skyline glittering behind us felt like the height of living, but it was also one of those moments where I’m so aware of our human fragility, and the delicacy of relationships, ours which of course ended soon after when Matt wandered off to write another epic story far away and, surprisingly for someone so endlessly nomadic, got married.

Many years after I couldn’t keep him, Matt at the age of 39 on assignment with Men’s Journal traveled to Africa to walk a leg of the world’s longest river, The Nile, for a week with a British adventurist exploring the full 4,000 miles by foot for a year to be televised of course. I saw disturbing footage from the journey of Levison Wood and team that shows how quickly Matt was lost from hyperthermia within two hours of feeling unwell, with no way to get a rescue helicopter out to save him in time and any available water not enough to cool him. This article in the Daily Mail reveals in painful detail how traumatic it all was, and how powerless everyone around him to help.

Florio [the photographer on the trip] told MailOnline that the plan was to walk for about nine miles, then hitch a ride to the next camp and wait for Mr. Wood and his guide, Boston Beka, to complete the rest.

He said: “Once we got into the game reserve, the terrain was really difficult. We were walking in a dirt swamp and the ground was very uneven. There was elephant grass 6ft to 10ft high.

“I felt claustrophobic and it was blisteringly hot and you couldn’t see anything. There was a point when we thought we were going to cross a river where we could cool off but it was completely dry.”

The temperature that day was up to 45C, or 113F. Florio said that his and Mr. Power’s feet were blistering badly because they were sweating so much.

After about five miles Mr. Power said he needed to sit down, and Florio was grateful for the break. Mr. Power said he did not feel well but Beke said that they should press on.

Better to find some shade as it was lunch time, when the heat was at its worst, he said.

Florio said: “We cleared the swamp and it was at that point we realised something wasn’t right with Matt.

“We got him to sit down. He was throwing up. He was becoming disorientated and we tried to get some water into him. He was delirious very, very quickly.

“I kept saying to him ‘keep breathing,’ but I couldn’t tell if he was hearing me. It was quite frightening to see how quickly someone can shut down in that situation.”

Beka and one of the rangers left to find water.

Those who stayed rung out their bandanas to give Mr. Power some water and used up the rest of their meagre supplies.

They took off Mr. Power’s clothes to try and cool him down but they could not stop him going into hyperthermia, the opposite of hypothermia.

When your body’s internal temperature gets above 39C [102.2F], it effectively starts to shut down.

Once the process begins you have about 30 minutes to cool down before you slip into a coma, and eventually death.

We know the body needs to stay around 98.6 degrees—hit a handful of degrees higher or lower and things get disastrous fast. But how this relates to external temperature and what’s dangerous for humans is a little less straight forward.

An article in Grist explains along with this informative video below:

There’s a temperature threshold beyond which the human body simply can’t survive—one that some parts of the world are increasingly starting to cross. It’s a “wet bulb temperature” of 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35 degrees C).

This doesn’t mean a mere 95 degrees will kill us; actually less than that could. “Wet bulb” is the more important measure we need, combining heat and humidity. Turns out dry air, as in Death Valley, is much better in terms of our survivability than wet. In dry air, our sweat can quickly cool us down as it evaporates vs. sweat having little effect when the air is too moist and sweat just stays on you. Wet bulb temperature is the temperature we experience after sweat cools us off. So a 120+ day in Death Valley might really measure only 77 degrees in wet bulb, while other slightly “cooler” parts of the world might measure much higher due to humidity. Our secret sauce of sweat won’t work in these unbearably hot-plus-humid climates, which are overall on the rise in the world.

When the wet bulb temperature gets above 95 degrees F, our bodies lose their ability to cool down, and the consequences can be deadly. Until recently, scientists didn’t think we’d cross that threshold outside of doomsday climate change scenarios. But a 2020 study looking at detailed weather records around the world found we’ve already crossed the threshold at least 14 times in the last 40 years.

So my odds were way better in Death Valley in the 1980s than they were for Matt in Northern Uganda in 2014 or for the earth in general these days.

While the hottest day recorded in Death Valley was actually 134 degrees in 1913, that doesn’t account for how it’s now consistently hotter, year after year. We witness regularly the new extremes at play everywhere. Hurricanes, cyclones, forest fires, draught, flooding, torrential rain, even blizzards, are increasingly dramatic—beyond the point where my mom is allowed to say these are normal, cyclical fluctuations or “acts of God.” If she wants to talk about God, it can be more along the lines of what Jack Handy would say in his SNL “Deep Thoughts” snippets:

“It’s raining because God is crying—probably because of something you did.”

New York is becoming so tropical my girls needn’t miss their annual trips to Florida. The most pressing problem in my immediate world has lately been installing a new roof on my garage before my several garage renters wash away.

The first week of July came with the news that it was the hottest planetary week on record, after a hottest whole month of June. I’m no meteorologist but the sky is falling. Or as the World Meteorological Organization wrote on July 10 (with my emphasis):

The world just had the hottest week on record, according to preliminary data. It follows the hottest June on record, with unprecedented sea surface temperatures and record low Antarctic sea ice extent.

The record-breaking temperatures on land and in the ocean have potentially devastating impacts on ecosystems and the environment. They highlight the far-reaching changes taking place in Earth’s system as a result of human-induced climate change.

“The exceptional warmth in June and at the start of July occurred at the onset of the development of El Niño, which is expected to further fuel the heat both on land and in the oceans and lead to more extreme temperatures and marine heatwaves,” said Prof. Christopher Hewitt, WMO Director of Climate Services.

“We are in uncharted territory and we can expect more records to fall as El Niño develops further and these impacts will extend into 2024,” he said. “This is worrying news for the planet,” he said.

If you enjoy feeling alarmed spurned by effective visuals, drag the global temperature differential slider in this NASA.gov animation from 1884 to 2020 to see how the good blue earth has morphed to yellow and red. And, yes, because of something we did. “Key Takeaway,” says NASA, (bolding again my own):

Earth’s global average surface temperature in 2020 statistically tied with 2016 as the hottest year on record, continuing a long-term warming trend due to human activities.

Or there’s more graphs here on NOAA.gov, with fun facts like,

the 10 warmest years in the historical record have all occurred since 2010.

Basically, you could fry an egg on my climate anxiety.

From a local government standpoint, since that’s my day job, we can’t even begin to address helping people in the way we need to stave off the kind of problems that will just keep increasing. No amount of drainage clearing over the aptly named Troublesome Brook is going to be able to compete with the levels of rain we’re facing. Even from a Federal perspective, they could declare us a FEMA disaster zone every storm and the millions we have to fight for years to receive would never be enough to complete the kind of massive infrastructure overhaul every single community in the country (let alone earth) may need soon—whether to stop fires, the air quality problems from fires, too much water in some places, draught in others, cataclysmic storms, rising sea water engulfing the coasts, rising temperatures driving us north. We will soon see climate refugees, water scarcity, widening food deserts.

I receive a regular eblast from the farm I used to get my CSA box from weekly and—here’s something most people don’t think about when it rains too much—they said many crops were wiped out for the rest of the year from the massive flooding in the Northeast in recent weeks. All that time, energy and farmer investment to get from seedlings to plants, and good food—gone.

So the sky is falling—100-year storms, 1,000-year storms, a planet too hot to sweat— and what are we going to do about it?

Writes HEATED, dedicated to this topic,

"What can I do?" Anything. The battle for a livable future is a battle against fossil fuels. Right now, it's all hands on deck.

I know the answer isn’t running the space heater I have near my desk when the A/C at the office is so unbelievably cold. Note to self: pack a sweater. I just had a whole conversation with my colleague who was talking me through the various flood mitigation efforts the Department of Public Works is trying to keep up with, bit by bit only ever able to bandaid each most-pressing problem. I appreciate in the statements from the .Gov experts above that they all make a point of mentioning these are human-made issues, and only then I believe it’s possible that we can imagine a new world where us silly yet smart humans might be able to fix it. The DPW guy, who is out there reacting to these daily impacts, is still denying the science! It’s cyclical, he said. I showed him the charts referenced above, peaking only in recent years and like we’ve never seen. It’s China, he said. I asked him who buys the products from China? He basically said, it is what it is, so be it. He’s retiring and moving south soon so…shrug. Always the contrarian, I suggested he go further north! But truly, I think everyone will be seeking the balmy clime of Canada before you know it. And doesn’t he have grandkids’ futures to worry about while he retires?

I refuse to be the deer hit by the car that just slumps off to die alone in the woods. I’m fighting every little degree with everything I got, which isn’t much in the large-scale, but I’ve invested every last penny in the off-gassing journey I’ve charted in full here while I pretty much spend zero elsewhere. Next stop, now that I have my new flood-proof roofing, the final step toward net-zero is coming with solar soon.

By sharing the science and my alarm and even my (true!) tall tales, I don’t mean to scare my daughters into paralysis but rather advocacy and action. If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. My dad was a great environmentalist, and he preserved many acres of land in my birth town, but he was also, confusingly, a climate change denier because of the dictate of his politics. I’m pretty sure if he were still alive that would only be heightened now in this more divisive world. And if I were a kid now and we took that detour through a much hotter Death Valley, I’d probably be dead.

We children of the ‘70s were raised under a certain amount of benign neglect that passed for parenting at that time. Benign neglect doesn’t fly anymore—not in terms of parenting and definitely not for our planet.

If Matt were alive today, I’m sure he’d be writing something stirring about a remote island tribe somewhere in the path of rising sea levels, suffering the wrath of global warming on a gritty, everyday level where they can’t get enough fish to eat or wood to build from, and his words could have moved us privileged readers to do more. Something—anything at all.

And, please, drink lots of water.

Very good work weaving the personal narrative with a bigger picture story.

I grew up in the south, so high humidity and high temperatures are still fairly normal to me, but there have been days in the last couple of years where even I felt that intensely hot sun beating down on my skin, and realized the game had changed.

So sorry to hear about your friend's demise, a horrible way to go. The southern parts of Canada, where most of us live, are not immune to climate change either.