The curriculum of my high school physics class involved the teacher playing Beatles records backward (“turn me on, dead man”), helping us find subliminal (and overt) sexual messages in magazine ads for cigarettes, and repeatedly telling us that all the alien sightings people report are hogwash. “If there are other life forms with the technology to travel that far to us, they would also have the means to just call.” His point resonated—and though we were never doing any actual physics, arguably I learned the most in his class and it remains to this day the most memorable of my education. It makes sense: traversing galaxies across the universe is massively inefficient; if extraterrestrial life forms have reached that advanced stage of development, they would certainly also have the means to just communicate with us directly by radio signals or whatever best cuts through our dense human white noise.

Arrival, the 2016 quietly intellectual sci-fi drama from Denis Villeneuve, doesn’t take sides in my physics teacher’s 35-year-old argument but rather has the aliens doing both—traveling and communicating—in wholly unique ways for these sort of movies. With not one but 12 upright oval ships (of Brancusi-level sculptural quality) suddenly hovering above the ground in different sites around the globe, each country establishes emergency teams in a race to decipher the language and its mysterious messages before who-knows-what could happen. (Despite the world’s accumulating panic, I felt weirdly at peace and no sense of threat in this film because—similar to my physics teacher’s argument—if they came to wage war, they also wouldn’t have had to play nicely dilly-dallying so long with linguistic experts in order to do that. It’s also worth noting that the screenwriter Eric Heisserer adapted the script from the short story “Understand” by author Ted Chiang, in which the aliens don’t actually bother transporting themselves here but rather just seed all these screens around earth so we can effectively FaceTime instead.)

Discounting the inefficiencies of space travel x 12 ships (or perhaps with their uber-advanced tech the dirty dozen leapt here quantumly?), Arrival had me fascinated the first time I saw it a few years ago and even more the second time now when it propelled me to research and learn further. It’s one of those movies that you might want to start again as soon as you finish. Which would be an appropriate repetitive action for a story that goes in a loop about decoding communication that comes in a circle and contains all time forward and back.

Circles are essential in the movie, and they’ve shaped my recent history, so much so that I have a big neon red one over my bed.

From Space.com:

Circles are a very important, recurring theme in Arrival. The story explores the nature of time as a circle, and circles appear in many places throughout the film—for example, a hospital where two crucial events take place in the movie has a circular layout. Villeneuve wanted the aliens’ written language to be based on circles...

The circle language they created for the film is so beautiful it shocks you the first time a tentacled creature in mist behind glass spits out a flourish as if in a swirl of undersea octopus ink. Interestingly, like Chinese, the sound of the language bears no resemblance to its visual. While we in English sound out our written syllables, the alien noises lie on a separate plane from their so-called logograms. A clip on the first word it emits, human:

My ex texted me recently to ask, had I seen Arrival—the alien language is tattooed on my arm! Indeed, my logo from my bar, the defunct “make your mark @” Stain Arts Lounge of 2004-2009, meant to convey the ring of wine left on a napkin under a wine glass (and roughly outlined by the red neon above which used to shine from my plate glass storefront), could pretty easily morph into one of these logograms. I’ve never been thrilled with this tattoo since I got it done in quick-and-dirty fashion in New Orleans from whichever shop happened to be down the block from the former orphanage where I wrote the business plan before returning home to sign the lease. I didn’t think through the dimensions at the time—it was too small to resemble the base of a good glass—and the tattoo never read quite right on my arm. Suddenly I’m inspired to make the old thing new again. Reform the shape that rings the scar of my once-removed birthmark into this inky swirl of a curious foreign creature rendering its amazing take on “human.” Coming full circle to link my history—birth to bar—to a future I dream of, in which we find other life out there to learn from through our space exploration and investigation.

The movie, among its many levels, offers deep exploration of what it takes to comprehend a new language. Field scientists study patterns to see what repetitive clues emerge first, the same way I learned French by listening to a three-year-old in Belgium. His age and own rudimentary sense of his native language helped me quickly understand the key phrases one needed to live (help, stop, eat, no, more, sleep, etc.) and soon, following the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis the movie plays with, I was dreaming in French and the French seemed to be changing my brain. My thoughts in English were emerging Frenchified. (“It is good the bread, no?”). The first French dream woke me up with a start and I’ll never forget its sentence: “Quelqu’un a volé mon vélo” (someone stole my bicycle.)

How we might piece together an alien tongue is the same way a linguist might land in a remote tribe and try to decode them syllable by syllable; or maybe even how a biologist might decipher the sounds of a dolphin or whale.

From Space.com:

Seth Shostak, a scientist at the SETI Institute (SETI stands for search for extraterrestrial intelligence), said some scientists have thought about how humans might translate alien languages. Linguists have shown that there are many redundancies in human languages, which is part of how we are able to comprehend spoken languages at all, Shostak said. For example, studies have shown that if all the vowels are removed from a written document, a person (who has never seen the document in its complete form) can still read most of the words.

“It turns out there’s a mathematical law for the redundancy of any language,” Shostak said. “And you can apply that to the sounds made by dolphins or even other critters, like ants. And they follow this same mathematical law. So that suggests that it’s not just noise [the animals are making], there’s actually a language there. So I think that if you picked up a signal coming from aliens, you’d do the same thing.”

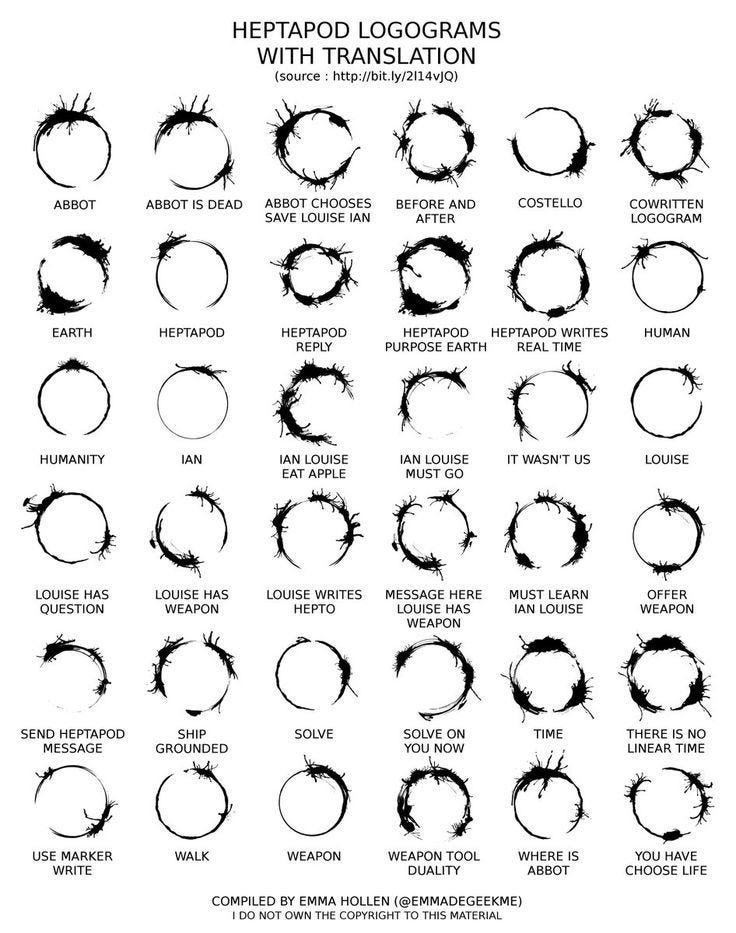

These aliens (“Heptapods”) in Arrival throw out their sentences all once into logogram symbols with no hierarchy and no timeline. So instead of a sentence with a structure and a storyline, it’s more of a word cloud emitted all at the same level at once. The way language with no timeline might change your brain if you learn it, in the world of this film, is you might now be able to cycle in any direction at all, forward to the future or back to the past, all contained in the present. So our protagonist linguist flashes back to images of her daughter who hasn’t been born yet, whose father she is only now just meeting, or maybe it’s in the past and they remember—unclear. They developed not a complete exhaustive lexicon for the movie but about 100 circular images, each dense with many words and meanings as the circles have tendrils that can take you anywhere. The film’s production designer Patrice Vermette conjured the concept that his wife artist Martine Bertrand quickly and elegantly realized with the visuals.

“We wanted to have something that was aesthetically pleasing, and that [viewers] could not at first know that it’s a language or not,” Vermette said.

Bertrand, who was also at the news conference, is Vermette’s wife. He says she offered to take a shot at designing the language symbols, and it took her only a day to come up with something similar to the finished product. Vermette said Bertrand’s solution seemed so obvious once she showed it to them. (“I felt very stupid not to have asked her before,” he said.)

The symbols all start with a black circle, which then has loose tendrils and splotches branching out from the solid ring. The splotches look as though they were made by hand using an ink pen. The aliens in the movie squirt the ink out of their bodies, sort of like a squid or an octopus.)

In the film, the scientists discover that the circles typically represent a full statement, but the statement can be broken up into words. The protagonists eventually create an index of these inky words, so they can write messages to the aliens. In reality, Vermette said he and Villeneuve had their own index of about 100 alien words made in the style that Bertrand designed. As the project moved forward, the pair consulted with real-world linguists and archaeologists to help refine the design.

Have there been such circular languages? Apparently not but there are ideograms (or icons) through the ages and across languages that don’t seem to change much between the ancients and us, as this author posits, and therefore also transcend time. Word pictures that convey a horse, woman, wheel that look the same between the Minoans and moderns. (Although I’d argue these images take a shorthand approach to simply depict how their counterparts in real life look, and still look, to this day, so it’s not the same as conveying abstract ideas in seemingly arbitrary flourishes the way Arrival does). A similarly geeky take on this comes from the LA Times that interviewed Jessica Coon, McGill University associate professor in syntax and indigenous languages, who consulted on the movie and teaches us (as if we’re aliens) words like ergativity, morphology, and nominalization. “Non-linear orthography” includes such logograms that transcend structure and order and therefore live outside of time, or contain all time.

Rendered in high-def here with each phase/word from the movie in a separate file (perfect for me to bring to a tattoo shop) and compiled here in a handy chart by Emma Hollen, the logograms:

From the LA Times: “It felt like a great challenge to us—portraying what would they communicate,” said Dan Levine, one of the film’s producers. “We wanted this language to be scary yet beautiful, and also linguistically correct.”

Combining scary yet beautiful makes for my idea of a perfect movie. The words revealed in the movie that put earthlings into a nervous bomb-prone tizzy are “offer weapon” and other iterations of “weapon” that the linguist soon realizes is referring to nothing but the tool of language, threatening and divisive if mishandled and lovely if used to connect us as intended.

Fascinating. As an aside, it wasn't until over a year after Scooter my parrot died and I was researching pet-loss grief and parrot intelligence that I understood he'd named me - two short whistled at a particular pitch, which meant "me" (it also meant "call back" - he was saying my bird name and I was supposed to respond accordingly, like birds do). Recent studies demonstrated that parrot parents give their babies a name similar to, but distinctive from, either of the parents. This becomes their "contact signature call" that is both a name and an announcement of presence. Also a greeting - as when Scooter would yell out "Hey Scooter" (this is what I accidentally named him because I said it over and over) to the grackles as we passed by. He loved the grackles.

Love SciFi. Loved Arrival. We just watched it a few weeks ago so everything was so fresh. To me, the most poignant plot line was about Dr Banks choosing to have a daughter even though she knew the cost but instead choosing to celebrate love and life.