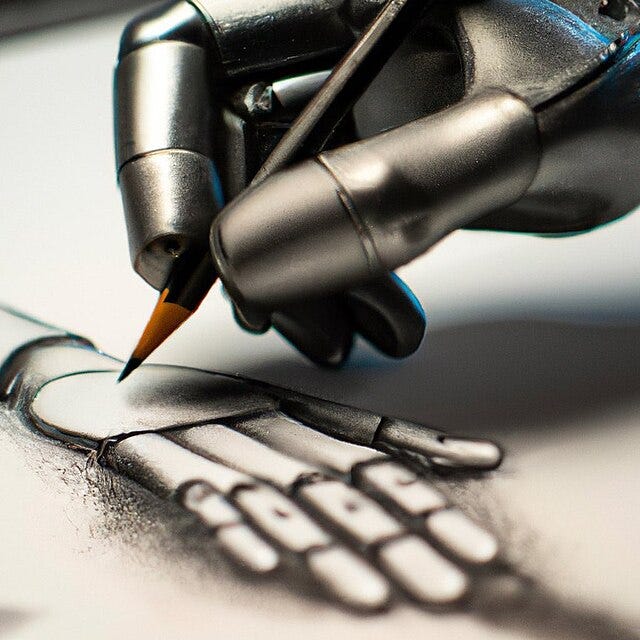

When a robot—perhaps crafted to resemble a human—dares veer too uncomfortably close to anthropomorphic, we humans supposedly tend to get hit with a queasy squeamishness/revulsion. This fascinating phenomenon is referred to as the Uncanny Valley. Follow Substacker Andrew Smith, who takes on many topics in his daily posts that get stuck in my mental craw, introduced me to this murky terrain of the valley here.

More on this from Wikipedia:

The uncanny valley (Japanese: 不気味の谷, bukimi no tani) effect is a hypothesized psychological and aesthetic relation between an object’s degree of resemblance to a human being and the emotional response to the object. Examples of the phenomenon exist among robotics, 3D computer animations and lifelike dolls. The increasing prevalence of digital technologies (e.g., virtual reality, augmented reality, and photorealistic computer animation) has propagated discussions and citations of the “valley”; such conversation has enhanced the construct’s verisimilitude. The uncanny valley hypothesis predicts that an entity appearing almost human will risk eliciting eerie feelings in viewers.

The valley was first named by robotics professor Masahiro Mori in his book from 1970 with a great graph I could spend all day exploring since it includes all kinds of freakery from dolls and puppets to corpses, zombies, and prosthetic hands, charted according to our varying degrees of affinity for them whether in motion or still.

Don’t tell Lisa Frankenstein, or Godwin of Poor Things, but a zombie is, according to this chart, notably less appealing than a corpse, so maybe just leave the poor things alone and don’t try to revive anyone. Well-noted, as I’ve admitted here that I had reanimated my ghoster, which I guess then made him a zombie…and you can just imagine how that enterprise went down. Brains!

So there’s robots becoming too human (which proves problematic for lots of reasons beyond just our knee-jerk repulsion, see: Cybersickness and Marry a Character), but what about the scarier and more popular inverse: when humans become too robotic? I’m far more disgusted by—and worried about—this situation I feel like I’m encountering increasingly often. How many humans do you come across these days who seem to be successfully “passing” as homo sapiens until you get to know them more and discover there’s not much under the hood actually animating them? Shells of humans reporting to work, buying groceries, Pelotoning, and functioning well enough overall, but without the blood and guts. Walking dead. Hollowmen.

To put a label on this, I’ll borrow the words my beloved love doctor Esther Perel keeps tossing around these days: Ambiguous Loss. Color me a superfan, but I listen to every podcast and interview the world renown psychotherapist produces or graces, since, in addition to the nine languages she is fluent in, she is most eloquent in human heart. In every chunk of her content I’ve binged lately—a live conversation with another of my favorites, comedian Trevor Noah; with Brené Brown; with Dan Harper on the Ten Percent Happier podcast—she repeatedly points to this pervasive mournful land of Ambiguous Loss we all live in yet is very hard to map.

According to the Mayo Clinic,

Ambiguous loss is a person’s profound sense of loss and sadness that is not associated with a death of a loved one. It can be a loss of emotional connection when a person’s physical presence remains, or when that emotional connection remains but a physical connection is lost. Often, there isn’t a sense of closure.

This discomforting feeling of dissonance—less obvious and quantifiable than the grief suffered from death but no less painful—can come in a variety of flavors that all taste bad. It can be the complicated loss you may feel over an elderly loved one fading into dementia, the sort of separation we suffered when isolated from each other during the pandemic, a parent leaving the household due to divorce, the empty nest of kids gone to college, missing a person with a drug addiction. More extremely, a no-body homicide. Or, Perel pulls this into the realm of the everyday: the subtle but significant loss we endure now when padded by technology.

On the SXSW stage with Noah below, Perel hits on this around minute 24, particularly surrounding our lost art of listening that I’ve bemoaned recently. We feel the Ambiguous Loss of people in our midst who are there but aren’t present. They aren’t actively engaged with us, just uh-huh-ing and glancing at their phones, or maybe only secretly itching for their phones, those all-powerful robot-human amalgams demanding constant attention. Or maybe they are too busy waiting for you to finish speaking, forming their own words while you talk, needing to top that with a taller tale of their own. True listening she defines as “curiosity,” “a certain kind of engagement with the unknown,” with no expectation or assumptions, no distractions, and involving the “whole body” from ears to eyes, voice, hands.

You listen like that, and the quality of your listening is what will shape what the speaker will tell—how much, how open, how deep… Listening shapes the speaker.

As her own anecdote to what Perel calls our pandemic of “social atrophy” and how we increasingly lack the ability and means to connect with each other, she has launched herself on a traveling roadshow. A love expert on a world tour like a rockstar! She’s filling more intimate, but substantial, venues like the Beacon Theater in NYC as we speak. I have no clue what she’ll do during these live performances, but on the Ten Percent Happier podcast she mentions that at her relationship lectures she tends to ask for those who came alone to please stand up. It often amounts to about a third of the room. She asks the others to welcome them, befriend them, let them not leave feeling like the new kids they came as. After so long on Zoom, she longs to hear them breathe in the same room as her, to see them smile, cry, react. It changes what and how she speaks.

The loneliness that comes with this constant Ambiguous Loss we face in everyday life now is profound and pervasive—epidemic enough that I spent three weeks dwelling on it in a recent trilogy. When thwarted from connection attempts by too many rejections, however overt or covert, you might be inclined to give up and retreat back into your shell. “You can’t break my heart cuz I was never in love,” goes the Odesza song.

I keep telling my kids and they refuse to believe me: There’s no such thing as multi-tasking, something is always sacrificed. There’s no such thing as both tapping at your phone and being able to listen to a person. The person is the one who is slighted in this scenario, made to feel disregarded, unheard, unsafe. Or an example Noah gives: the worst part of performing in a comedy venue is when the waitstaff comes around with the checks and you lose the crowd to calculating the tip.

Talking with Brené Brown, Perel pairs this loss with another term she uses, Artificial Intimacy,

In my world, the other AI is the rise of Artificial Intimacy. The experiences that we currently have that are pseudo-experiences. They should give us the feeling of something real but they don’t.

I am talking to you about something deeply personal and you’re answering me, uh huh, uh huh, and I should be feeling connected, open, vulnerable, but in fact you’re there but you’re not present, and I’m feeling a certain kind of loneliness… Instead of feeling connection, you’re actually grieving.

Has being human become a sort of Virtual Reality game, less shiny and enticing than VR itself?

There is so much to mourn—and fix—in our contemporary culture: the difficulty of connection that many men in particular may suffer, as they’ve been trained by our relatively young Western norms to be stoic, fearless, self-reliant. (“There’s a reason why men die younger and often alone,” Perel tells Harper, adding that there’s nothing intrinsic or genetic in men that makes them emotionally isolated except a more recent cultural invention that can be discarded.) For our own kids, there’s the loss of the sort of childhoods we may have enjoyed, full of unchoreographed outdoor play where we got to learn life. There’s the loss of interacting with real voices in our age of habitual disembodied texting.

I miss voices the most. Alexa, tell me a story.

Interesting take/inversion! I think you have zeroed in on the loss of emotion that makes us less human. I wonder if there are other aspects we consider to be human that we're giving up or shedding unintentionally, like the ability to linger for longer on leisure (accidental alliteration!). I like that you flipped the script a bit.

Thanks, Krista. This might be slightly off to the side, but what you wrote made me think of it. Did I tell you I was in an Apple store and on impulse let a salesperson demo Apple Vision Pro? It was an uncanny experience, so real that you connect emotionally at times to what/who you're seeing. Who knows where this is going, but it would be real easy to see some poor schlub staying at home so that the beautiful singer looks deep into his eyes as she's all but crawling onto his lap, instead of reaching a point of authentic loneliness that forces him out into the world where he might stumble into a connection with a less perfect and idealized partner, but one made of flesh and spirit. It was frighteningly seductive, and scary. You should try it and see.

P.S. And yes, men are really in trouble.