In my household, we hold these two truths to be self-evident:

1. There’s no such thing as boredom. If you’re bored, you’re boring.

2. Weird is natural, weird is good. Normal is the aberration. Normal is boring. Normal is weird.

In the dizzying last few weeks of Kamala Harris’ coming out party as a presidential candidate, the revived Dems quickly coalesced around an invigorating vision of forward vs. backward, hope vs. fear, kindness vs. hate, joy vs. anger, laughter vs. pouting.

I’m in the front row with confetti spray and a t-shirt until the part where everyone starts falling in line calling Trump “weird.” It supposedly started with Harris’ running mate selection Tim Walz, who said, “these guys are just weird,” to the Morning Joe show. And then it spread like California wildfire through the dry desert tinder of all the pundit shows and anyone else available and quotable until it won’t ever stop. Yes, Trump and his VP JD are indeed irrefutably weird—as if that’s any big epiphany?—and certainly labelling him this over and over an infinitum (because now it’s the thing that sticks and grows in this meme moment like no other) is irking him on his golden toilet where he stews about being out-crowded at a rally. How dare you call me weird. Indeed, please stop. Trump isn’t allowed to scorch-earth everything.

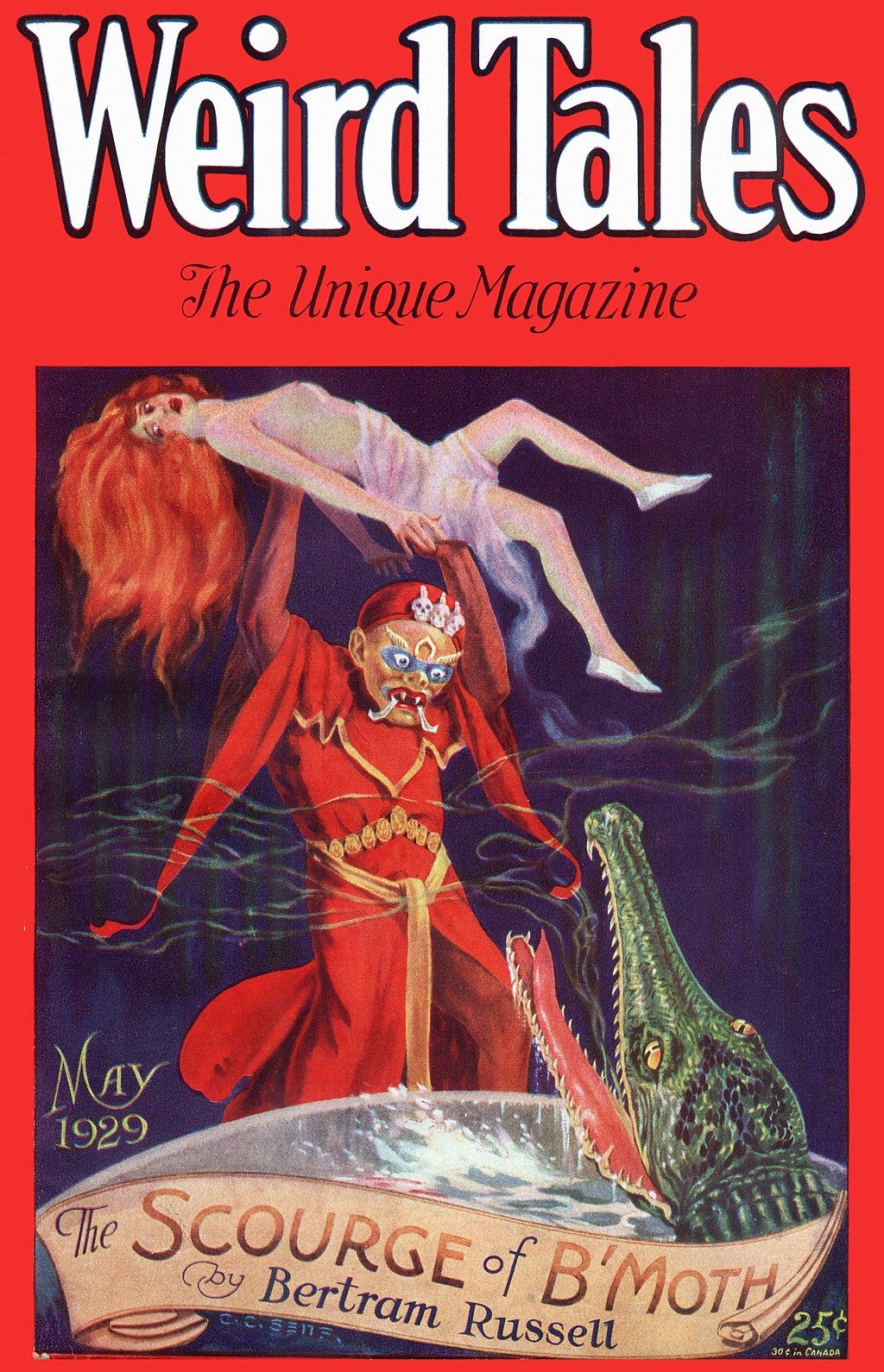

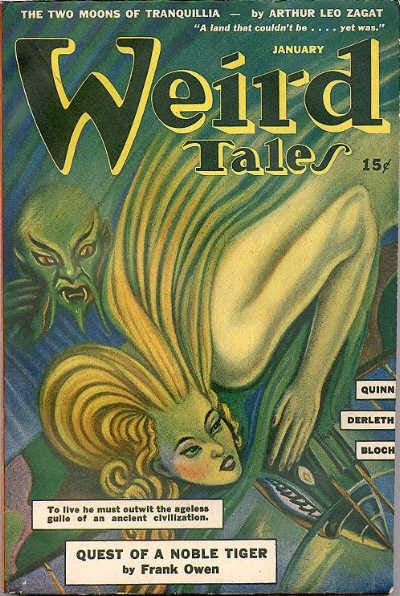

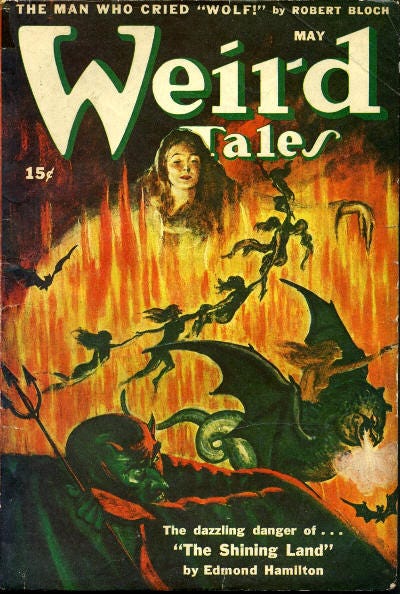

I want my weird back. I’m not the only one, as this lit-infused article by Jason Farago in The New York Times happens to similarly express. Weird is Weird Al. Weird is Bowie, Björk, Tom Waits, Pee-wee, Gonzo, Kate McKinnon’s Weird Barbie. Weird is this unique pulp magazine which launched in 1922 and is still going strong, from which I’ll intersperse some cover art for flavor throughout.

“Weird” is what funky cities at risk of pricing out their messy artiness to gentrification want to fight for and protect. The “Keep Austin Weird” movement came first in 2000. The infectious grassroots energy of this spread to Portland (2003), Louisville (2005), Indianapolis (2013). It’s become almost normalized now to plea to keep your wherever weird, so much so that Baltimore (pretty damn weird if their film director icon John Waters has any sway over it), wants to avoid that campaign in favor of a plea I found on a (very small and old) Facebook group for “Keep Baltimore Inexplicable” (KBI).

A city that has been called:“the southernmost city in the North and the northernmost city in the South;” that goes by the dual nicknames “Charm City” and “Mobtown;” and is best known nationally for fictional TV series about crime (The Wire and Homicide: Life on the Street) and a non-fictional series about cake decorating (Ace of Cakes); is not easy to sum up, or even explain.

In fact, there’s a long list of inexplicable things about Baltimore and Keep Baltimore Inexplicable intends to compile it! And why not? Evidence of a multi-faceted, diverse, and (often) contradictory city is not something to be stifled. Instead it should be celebrated! And indeed, Keep Baltimore Inexplicable is an organization created to do just that.

We call upon the citizenry to ignore the implementation of simplistic labels such as the lamentable, oft- floated, ‘Keep Baltimore Weird’ slogan, or the ‘Greatest City in The World’ tagline featured on the city’s public benches. Baltimore defies this kind of simplistic explanation and you should too!

The group and its 12 followers (count me in for lucky 13!) has some fun facts there to support its treatise, such as Baltimore being the last major US city to get a sewer system (more than 50 years after “early adopters Brooklyn and Chicago.”

Recent efforts however, have shown a sanitation vigor, unparalleled in years past, but with a similar level of inexplicability, calling upon the likes of The Poo Fairy and Recycle Rick to rouse the populace to “Clean Up Baltimore.”

Other evidence of this city’s special inexplicability come in the form of their neighborhood public Salt Box snow removal “system,” and their inscrutable parking signs (pretty typical anywhere if you ask me).

Call it what you wish, but weird is what I encourage chez moi. We don’t strive to fit in. I am proud of one rare achievement of my parenting that my girls don’t aim for “popular.” I had to go to my favorite resource, the good old dictionary, to get a handle on the history of this word which, frankly risks getting dulled into a stupor if we keep applying it to men only unironically wearing makeup.

Merriam Webster defines weird as,

Adjective:

1: of strange or extraordinary character : odd, fantastic.

2: of, relating to, or caused by witchcraft or the supernatural : magicalOr noun:

1: fate, destiny; especially : ill fortune

2: soothsayer

Extraordinary, fantastic! But also: supernatural, soothsaying. It’s so interesting in the footnote to learn how what started as fate generically became the Fates in the form of three goddesses, who were referred to three sisters, and then in Shakespeare (where so much of our linguistic magic happens) the “weird” word in relation to these three took off on its own meaning tangent:

You may know weird as a generalized term describing something unusual, but this word also has older meanings that are more specific. Weird derives from the Old English noun wyrd, essentially meaning “fate.” By the 8th century, the plural wyrde had begun to appear in texts as a gloss for Parcae, the Latin name for the Fates—three goddesses who spun, measured, and cut the thread of life. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Scots authors employed werd or weird in the phrase “weird sisters” to refer to the Fates. William Shakespeare adopted this usage in Macbeth, in which the “weird sisters” are depicted as three witches. Subsequent adjectival use of weird grew out of a reinterpretation of the weird used by Shakespeare.

Or as Farago in the NYT more poetically outlines it:

Weirdness has always been formidable, literally so in centuries past. Before it was an insult (flinged or reclaimed), weird actually signified power—and before it was an adjective, “weird” was a proper noun. In Anglo-Saxon Britain, Wyrd was a pre-Christian personification of destiny, who governed the fate of all things. She is invoked early in “Beowulf,” as the title hero prepares for battle with the monster Grendel. “Fares Wyrd as she must,” says Beowulf to Hrothgar, the king of the Danes. Do not mourn me if I die. The weird is the lord of man.

In later centuries, the Anglo-Saxon Wyrd got tripled, in rough analogy with the three Greco-Roman Fates who spin the thread of human destiny. The Weirds (or Weïrds; the New Yorker-style dieresis signals it was two syllables) became a trio of female seers, most famously in “Macbeth,” whose Weird Sisters foresee that the Thane of Glamis will become king of Scotland. The witches on their blasted heath are weird in the original sense: unearthly, uncanny, what Banquo calls “fantastical.” Their warts and rags may make them scary. Their 5G connection to the spirit realm is what makes them weird.

Even by the 19th century, when “weird” took on its contemporary meaning of oddity or abnormality, it still carried supernatural overtones. Percy Bysshe Shelley writes in one poem of a witch’s tricks as being “A tale more fit for the weïrd winter nights —/Than for these garish summer days.” But we disenchanted moderns, even in weird and wild times, do not have such spooky views of snowstorms. Weirdness lost its paranormal character in the 20th century, and became merely a freakish disruption of the natural order. Norman Bates. Rocky Horror. The outlier, stripped of his eldritch energies, became simply the weirdo.

Just like that, a freakish disruption of the natural order. And then the weirdo explosion. So many words mean weird, and none of them exactly Trump-propriate. From the list of synonyms:

bizarre bizarro cranky crazy curious eccentric erratic far-out funky funny kinky kooky kookie odd off-kilter off-the-wall offbeat out-of-the-way outlandish outré peculiar quaint queer queerish quirky remarkable rum [chiefly British] screwy spaced-out strange wacky whack whacky way-out wild

None of these synonyms work for our deflating antihero. He doesn’t deserve them when there are so many real outré characters out there who are far more deserving. He’s just not that interesting with his same boring two-note story. And yet he’s certainly scary.

The better word for Trump, and a quote from Nancy Pelosi agrees in another article on the matter in The Times, is “dangerous,” but that’s too risky to say out loud. How about “wrong,” she posits.

Our goal is to make sure that Donald Trump never sets foot in the White House. Because he’s beyond weird. I won’t go into all the adjectives.

I think ‘weird’ is too complimentary a word for them. Weird is weird. But wrong is even different. It’s a good word. It’s on the path.

But I think ‘dangerous’ is probably—but it’s not as, shall we say, appealing a word. It sounds confrontational, but I think they’re very dangerous. Some weird people may be dangerous, but not all.

Wrong, dangerous and how about…damaged, demented. Trump doesn’t like being laughed at, as this revealing post from his estranged niece Mary shares in this seminal tale from his youth and a bowl of mashed potatoes getting dumped over his head for tormenting his little brother at a family dinner. Weird is not a word for Trump.

Because I’m empathic to all creatures, let’s say, sad.

Tim Walz again at his own coming out party as running mate: “These guys are creepy, and yes, just weird as hell.” Of course he means none of this in a good way. This is the weirdness that makes us cringe, skeeved, and gives us the heebie-jeebies. Trump’s weird because he would mock weirdness.

From Farago:

But it only lands with force because of a curious—we might say weird—ambiguity in the language. Today, “be normal” and “be weird” have become both antonyms and synonyms: fun house reflections of a dominant American ideology of standing out to fit right in, and self-acceptance as the highest calling. What Mr. Walz is calling “weird” is not atypicality as such, but an up-in-your-business insolence out of step with his American ideal. Fair is foul and foul is fair, as the sisters in “Macbeth” conjured; to be weird is to be normal, and to want orthodoxy is just weird.

Calling Trump “weird” turned out to be a myopic attempt to tap into the zeitgeist which, among other things, remains fed up with how people see the status quo and our trajectory. A lot of this was power-fueled and manipulated by billionaire oligarchs seeking only impunity. But people like Charles Pearce (formally of the Boston Globe) have been warning about a “wilding” of America (starting in Republican circles) since the Obama election if not before. The oligarchs saw it first and took it way more seriously than the Dem establishment, but not to alleviate it. And now that they are in power, they (even the ones without prison time hanging over their heads) may want to ride the tiger out of pure insouciant greed for power and thrills. They also have (in thrall) myriads of trauma addled minions who are dead set on inflicting more trauma and chaos because they feel they have nothing to lose or because they are mesmerized by the deadly siren lure of triumphant domination.

This was fun. And yes, being of Austin (which was so interesting and odd and creative before all the money fell into it) and the fact I moved to NYC because I was a weirdo and wanted to find my brethren and sistern, I will be glad to get the word "weird" back. However, for now I must say, that Dems using it against the Dark Force really takes the wind out of them, as much because of its innocuous-ness as anything else. They *want* to be considered "dangerous" and "radical" and "hateful." All that stuff pumps them up. But to simply call them "weird" (and at first I was not on board with it, but man it is working) is closer to calling them "dorks" or "lame." They want to be feared and Walz is telling them instead how uncool they are, how awkward, how odd. And they *hate* that, because secretly they want to believe they're cool like Bond Supervillians. I agree with Pelosi that the word isn't accurate, but it definitely is tactically effective. I think it also punches at them because conservatives do not want to be weird. They want to be upstanding and "normal." Weird as a word and a concept is not something they identify with or want any part of.