My eighth grade daughter is reading her first Edgar Allan Poe stories in school, our pet is an everlasting black cat named Poe, I just dusted off this beautiful Poe collection on my bookshelf, suddenly there’s a binge-worthy Fall of the House of Usher series on Netflix, and it’s Halloween season in the Hollow—so clearly all signs points to a post about Poe.

The Collection

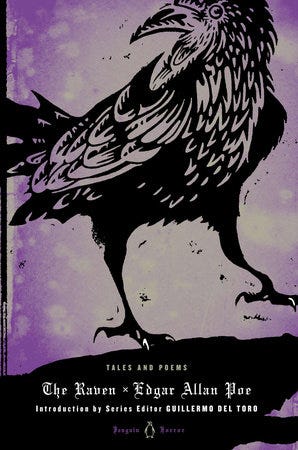

Admittedly I haven’t read Poe since I was my daughter’s age, but I did feel compelled to buy and never read this gorgeous collection a decade ago with its pleasingly tactile raven cover, black-edged pages, and an intro by director Guillermo del Toro. It is part of Penguin’s six-volume series featuring the best in classic horror that he helped curate, including Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House, Frankenstein, and others. So many Poe titles reverberate with their own fame whether or not you’ve actually read them.

From the publisher’s notes:

The Raven: Tales and Poems is a landmark new anthology of Poe’s work, which defied convention, shocked readers, and confounded critics. This selection of Poe’s writings demonstrates the astonishing power and imagination with which he probed the darkest corners of the human mind. “The Fall of the House of Usher” describes the final hours of a family tormented by tragedy and the legacy of the past. In “The Tell Tale Heart,” a murderer’s insane delusions threaten to betray him, while stories such as “The Pit and the Pendulum” and “The Cask of Amontillado” explore extreme states of decadence, fear and hate. The title narrative poem, maybe Poe’s most famous work, follows a man’s terrifying descent into madness after the loss of a lover.

And from Guillermo’s excellent intro to the entire series:

To learn what we fear is to learn who we are. Horror defines our boundaries and illuminates our souls. In that, it is no different, or less controversial, than humor, and no less intimate than sex.

About Poe specifically, Guillermo writes about how his misinterpreted autobiography (as a mere madman, an addict) is all bound up in his fiction, how he focuses on outsiders and goes deep into the dark recesses of the mortal mind. How a “good” man might turn and poke a cat’s eyes out. How the fatal crack of the house comes from within.

The Cat

I don’t know my cat’s origin story since I didn’t meet her at birth but I start the clock in October 17 years ago when she found her way to me in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn. My neighbor/bartender stashed her in my bar garden after finding her wandering the nearby park. She had left a voicemail on the bar phone that there was a cat in my garden, which I didn’t hear right away. A day later, I figured this was yet another feral stray which would have climbed over the garden wall by now, so I ignored it another day. Eventually I finally opened the back door to come upon a sweet black kitten mewing. You didn’t say it was a kitten! But I couldn’t keep any kind of cat, no matter how small—not allowed in my bar nor my apartment—and I thought I could remain immune to the cuteness of a kitten if it wasn’t for the part where I started brainstorming good black cat names. The minute I name something is when I’m hooked. Naming is everything to me, the container often creating the thing itself, or reserving the space for it. I remembered that the author Poe had a story called “The Black Cat,” however dark it was, so “Poe” she was and only then did I decide to keep her.

Poe predates my children and she might, however many lives in, outlast them. She was a favorite at the bar and a shocking showstopper when she brought in unfathomable prize creatures to my customers. How sweet and scary.

This brings me to introducing my first foray into sharing new fiction here—albeit behind a paywall if you don’t mind (and check out other short stories from my archive that aren’t). Going forward, I hope to write more fiction on this platform and save it for paying subscribers. This is a what did that cat drag in now tale, inspired by a true story of the cat and its surrounding humans gone wild, tangentially riffing on the Poe tale, and very much in tune with what the Usher series takes to the extreme.

The Hollow

I was always a person very partial to Halloween. The bar was full of the theme parties I used to throw for fun and then became burdened by professionally. I hosted Halloween seven times a year, with different themes, on the 31st of any month that had a 31st. This lifestyle was exciting, and exhausting, but eventually I had a human child in addition to a bar and a cat and books, and my new husband and I were scouting up and down the Hudson for viable properties with tiny yards—as you do when you get sick of navigating crosswalks and subways with a stroller.

We were driving south on Route 9 on our way back to the city from Beacon when we passed a massive cemetery lined with stately sycamores, and I swear I saw the sign “Welcome to Sleepy Hollow” through a fog settling in the dusk. It couldn’t seem more fictional—so much so, I wondered if we had hallucinated the place. I didn’t know a Sleepy Hollow existed outside of a story so of course I went home and immediately found the cheapest house there on the market, right in clear view of the Tappan Zee. We were under contract within weeks and started our little idyllic life here in 2009 in a village I was now obsessed with.

Living in Sleepy Hollow comes with its readymade mascot, a headless horseman they trot out for every occasion, street signs (and now fire hydrants) in orange and black, and all hail Washington Irving with his Sunnyside gingerbread cottage down the road and simple grave in the cemetery he started. I should keep my seminal American storyteller loyalty clearly in his camp, but I have to admit—sacrilege—Poe has historically taken a deeper hold on me. It was his stories that infected my brain at a young age and served as a gateway drug to later taking on all of Stephen King and now decades later, my macabre fascination with true crime and all things that go bump in the night. Though they both are often referred to as the founding father of the American short story, I’d choose Poe as more of my fictional founding father.

From his narrator’s approach to the wretched House of Usher:

During the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country; and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher.

And from Irving, nearing Sleepy Hollow:

From the listless repose of the place, and the peculiar character of its inhabitants, who are descendants from the original Dutch settlers, this sequestered glen has long been known by the name of SLEEPY HOLLOW, and its rustic lads are called the Sleepy Hollow Boys throughout all the neighboring country. A drowsy, dreamy influence seems to hang over the land, and to pervade the very atmosphere.

Edgar Allan Poe lived from 1809 to 1849, while Washington Irving was born sooner yet lived longer: 1783 to 1859. In 1819, The Sketchbook containing The Legend of Sleepy Hollow was first getting published in serial form; Poe’s first story came out in 1832. So they were contemporaries, though Irving was the elder who had a big head start and fame first in these fledgling American forms, and they even corresponded. Irving, somewhat snottily, praised in 1839 one “little story” by the young Poe and critiqued another (likely “Usher”): “In your first you have been too anxious to present your picture vividly to the eye, or too distrustful of your effect, and have laid on too much coloring,” he writes. “That tale might be improved by relieving the style from some of the epithets.”

Admittedly both are Romantics spewing purple prose but Poe skews to horror while Irving leans to humor. In fact, the Legend is a bit miscast as a spooky tale when it is way more of farce. The famous ending moment of Ichabod getting run out of town after being chased by a headless horseman tossing a pumpkin is likely more of a prank from a bully than a haunting. Poe is far more morbidly obsessed. The Sketchbook collection that contains Legend and Rip Van Winkle is surprisingly also full of short sketches (essays) fixated on customs from England, still a touchstone of how Americans should be at this adolescent stage of their cultural development. Even though I wrote a new intro to his collection for the 200th anniversary edition, if I were being honest I’d tell people to skip ahead to the stories I know they will anyway. This is why I want to take advantage of the public domain license and publish just the few stories I feel like and put in some art and a new intro (stay tuned).

In the meantime, Poe is more Halloween-appropriate should we ever decide to take on a second, if honorary, lit-legend here in the Hollow. We have a bit with seasonal events that have included “Nevermore,” a circus-theater adaptation of “The Raven,” and “An Evening with Poe,” an actor’s narration of stories about and tales from the man who did live in a cottage only 20 miles ago in the Bronx in his final years, adding to the many cities that can claim him from Baltimore to Boston.

To follow up on last week’s post of Last Words, his attending physician reported that Poe’s final words, after being found “delirious and disheveled” in Baltimore and taken to the hospital, were, “Lord, help my poor soul” before dying at the age of 40 on October 7, 1849. I don’t know what he felt about the Lord, but we certainly learn much about the poor soul from his oeuvre, which brings us to…

The Ushers

If you’re like me, you’ll think this very well orchestrated bloody mess is a hoot—smart and horrific.

Rolling Stone’s review, ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ Is a Literary Orgy of Death, likens the Netflix series to a “highbrow American Horror Story” and puts it in the context of other Mike Flanagan series like Hill House which I also just started watching.

Like The Haunting of Bly Manor, the new show is a mash-up of the works of a particular author—in this case, Edgar Allan Poe. The framing device roughly follows the titular short story plot, as wealthy Roderick Usher (Bruce Greenwood) tells prosecutor C. Auguste Dupin (Carl Lumbly) the story of how his family came to ruin. But there are Poe works incorporated throughout, like a younger Roderick (played in flashback by Zach Gilford) writing the poem “Annabel Lee” as a tribute to his first wife (Katie Parker), or episodes getting familiar Poe-ish titles like “The Masque of the Red Death” and “The Pit and the Pendulum.” If you have only a casual history with Poe, or don’t know his work at all, the story still works on its own terms. It’s just a bonus if you understand the importance of ravens, or why Roderick and his sister Madeline (Mary McDonnell) will at times stare meaningfully at a basement’s brick wall. And some references are just Easter eggs, like Dupin being named after a recurring Poe character who is widely considered the protagonist of the earliest fictional detective stories.

They say Easter eggs, I say Halloween candy. It’s been a dirty treat to watch this series, though, as the author of the above also notes, it’s perhaps a bit rich and rapid-fire to take on in binging succession to meet this deadline the way I have—rich, or disturbed. I love teasing out the Poe references and quotes from the sea of depravity, hallucinations and drugs, enjoying the names like Annabel Lee, Lenore, and Tamerlane (from poems by those titles), and others like Prospero who often star in the stories behind the episode titles. Lines that Poe wrote emerge sprinkled into regular conversation or just, why not, spouted off verbatim in huge passages:

All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.

The flurry of sibling death (another large family like Hill House) is dizzying, each to their own demise in dramatic, gross ways worthy of the movie Seven and its deadly sins, where one’s worst fears and flaws lead to their own specifically tailored exit.

There’s big pharma in the mix and a critique of wealth that comes at such a moral cost, as the Usher family is akin to the Sacklers in Dopesick, with their Fortunato fortune made from peddling opiates to the masses, effectively addicting and killing millions. There are many “bastard” children in this family which makes for great cast diversity, as the dad had all kinds of lovers and surprise children in his history, who are each given a seat at the table although it comes at the price of fierce rivalry and mistrust if not loathing. One son is referred to as an XBox Gatsby, another a Gucci Caligula. All superficial and awful in their own unique ways, yet not without the pathos that makes us care for them as they suffer and cause suffering in equal measures. Most suffering is the patriarch, who narrates these tales to his sympathetic yet longstanding nemesis August, the assistant US attorney trying to bring the Ushers down in court, while the family proves way more effective at destroying themselves all on their own. My favorite line from the father:

There’s no such thing as a painkiller.

And that black cat. My friend rightly noted, “you will never look at your black cat the same way again,” and that’s partially accurate. I already know the seamy side of my cat and choose to stay with her the same way she does with me. Our loyalty runs deeper than Usher.

1. "It’s been a dirty treat to watch this series"

Nothing other than to say: I like this, and I'm stealing "dirty treat."

2. Mind if I quote this piece in my upcoming Macabre Monday post? I think this will tie in perfectly, and it's a nice setup for what I want to do!

I love this time of year.

Thanks for the great Poe and Halloween-o stuff! And also, anyone raised in the vicinity of a farm will tell you to never name an animal that you were planning to have for dinner some day.