In recent weeks I’ve spiralled Heptapod ink swirls, explored a UFO Fair and its dubiously coiffed abductee, and now—before I leap into the grander philosophical matters of universal Aloneness vs. The Other as promised—I’d like to stop and take stock of the actual aliens. What might they look like? Barring a break-in at Area 51 or an interstellar field trip, examining them requires navigating the wilds of internet “research” and/or a heavy dose of imagination (preferred).

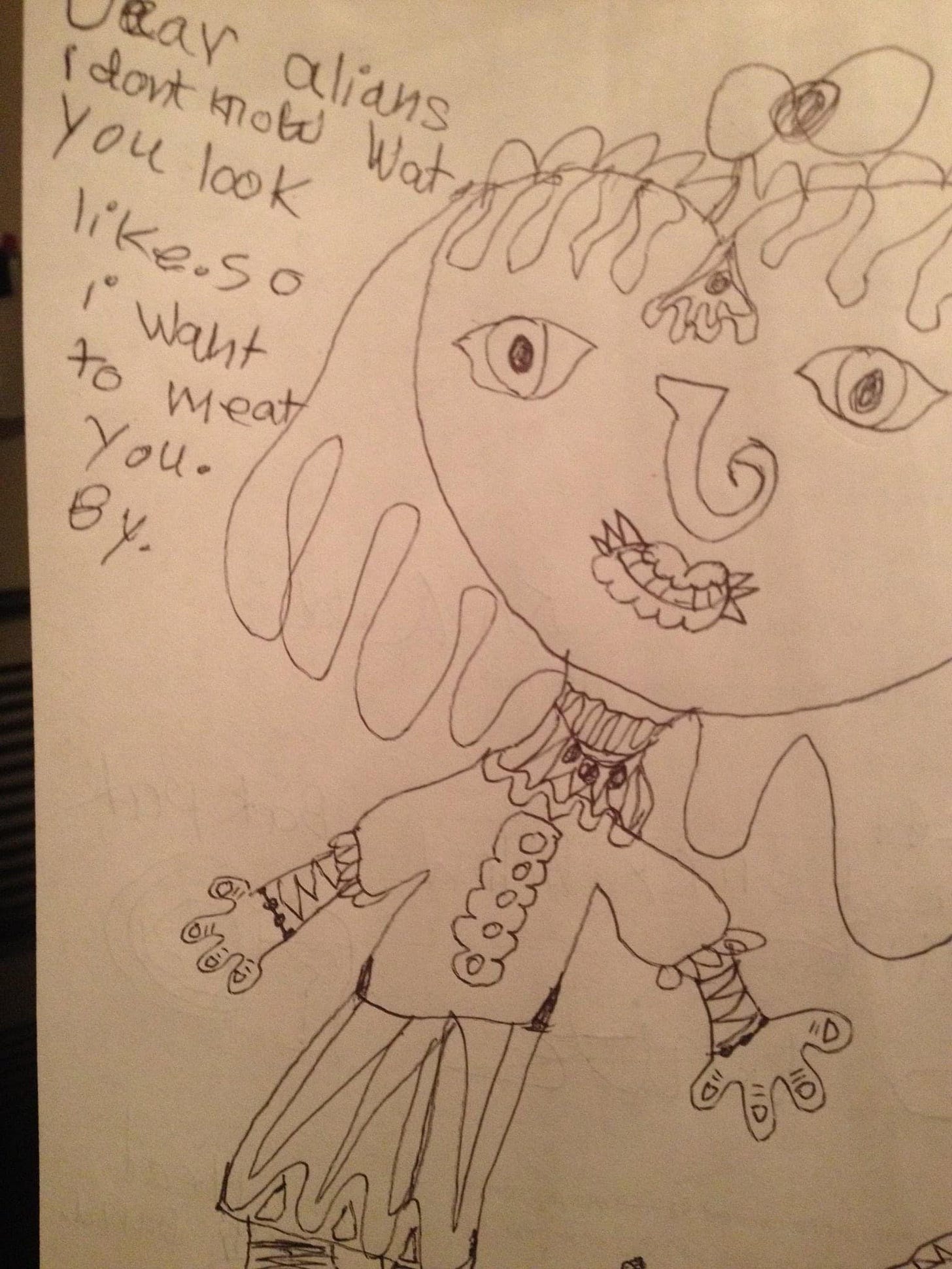

Apparently the attraction to all-things-alien in my household is genetic or just seeped socially from me to my girls, who started producing odd art like this (from my daughter at the age of 7):

This drawing delights me because this is no monster my child depicts but rather something uniquely beautiful. She renders this alien, of impeccable fashion and detailing, as not a thing for revulsion but curiosity. A lacy entity she’d like to “meat”—if you can forgive the kid-spelling. But that error is telling too: she loved hamburgers so much in this era predating her current vegetarianism, that she would refer to actual cows in fields as “beef.” There’s a meme kicking around that says maybe humans fear alien life because we worry they might treat humans the same way we treat the other species on earth, namely: not so well.

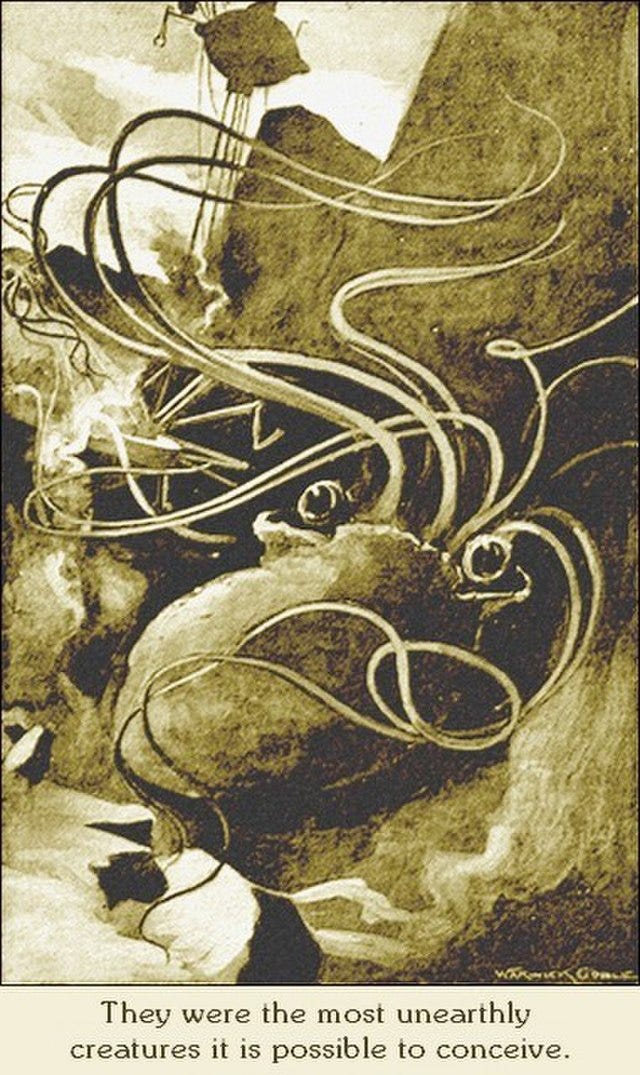

Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.

— H. G. Wells (1898), The War of the Worlds

Since the “The War of the Worlds” radio show panic of 1938 when listeners didn’t know the high-pitched news of the Martian invasion narrated was fiction based on the 1898 book by H.G. Wells—with malicious aliens coming for our resources and resembling fat octopi—and the massive pile of wildly divergent popular culture depictions in all mediums since, the supposed citizen-claimed sightings through the decades have somehow naturally morphed into a more agreeable creature that looks like a petite, bald, emaciated elderly/child human with big eyes, a possible case of macrocephaly, and no apparent offending gender parts.

From my writing on Travis Walton’s abduction last time, “he describes easily fighting the aliens back with a beaker. They weren’t prepared for any combat or confrontation and were quite passive. There were a few human-looking aliens who put a mask on him. The others more typically ‘alien’ in appearance were hairless and small with huge eyes, grayish white skin, 3-4’ in height, and wearing, somewhat humorously, orange-brown overalls.”

Being humans, we see ourselves in everything, even our aliens. Or maybe they come to us in these humanlike guises so we’ll calm down a bit. They typically resemble us, if in the buff, so it’s nice that Travis put them in a little outfit for modesty. How they turned blue somewhere along the way no one knows—maybe by holding their other-atmosphered breaths.

Harvard evolutionary biologist Jonathan Losos considers our tendency to anthropomorphize our aliens in the NPR piece of 2017, Would Aliens Look Like Us? Science, like popular culture, diverges on the answer of what these many possible earth-like planets in the universe might hold.

But what would those life forms be like?

If we’re to believe Hollywood, quite a lot like life here on Earth. From Star Trek to Star Wars to Valerian and beyond, most interplanetary science-fiction movies populate their worlds with lifeforms quite similar—in general appearance and biology—to what has evolved here on Planet Earth. Guardians of the Galaxy takes this approach to a new extreme, including Groot, a humanoid evolved from a botanical ancestor (perhaps explaining its limited vocabulary).

Yet, not all films agree. Last year’s Arrival introduced heptapods, organisms with seemingly little affinity to any species here on the home planet.

So, what should we expect? An Avatar-like ecosystem full of species slightly different from those on Earth, or a world composed of unfamiliar organisms?

The great astronomer Carl Sagan was in Arrival’s camp, proclaiming “extraterrestrials would be very different from us.” Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould expressed similar sentiments, but felt that there was no way to scientifically study the question other than finding life on another planet.

But there is “convergent evolution” to consider—and how species often seem to independently evolve similarly such as “fast-swimming marine predators: dolphins, sharks, tuna and ichthyosaurs (extinct marine reptiles from the Age of the Dinosaurs),” or “Euphorbia plants from dry parts of Africa. Tough-skinned, often green, with spines instead of leaves, they look like cacti, but they’'re not.” And to counter the many more examples of this that may lead one to believe evolution is inevitable, deterministic, and repeatable—like the antihero of the poem I once wrote who blew up the earth and its contents only to have it re-evolve eons later into exactly what it was originally—are all the equal and opposite occasions when it just isn’t.

Although the list of examples of convergence is impressive, it wouldn’t be hard to make an equally impressive list of non-convergence. Off the top of my head, here are some evolutionary singletons, types of animals that have evolved just once, without a close match: sauropod dinosaurs; elephants; the kiwi; sloths; and the world’s greatest animal, the duck-billed platypus. Each of these types of animals has evolved a single time, with no close evolutionary match, now or ever.

It seems that instead of being able to come up with any easy answer to anything, evolution has infinite ways to solve a problem, and all of them are correct. It just depends. And, in conclusion, according to Losos, the more “alien” depictions of aliens are likely more probable than the perhaps more palatable humanized ones.

Closely-related species (or populations of the same species) tend to adapt in the same way, not surprisingly because they start out so similar in so many ways—natural selection is likely to modify them in similar ways. By contrast, distantly-related species, initially different in so many attributes, are much more likely to find different ways to adapt to the same situation. Think about the difference between birds and mammals: The former have beaks, the latter teeth and fingers. It’s not surprising that woodpeckers and aye-ayes found different ways to solve the same problem.

Of course, life couldn’t be more distantly related than if it occurred on another planet. With all the differences that such life forms must exhibit, natural selection (if it occurred—who’s to say that evolutionary processes would be the same?) might very well sculpt well-adapted species, but they wouldn’t look at all like us and our earthly compatriots. The aye-aye and the kiwi tell us that. And that means that the minority opinion in Hollywood is almost surely correct.

If you want to think about what extraterrestrial life might be like, watch Arrival, not Avatar or Guardians of the Galaxy.

I loved the edition of National Geographic Kids magazine my household received and poured over in 2014, with centerfold renderings from illustrator David Aguilar’s Alien Worlds book, depicting what aliens might look like smartly based on their differing planetary conditions.

It is time that we drop Hollywood’s humanoid view of extraterrestrials. In reality, David Aguilar says, “We are going to find bizarre adaptations.”

Aguilar’s creations include inventive, but scientifically plausible, creatures like crustaceans who inflate giant airbags around themselves to handle massive gravity waves 60 feet tall; ice fishers on a frozen planet who extend long barbed tongues through the sheaths; coneheads with eyes perched high on extensions all the better to peer through all the clouds of their steamy planet; cave crawlers where it’s so hot they have to hide underground; windcatchers (see above) with giant wings that float their turbulent climate like kites for weeks on end; ghastly undersea freaks of a melted planet; tentacled beasts that cling to rocks and have infrared spectrum-detecting eyes for their red dwarf star conditions; an awful worm with spikes for a planet of low gravitational pull.

With aliens so potentially wild yet well-adapted, I have to wonder about a few things here on humans that don’t make as much sense. Male nipples, tailbones, wisdom teeth, the appendix, and other vestigial organs that should have evolved away long ago. Science is weird, and so are we, especially for sometimes assuming we’re not.

This stuff is so much fun. You may know of the classic old Twilight Zone episode, To Serve Man, where aliens come to earth and solve all our problems (food, disease), and all looks really peachy (I'm piecing this together from memory) but at the last moment as our scientist protagonist is walking up the gangplank to visit the alien's world, his assistant who'd been trying to translate the alien book they'd gotten hold of, "To Serve Man," runs up telling him to run because she'd just figured out [SPOILER ALERT] that *it was a cook book*! The protagonist tries to break line but the aliens push him aboard. Good eating! Any Twilight Zone nerds out there feel free to correct any details.

This is offline but you might find it interesting - from Tobe Hooper who directed Poltergeist and Texas Chain Saw Massacre, a sexy alien movie called Lifeforce that came out in 1985 (a great era for pulp/drive-in movies) about space vampires where a beautiful, constantly naked young woman moves from man to man like a succubus, draining his lifeforce, and turning him into a space vampire too. Here's a trailer. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpTNBFbYqUI

This is also making me remember a video I recently saw about how amazingly intelligent octopuses are, saying how they seemed to develop along a different track that any of our more familiar critters/relatives. It makes sense that a lot of aliens look octoputic, when they don't look humanoid.

I like the alien depiction in Galaxy Quest, The Abyss, and also Contact - they used a comforting figure from the mind of the traveler to communicate with them. I love the movie Arrival. It’s one of my all time favorite movies.