The word of the week was “submersible” and we all know the tragic outcome. Awaiting the inevitable news of the demise of the Titan five—apparently lost at deep sea post-implosion only partway through their journey to the North Atlantic Titanic wreckage—has the world contemplating many things: the sort of arrogance you can buy, willful recklessness, the woefully unregulated industry of adventure tourism, uncertified shoddy structures ill-equipped for their mission, the dubiousness of paying a fortune to ogle a sunken graveyard.

Before Submersible Week, an office colleague who loyally reads my newsletters and was enjoying my recent water-fixated series, asked if there would be another wet post, I said no. But this news has me compelled to make it a trilogy.

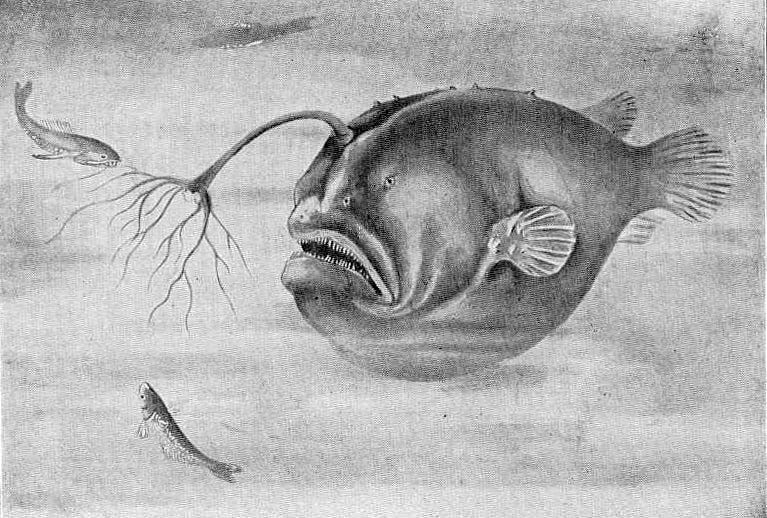

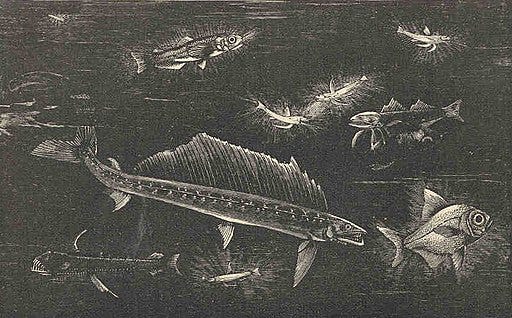

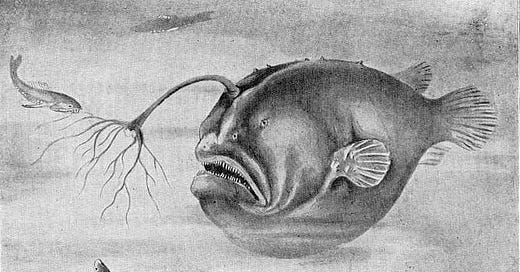

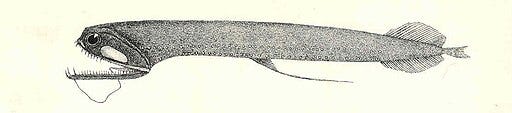

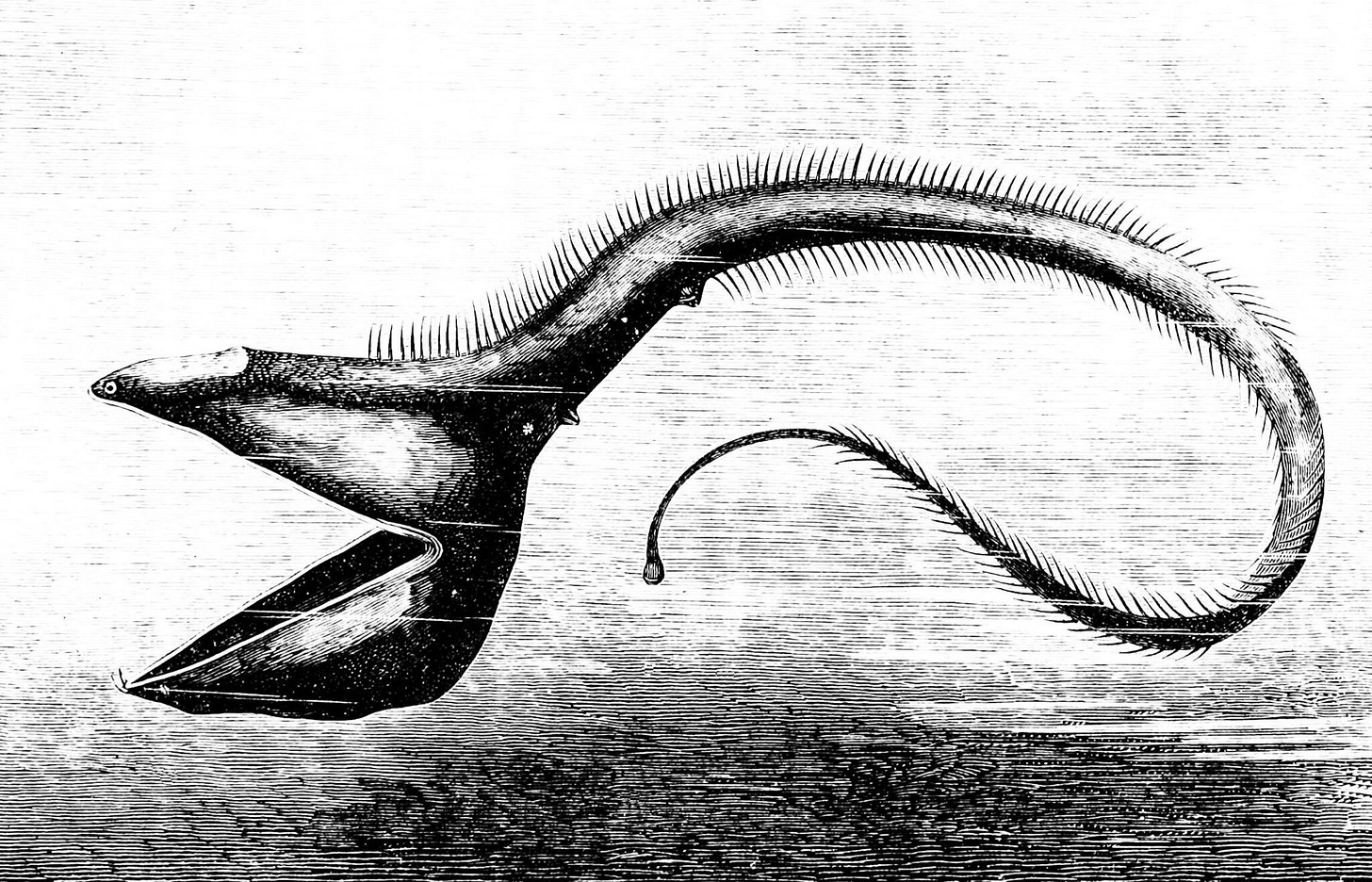

First, Out of My Blue Mind explored our magnetism to at least the edge of water, then Waterlogged, our human compulsion to toss messages into it, and now comes the dive where you launch yourself deep, if you dare. It’s not pretty, nor cheap. I’ll intersperse my extreme adventure into the dark unknown with creepy undersea fish illustrations from the late 1800s/early 1900s to set the mood, and end it with, shall we say, my “favorite” murder. Which means it’s one of the worst stories I’ve ever heard, one that—to borrow another word much bandied about this week—really “haunts” me.

If you haven’t already imagined the claustrophobia of inhabiting a carbon fiber container for a $250,000-per-ticket half-day trip, here’s a tour of the tiny insufficient private sub built by OceanGate. Not all subs are the same, we learned first: submersible is not to be confused with submarine, as the first is only partially powered for short trips, while the latter is fully functional for long journeys on its own. What would you get for this money? Reportedly there were numerous unheeded warnings about the viability of this vessel but I don’t see much grounds for any mourning families suing when the explorers signed waivers that used the word “death” at least three times. I was fascinated to learn that there was a toilet with a privacy curtain and privacy music should you need to go; just that one mere portal window for the five guys to puzzle piece themselves together to peer through; and cold crowded floor space for them to sit on for the 8-10 hours of their journey down, around the Titanic, and more slowly back up. At least with the news of implosion, we can assume they didn’t suffer (imagine trying not to greedily gulp for the last remaining air) but experienced a sudden demise. When that outcome was still pending, and there was maybe, said an expert, a 1-2% chance of the Hollywood ending that had them emerging in the final seconds before the oxygen ran out, I pictured this crew of older dudes (and one teen), time ticking more urgently each moment in the dark depths. Who would find the inner strength to behave like a god? Who might turn into a monster? At what point did the adrenaline giddiness of the journey turn into sickening terror? Sure I wanted them to be recovered alive, but definitely not celebrated as heroes. Now, sadly, there’s nothing to show of any of it, beyond some torn Titan parts.

Many more people have successfully gone to space than the small handful who have gotten this far into the ocean. Many astrophysicists and marine biologists seem to agree that the ocean is way scarier in this interesting informal survey of experts on Inverse.com:

One day, you’ll be at the aquarium trying to appreciate the Hawksbill sea turtle or a family of otters, and it’ll suddenly sink in: Everything in this place wants to kill you. The only thing separating you from their fishy clutches is a tiny glass screen through which they actively plot your demise.

The ocean is a cruel and beautiful arena of death, but it isn’t the only place that puts our mortality into perspective. Dying in the cold, unfeeling vacuum of space seems like it’d be very lonely—but still more dignified than having your remains eaten by deep-sea dwellers in the Mariana Trench.

Basically you’ve got just physics in space, and biology plus physics in the ocean. It’s the biology part that wants to eat you, and that weird human biology part that leads us into these messes in the first place.

The ocean proves yet again that it’s far more dangerous and uncharted territory, as any random billionaire seems to own a rocket company now that is privatizing space flights easy-peasy. Of SpaceX (Elon Musk), Blue Origins (Jeff Bezos), and Virgin Galactic (Richard Branson), Blue Origins has gotten farthest into ticketed passenger travel with six flights so far. The first had open bidding for its fourth seat which went for, oh, $28M. The winning crypto entrepreneur had a “scheduling conflict” (can you even imagine) and passed his spot along to the 18-year-old son of the CEO of an investment firm. So you had the youngest in space along with the oldest, a woman, Wally Funk, lifelong aspiring astronaut who at 82 was thrilled beyond belief to finally have at it—throw in the Bezos brothers, and they all get to spend a giddy moment weightless aiming floating Skittles into each other’s mouths.

It just so happens I was actually writing a letter at work this week at the behest of my boss to invite Mark Bezos, who lives nearby and volunteers for the local fire department, to speak to our summer interns about this 10-minute journey in a tiny metal room. Perhaps there will be a different twist on this conversation now.

One seminal moment of my childhood, and a collective one for many, was the 1986 explosion of the space shuttle Challenger. Since there was a teacher, Christa McAuliffe, on this flight, school children all over the country were all watching the launch live—in my case from the clunky TV rolled into the classroom on an A/V cart. Only 73 seconds up the shuttle and its seven passengers went poof, that unforgettable smoke formation in the sky—and our teacher, red-faced, rushed to turn off the TV, a class stunned silent, many of us in tears. Still, this never stopped me from wanting to go to space someday, to see our earth from far above, though I never did anything to make that happen since becoming an astronaut seemed next to impossible; to this day I would still say yes if any of those golden tickets came my way, which would have to be on account of my specialness, not my fortune. Until space calls, I’ve had my share of willful, if less precious, recklessness: I’ve skydived, walking backwards out the open backside of what felt like a flying box truck with a tandem instructor strapped to me. It’s on my bucket list to drift sunset-ward in a flaming basket under a balloon. Somehow airborne human tomfoolery feels way tamer and safer than doing anything comparable in the water, and especially anything that involves going rogue.

Another formative memory of my youth: visiting Niagara’s tourist museum about the independent loons who’ve gone over the thundering Horseshoe Falls in a barrel, or other ridiculous homemade contraptions. The falls has a long history of attracting “daredevils,” who by definition “risk life and limb to be seen.” I wondered if the infamous barrel folks shared the same carefree wealth of our contemporary adventure tourists. On the contrary, in 1901 the very first barreller was actually a woman, Annie Edna Taylor, a 63-year-old former school teacher, who hoped getting famous surviving the falls in a heavy oak pickle jar made to her specifications, padded, and supposedly tested first with a cat, would solve her financial problems. When they recovered her, extremely shaken but alive, she reportedly said,

“No one ought ever do that again.”

No one did for 10 years and but then there began a steady series of copycats through the years that tried to get their 15 minutes of fame in barrels, an attached series of tires, giant rubber balls, metal tube, kayak, jet ski. One guy brought a turtle along; only the turtle survived. This somewhat dated mini-doc said that in the 94 years since Annie’s stunt (whose likeness I have on a magnet on my file cabinet), there were 15 people to attempt the falls, with surprisingly only five lives lost. Surely there’s a tinge of suicidal in this endeavor, or just simply madness. The kayaker apparently had made advance dinner reservations for that evening. The jet skier hoped to bring attention to the homeless population.

Save for the the few who descend falls with containers that don’t even contain them, that was way less Niagara barrel death than I expected or remembered as a kid—odds definitely better than surviving certain subs. If I had to vote for the scariest submarine since Das Boot, it would be Peter Madsen’s. This is a true crime story I’m fascinated by in part because the perp is Danish like me and shares my last name, but mostly because it’s absolutely bonkers. Madsen brings these divergent worlds of space and sea together, as he was both a rocket designer and a deep sea tinkerer, an indie “extreme machine” maker. Considered the Danish Elon Musk, he founded a nonprofit company in 2008 called Copenhagen Suborbitals for rockets and submarines. As if just rockets or just subs alone weren’t enough to invent and engineer.

His Nautilus submarine at 58 feet was the largest private submarine in the world, made for $200,000 by crowd-sourcing. From a great article on this in Wired.com:

Madsen christened the vessel the UC3 Nautilus, after the fictional submarine in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Jules Verne’s antihero Captain Nemo was a figure who lived outside social laws, sailing the seven seas in search of total freedom. Unlike Nemo, Madsen had stayed close to home in Denmark, but he had devoted his life to building audacious vehicles of his own design, ones that might venture high above the atmosphere or down into the depths of the ocean.

[…]

Building something out of nothing was central to Madsen’s philosophy, as was his belief that he should be able to play by his own rules and control his own destiny. He looked down on people for being cautious. He talked about wanting “to be free from authorities” in making his submarines. After he left Copenhagen Suborbitals, he kept a blog about the progress at Rocket Madsen Space Lab. In one entry from 2015 he described his team as people who “all know that they are taking part in a Peter Madsen project, just like they would do if it was a von Trier movie ... the unqualified belief that Madsens crasy [sic] dreams tend to become reality … makes these people invest time and money.”

2017 was its last voyage, when Madsen had an interview date with a rising international journalist from Sweden, 30-year-old Kim Wall. She waved to her friends onshore, including her boyfriend who planned to move with her to China in just days and was actually hosting a goodbye party which she decided to forgo for this last-minute opportunity, as she climbed down the ladder into his black submarine for a test drive with the famous entrepreneur. She didn’t resurface in a few hours as planned. The next morning, Madsen swam up, citing a marine accident. Where’s Kim? Unknown. What became of the boat? Sank. At first he said he dropped her back onshore and continued on into the deep until it croaked. But later he said she died when the hatch fell on her head. He panicked, pulled her out with rope and “buried her at sea.” I love how people go to such great guilty lengths to hide their innocent acts. Ten days later, her body parts started turning up to betray him, as they always do, ready to tell the true tale. Her torso was discovered, then a bag with her head, clothes, knife, saw, weighed down with metal parts. Later legs were found, tied to metal. He changed his story to perhaps it was carbon monoxide poisoning, admitting he dismembered her. Then they found arms. There was no head injury, save for the fact that it was cut off, and her torso revealed many stab wounds. Basically this all amounted to an unfathomable nightmare that I’m sorry to pass along to you. But the ego is the thing that most astounds. The idea that a man can pop out of the tower of his sinking homemade submarine and give a thumbs up, I’m fine. Turns out he was a very twisted fellow who came prepared with these killing tools, after watching however many hours of videos of similarly gruesome acts performed on women. Did he build the whole ship as a sex/death trap fantasy? Were these hidden headquarters on the open sea his private hunting ground?

Luckily the Danish judicial system was speedy and Madsen was imprisoned for life—until one day he wasn’t. He escaped, briefly, running out with a fake gun and fake bomb belt that had security scared for a moment, then they detected the emptiness of his props and brought him back.

I’m not conflating these other extreme sport enthusiasts to the rare person with a death wish or this lone wolf murderer, but when things go so wrong then what do you call it exactly? The most dangerous thread running through these stories is our human proclivity to trust people or companies in a position of authority, to deny our own vulnerability or mortality, to fall prey to charm, fame and charisma, to want to believe a good story. The Niagara daredevils are independent operators largely in their own category (except a few of them that went in pairs and even had sponsors), who have nothing to blame but their own eccentric natures. But there’s something about the futuristic sheen of these enterprises and the successful geniuses behind them that makes everything seem like it will be fine, the risk worth it. No matter that the waivers say death, death, death, assuming you ever read them. There’s the comfort of being contained, whatever the materials. Being in the room where it happens is intoxicating enough, having this kind of access, even if the room is too thin and two miles underwater. Until it’s too much pressure.

Oh wow... have you read "Endurance: Shackleton's Last Voyage"? Very, very good book about exploration, human grit, and... well, endurance.

I remember well the Challenger explosion. I think it was 4th or 5th grade, coming back from lunch. The world changed that day. Innocence was lost.

Wow. And...fascinating.