In The Handmaid’s Tale—which I’ve finally just read and then binged obsessively within a one-month Hulu trial—Mayday is both a distress signal and the underground network which will suddenly activate in unbelievable ways to, say, transport an abused Handmaid and her kidnapped baby from awful Gilead to a new free life in Canada.

The male-and-madness ruled theocracy of Gilead (which overthrew the US government as we know it), and efficiently converted any underlying shitty tendencies into absolute shit, rings a little too true now more ever in the nearly four decades since Margaret Atwood hatched this imaginary world in 1985. Just in the news this week or lately: Harvey Weinstein’s rape conviction overturned in New York; the Supreme Court debating whether a former President can be granted immunity from any and all official crimes committed; now that Roe vs. Wade is gone and the states can go rogue, perhaps police issuing pregnancy tests at borders can be a thing as Alabama politicians call for the prosecution of women who travel for abortion; frozen embryos are considered people with more rights there than women apparently; and Arizona reboots a severe abortion ban from 1864.

Help!

As we near the first of May—a hopeful day where we fully embrace spring (out with the showers and in with the flowers), which can mean, in my case, eagerly getting saplings in the ground that might otherwise be eaten while incubating inside with my eager old housecat—there’s the deeper history of this “Mayday” to acknowledge, that double-edge of danger that comes with redemption. What was more pagan in Europe became our original labor day in the States, in commemoration of the Haymarket Riot of Chicago, 1886. And now there are the wars of the world we protest.

“It’s a beautiful May Day,” Ofglen says to Offred (just some of the women named after their masters) in the Handmaid’s series, and it is, but they are also at the funeral procession for a miscarried fetus in a culture that values the fetus über alles. Offred remembers the conversation she once had with her pre-Gilead husband on the French origins of the term.

From howstuffworks.com, the need for an international distress signal arose after WWI when air traffic was on the rise:

Frederick Stanley Mockford, a senior radio officer in London, was put in charge of finding a good distress signal. He reasoned that because so much of the air traffic flew between Croydon and Le Bourget Airport in Paris, it might make sense to use a derivative of a French word.

He came up with “mayday,” the French pronunciation of “m’aider” (“help me”), which itself is a distilled version of “venez m’aider,” or “come help me.” The US formally adopted “mayday” as an official radiotelegraph distress signal in 1927.

Due to radio interference and loud ambient noise, pilots are told to repeat the word three times: “Mayday, mayday, mayday.” The repetition also serves to help radio operators distinguish the transmission from others that simply refer to the mayday call.

Why not SOS?

Why not just use the standard “SOS” call that navy captains use to signal distress? Well, ships communicated through telegraph using Morse code, and this technology made “SOS” (three dots, three dashes, three dots) unmistakable. By contrast, aircraft pilots used radio calls, and “SOS,” owing to its consonants, could be misheard as other letters, like “F.”

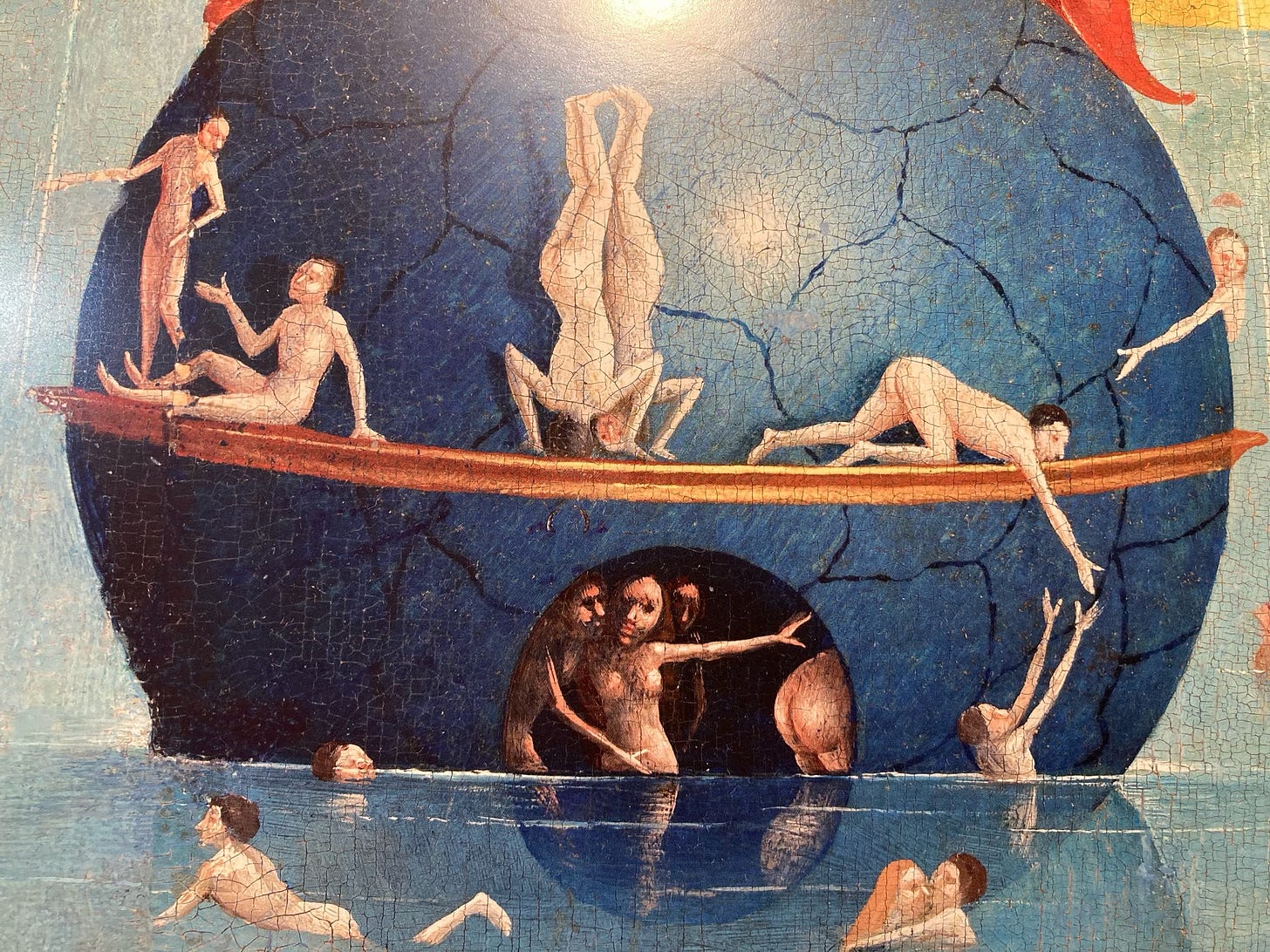

This S and F interchange reminds me of the letter confusion when I just picked up some prints by 1500s Dutch master Hieronymus Bosch from my friend who had no use for them and thought of me after my article on density vs. the Horror Vacui. At first I thought there was a typo on the boxset (looks to me like “Bolch”), until he reminded me how S’s then were sometimes F’s depending on their position in a printed word. So Heironymus was Heironymus with an S in the final position, but Bosch became Bofch with an internal S depicted as an F, of course! And of course the paintings offer endless dark details that I am compelled to intersperse throughout this post.

After trying too often to decipher the names of people who call Town Hall and leave their messages on my voicemail too quickly, I can just imagine the trouble of having someone calling for an SOS and getting a FOF by accident. Au secours!

Mayday, mayday, mayday comes in threes to be extra-clear, but we MOMs know it’s so hard to ask for help just once let alone thrice. We’re out of practice, or never knew how to begin with. Once when I ran a nonprofit and said something bemoaning single motherhood after divorce, the director of the board, a widow, chastised me. “Your daughters have a dad, he’s not dead, you’re not a single mom.” I felt terrible but also a little annoyed that those who alternate equal custody can’t lay claim to the isolating feeling we suffer of going it alone, even if partially. When it’s kid-time on our watch, we are most definitely alone. There’s no partner around to soften any struggles; in fact the contrast of having time off from kids when they are parented totally different by someone else may make the time-on time even harder.

Gone are the extended family networks of Bosch-Bofch-Bolch times when grannies and aunts might be nearby in the village or even in the same household. For all the terribleness for women in Gilead, you have to give the founding fools minor credit for at least surrounding women with women. The red riding hood Handmaids walk to the market in pairs, they give birth in a chanting hoard, their households are rich with “help,” however captive they are, that include those solid ever-enduring kitchen Marthas. Never mind how they empower the Aunts as punishers—I’ll save that for another day. In an upcoming post, I will outline the whole world structure that Atwood has built with an eye to every last detail. She’s created—and the show further fleshes—a whole very complicated, if extremely flawed, society, and on some twisted level it works.

We suffer now from a lack of society, from the way real life is stealthily being supplanted by all things online. IRL morphs into URL. I have long endured the subtle feeling of being a motherless mother, among the ambiguous losses I defined last round, of having a mother but more in name only. She wasn’t a nurturing, present mom with the advice and support I have needed and longed for, especially heightened when pregnant and then caring for kids ad infinitum. Faced with a lack of female society—who among us has a network of Handmaids and Marthas?—I’ve been trying to do better at creating one. Making new friends (I’ve managed to find a few lately!) and reconnecting with lapsed ones.

The loneliness that gnaws at us is a silent cry for help. Who is Mayday?, Offred (June) asks when she gets secreted out of this Bosch sort of Hellscape to reunite with her long lost husband in O Canada at last. Mayday is anyone, Mayday is whoever and whatever you want it to be, Mayday is you. It’s a state of mind. Ask for help, help others, and you will be helped in return.

We all need help but don’t know how to ask, or where to even begin. An article in Harvard Business Review helps us ask for help, starting with what’s holding us back:

The fear of being vulnerable

The need to be independent

The fear of losing control

Overempathizing with others

A sense of victimhood

And then outlining steps we might take to begin seeking support:

Seek counsel - get a coach, or therapist, or how about a mentor. There are experts and advisors out there, and if it makes you feel better, you can even pay them

Reframe - turn any possible vulnerability into a win-win in which you give others a chance to step up

Make your request meet the so-called SMART criteria: an ask that is Specific, Meaningful, Action-oriented, Realistic, and Time-bound

Communicate - being more authentic and open lets people in

Practice - these are skills that bear repeating to become normalized

And what about the helpers?

Stanford social psychologist Xuan Zhao emphasizes what she learned from her research that while we may be shy to ask, others may be more eager than we realize to help. We can argue all day about altruism—maybe there’s no such thing as a good deed in the purest sense, because underlying might be secret selfish motivation: it makes us feel good! But the result is still the good deed and feeling good (win-win). From Stanford.edu:

We shy away from asking for help because we don’t want to bother other people, assuming that our request will feel like an inconvenience to them. But oftentimes, the opposite is true: People want to make a difference in people’s lives and they feel good—happy even—when they are able to help others, said Zhao.

“We love stories about spontaneous help, and that may explain why random acts of kindness go viral on social media. But in reality, the majority of help occurs only after a request has been made. It’s often not because people don’t want to help and must be pressed to do so. Quite the opposite, people want to help, but they can’t help if they don’t know someone is suffering or struggling, or what the other person needs and how to help effectively, or whether it is their place to help – perhaps they want to respect others’ privacy or agency. A direct request can remove those uncertainties, such that asking for help enables kindness and unlocks opportunities for positive social connections. It can also create emotional closeness when you realize someone trusts you enough to share their vulnerabilities, and by working together toward a shared goal.”

At work this week I was witness to a choking incident, and a rescue. An elderly man standing alongside his car asked my coworker, who was closer than I in the Town Hall parking lot, if he knew the Heimlich, and said he was choking. My coworker went right up without hesitation and squeezed a raw carrot right out of him. The quietness of the moment, from both of them—the calm in asking for help by the one in danger and the ease of the one who saved—was surreal, and beautiful. Serendipity of time and place and these two crossing paths, with me just being an awed reporter, commending them both, and later getting on the All Employees email to let everyone know about the everyday act of heroism in their midst, and our proximity always to mortality. Beware the carrot!

In the final days of National Poetry Month, I’ll share the little phrase that often repeats in my brain, the title of Stevie Smith’s poem, “Not Waving But Drowning.”

The whole poem:

Nobody heard him, the dead man,

But still he lay moaning:

I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning.

Poor chap, he always loved larking

And now he’s dead

It must have been too cold for him his heart gave way,

They said.

Oh, no no no, it was too cold always

(Still the dead one lay moaning)

I was much too far out all my life

And not waving but drowning.

I seem so friendly, they say, with my smiling and waving. But that’s my cry for help.

Such strange times. Even so, I remain hopeful. Along with my fear rising, so has my hope. The worst is the Supreme Court stuff, but still, I can't imagine in the end it will take the devil's path.

Yes, nightmarish as Gilead is, there's a real logic to it, which is interesting to look at. I too read it late, maybe 10 years ago. I was pleasantly surprised to see - of all things - a sympathetic rendering of male characters. Because a system that rigid would break them too, even if they carried the overt power. This is one reason the book works so well - it's not some screed, but a dimensional rendering of a terrifying yet believable world with its own logic.

I need to learn the Heimlich!