“Remember you must die”

This is the translation of memento mori from the Latin. The greatest truth that binds us. While constantly “remembering death” (the fact that you will die, that is) greatly informed the living mindsets of ancient Greeks and Romans, and infuses much of the symbolic, artistic, cultural, religious and philosophical output of the world ever since, we contemporary Americans like to arms-length our inevitable mortality into such a far-fetched abstraction that it hardly exists until it catches us unawares.

As long as you surgerize your face and body enough, you can defy aging. If you’re rich enough, perhaps you might consider self-freezing in the hopes of later thawing. No matter if we destroy this planet because we can migrate to Mars. Manifest Destiny unlimited as our lifespans expand westward but then we might not want to actually see the detritus of that: we shove our diseased and demented elders into nursing homes at debilitating cost rather than collectively support better ways to keep families intact and aging in place. Out of sight, out of mind.

In times of trouble (daily!), I tend to repeat the mantra “all of this temporary” (thanks to the Halsey song “Bells in Santa Fe” that has been constant in my head for years from my jogging soundtrack). Favorite holiday is Halloween of course (where I practically have as a house rule that costumes must be dead, scary, gross or spooky). Second-place goes to the Mexican tradition of Día de los Muertos, Day of the Dead. I was happy to once attend a Day of the Dead celebration at the Hudson Valley Writers Center, and found myself—typically terrified of impromptu public speaking—compelled to stand before the shrine table of memento mori (the phase also connotes objects we use to remember the fact of death or our loved ones), to share something about my then-recently deceased yet forever larger-than-life father.

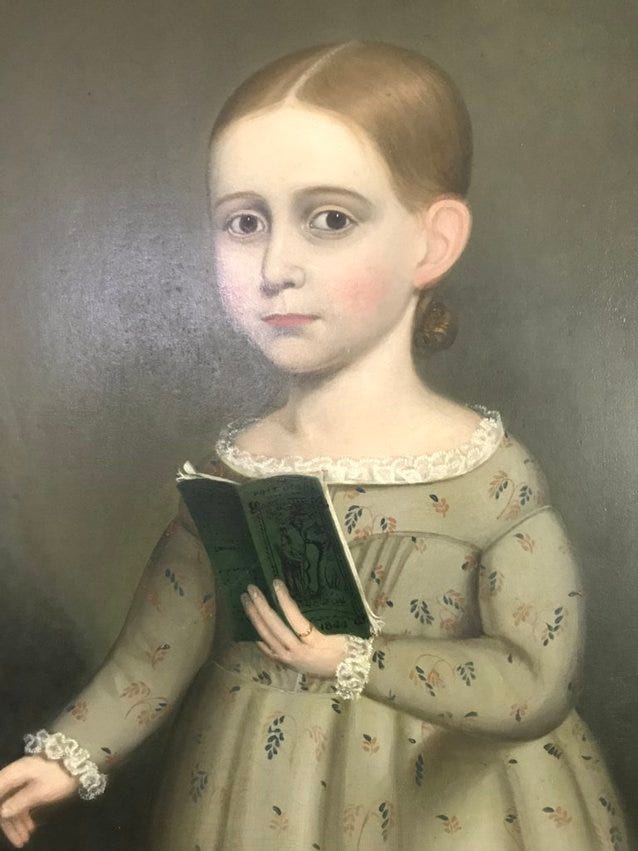

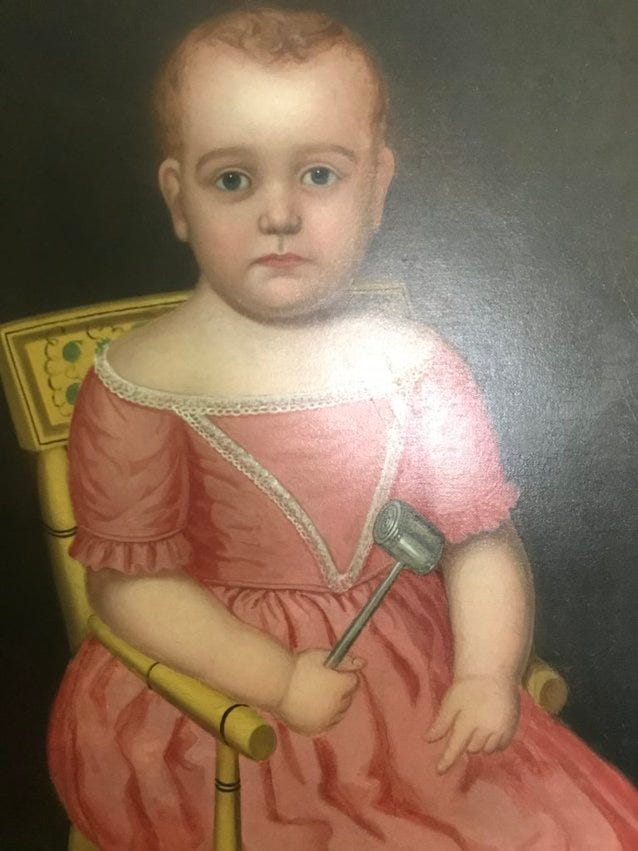

Having tangible objects tucked away (a wedding ring, beloved nicknack) to remind us of our departed loved ones is one thing, but back in the day these might take the form of actual post-mortem photos of your loved ones propped up for posterity while dead, often with the poor grimacing living family surrounding. Before the advent of photography made this possible and popular by the mid-1880s, you might have, should you afford to, gone so far as commissioning a posthumous portrait painted of your loved one, like this trio of young girls I came upon in the back room of a historic house museum in Marblehead, MA on our pilgrimage to Salem, which I’ll intersperse here. Only when my daughters and I were standing there gazing at these unlabelled paintings of girls holding things like a small bible or mallet, wondering why they gave us a tinge of the heebies, did the docent come up to explain how we weren’t wrong. “See the flower drooping in her hand,” she pointed to this girl below. “These are children who had died young and were painted after.” I can’t help but try to imagine the logistics and time commitment of that, verses the quick flash of photography. The ability to not only tolerate death but to pose it and linger around it for days on end was perhaps more normalized then when it was a constant. In the ages of plagues, it wasn’t a given that your kids would survive long—if you lost a Samuel, you’d name the next boy Samuel and the next until one stuck—death was a daily part of life.

Reminders of life’s bitter demise come to us daily in the news, should we choose to engage in paying attention, but usually remain distant until that rare moment it hits home despite our best efforts. This week brought both more unfathomable tales from afar—missiles on hospitals!—and for a friend, learning that his childhood friend had suddenly died in the middle of the night for no apparent reason (yet), a doctor with three young kids no less, only 40 years old and in good health. From both types of shock, we lament the wrongness of these unexpected losses, lives taken too soon, mass or individual, certainly too young and undeserved, and can consider what defines a “good” death or “bad.”

Composed Close

You might prefer instead to imagine you get a staged yet relatively painless death where you know it’s looming, have time to sort your estate and make peace, say goodbye, write a profound note, and, should you and your loved ones be so lucky, even compose something stirring to say in the final moments. Neither of the above scenarios—surprised by bomb or snatched in sleep—offer the chance of any reflection upon one’s own imminent dying or to convey any messages. Only in retrospect in these tragedies can those left behind try to think back on what the deceased might have said to them last, which very well may be something messy or mundane.

My father’s death bed was attended to only by my mom in the end who heeded his constant calls to her as she did in life, “Jo, Jo, Jo,” he summoned for days with increasing frequency. He knew this was coming and certainly had time to plan and make peace but that wasn’t his style; he yelled about his shriveled legs not being exercised enough. He assumed he’d be phoenixing from hospice intact, and was bitter about how challenging that was proving. He hardly let my mom take a break to go buy a few food items and wouldn’t let the hospice nurse anywhere near him for a bath. In the end he wanted pills, and something like “Jo, get my pills” was his last utterance, which isn’t romantic but real. And surely this would have been better had she known it was time to open the “comfort kit” in the fridge with the morphine—which makes me wonder how many last words are rendered more poetic with an opiate. My mom describes the moment shortly after he took what was basically nothing but a placebo of some vitamins, when she heard gurgling as if underwater coming from within his body cavity and the click of the “death rattle” in his throat. She was worried that she said “I love you” only after he passed, but a friend consoled her that his hearing might have been the last thing to go.

My mother’s mother launch (to heaven?) from her home hospice death-bed was an event I was privy to in my college years. I look back on it as one of the most profound experiences of my life; it was an honor to be there. Her daughters and myself were there comforting her, massaging her stiffening limbs, swabbing cracked lips with a moistened pink lollipop of a sponge, while the men couldn’t handle any of this and wandered off to more pressing distractions. At some point she had stopped talking and perhaps gone out consciousness, until she stirred with eyes suddenly opened to announce, “I’m coming Jesus.” And this atheist believed her. My watch had stopped the night before at the very time in the morning she happened to pass. I came to learn that what you believe is true for you, we make our own realities, and when I did feel inclined to pray in subsequent years, I prayed to this grandma rather than some god since at least knew she was out there in the realm she conjured.

There are many well-composed famous last words, which really has me thinking if you want to compete you’d do well to work on some pre-death sentences, the same way you might prepare your will. But so much depends on time and context. Perhaps the working draft could be ongoing in your Notes app and you’re continually editing, right up until you meet your maker. Maybe you prefer improv. I can conjure no wisdom for this yet beyond the fact that I have no wisdom, and much less the closer to death I must get.

Last week I started my October-induced descent into Madness, and now to go deeper on the theme of this most macabre season, I’d like to compile, and sort, some of the best last words I could find kicking around online. Not to overgloom you, but perhaps to inspire.

Last word, singular:

Joseph Wright, linguist who edited the English Dialect Dictionary, on his deathbed: “dictionary”

Italian artist Raphael: “happy”

Composer Gustav Mahler, conducting an imaginary orchestra as he lay dying: “Mozart!”

Writer T.S. Eliot whispered the name of his wife: “Valerie”

Surgeon Joseph Henry Green checked his own pulse: “Stopped”

When the party’s over or just getting started:

There’s a last letter commonly attributed to Apple founder Steve Jobs denouncing wealth which later got debunked, but according to his sister, his actual last words were, “Oh wow. Oh wow. Oh wow,” which makes us wonder what he might have been seeing.

Birth control advocate Margaret Sanger: “A party! Let’s have a party!”

Ludwig van Beethoven: “Plaudite, amici, comedia finita est. (Applaud, my friends, the comedy is over.)”

Authors of course, at the ready:

Vladimir Nabokov, also an entomologist: “A certain butterfly is already on the wing.”

Rainer Maria Rilke: “I don’t want the doctor’s death. I want to have my own freedom.”

Emily Dickinson, sounding like her poems: “I must go in, for the fog is rising.”

Jane Austen: “Nothing but death.”

James Joyce: “Does nobody understand?”

Gertrude Stein: “What is the question?”

Unfinished business:

Sir Isaac Newton: “I don’t know what I may seem to the world. But as to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore and diverting myself now and then in finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than the ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”

Leonardo da Vinci, despite his masterpieces: “I have offended God and mankind because my work did not reach the quality it should have.”

John Arthur Spenkelink, executed in Florida in 1979, spent his final days writing this in various mail: “Capital punishment means those without the capital get the punishment.”

Revolutionary Pancho Villa: “Don’t let it end like this. Tell them I said something.”

All you need is love:

Actor and comedian W.C. Fields to his longtime mistress: “God damn the whole friggin’ world and everyone in it but you, Carlotta.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in his garden, turned to his wife and said, “You are wonderful,” clutched his chest and passed.

William Henry Seward, U.S. secretary of state and architect of the Alaska Purchase, when asked if he had any final words: “Nothing, only ‘love one another.’”

Before Ernest Hemingway shot himself, he told his wife: “Goodnight, my kitten.”

Sarcasm/cynicism:

Frank Sinatra: “I’m losing.”

Karl Marx, when his housekeeper asked if he had anything he wanted to say: “Last words are for fools who haven’t said enough.”

Groucho Marx: “This is no way to live!”

Sir Winston Churchill: “I’m bored with it all.”

To God or not to God:

Actress Joan Crawford of “wire coat hanger” infamy yelled at her housekeeper, who was praying: “Damn it! Don’t you dare ask God to help me!”

Alfred Hitchcock: “One never knows the ending. One has to die to know exactly what happens after death, although Catholics have their hopes.”

Max Baer, boxer: “Oh God, here I go.”

Voltaire, in response to the priest at his death bed asking him that he renounce the devil: “Now, now my good man, this is no time to be making enemies.”

Potty talk:

Elvis Presley, famously expired on the toilet after announcing, “I’m going to the bathroom to read.”

The Comtesse de Vercellis apparently let one rip for her RIP moment: “Good. A woman who can fart is not dead.”

Finally, the sun sets. From the intro I had the privilege to write for the 200th anniversary edition of Washington Irving’s classic Sketchbook collection, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Other Stories, comes:

On Nov. 28, 1859, the family enjoys an exquisite Hudson sunset outside their dinner window. [Nephew] Pierre writes, “The whole party were lost in admiration of one of the most gorgeous sunsets I have ever beheld… Mr. Irving exclaimed again and again at the beauty of the prospect. How little did any of us dream it was to be his last sunset on earth!” Irving later proceeds to his room with niece Sarah helping with his medicine. According to Pierre’s account from Sarah, Irving bemoans having to turn the pillows yet again, and asks something to the effect of “When will this end?” Holding his heart, he crashes to the floor beside his bed.

When will this mortal coil end? We have no clue. Should we get a heads up first, may we have the luxury of composing a moment of difficult joy, morphine, a loved one, a few fine words. In the meantime, remembering you will die is the best way to live.

Death is such a funny thing in western culture. We approach it by... well, by avoiding approaching it!

I've long been drawn to artists unafraid to talk about death. Folks like Orozco (muralist), posada (printer), Poe (poet/writer), Sylvia Plath, and countless musical acts from The Beatles to Napalm Death continue to inspire my own approach.

"My watch had stopped the night before at the very time in the morning she happened to pass. I came to learn that what you believe is true for you, we make our own realities, and when I did feel inclined to pray in subsequent years, I prayed to this grandma rather than some god since at least knew she was out there in the realm she conjured."

How beautiful. Thank you for sharing.

p.s. My favorite fictional passing was Admiral Kirk's from Star Trek: "Oh my."