I don’t drink enough to merit committing to Dry January. But for those who did and are moments away from a celebratory toast, congrats, and might I offer some glögg, gløgg, or grog with a garnish of etymology and history?

Bar, Not Bar

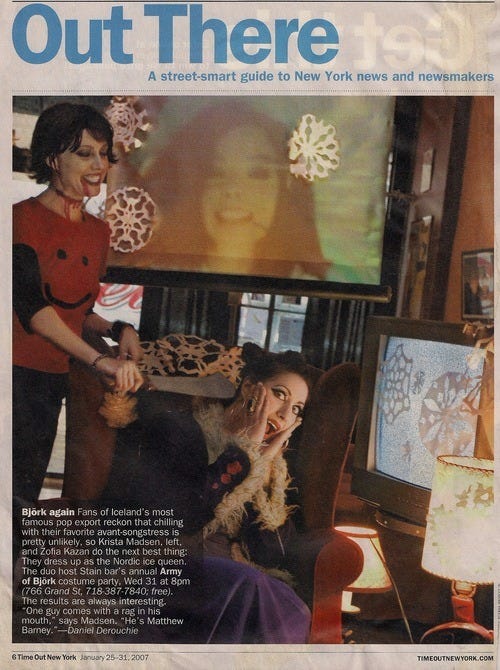

My personal history with the glogg with an umlaut or a slash through its o (letter formats that have no actual name) depending on what country you’re in from Sweden to Iceland, started in the early 2000s when I owned a bar that served not only just wine and beer, but an even nichier subset of that—just wine and beer from New York State. Plus, I was quick to correct, it’s not a drunken sort of bar but an “arts lounge,” mind you, and one mainly fueled on creative daily events and theme parties. I loved Halloween so much, we effectively had it all year: any month that had 31 days had a different costume party. I annually filled the sad ends of January with a Björk-inspired romp that featured bowls of sugarcubes to suck on (the name of her original band), her music videos projected, and $5 mugs of mulled wine or glogg to drink. I can’t even fathom now how I pulled this off without social media (then it was solely MySpace, where I found bands but not necessarily promoted their actual playing). It was mainly a mix of having the good fortune to be featured often in Time Out magazine…and growing a good old timey newsletter following. Cheers to newsletters! It was a giddy age sprinkled with grief. I remember the club kid who cried when he realized the whack songstress herself wasn’t coming, and couldn’t be consoled by the sugarcube I handed him.

As a bar owner, I was an industry anomaly: I didn’t drink much and preferred going to bed early. This came intentionally after definite periods of my life where I did drink too much and had a whole series of (typically romantic) regrets, so it was important to me to have a bar that wasn’t alcohol-focused. I think I succeeded at that, if not with the most obvious business model financially. In my more recent history, I boast having had a recovering addict boyfriend (I actually recommend it). Alcohol was never his problem and he didn’t mind, having worked through all the steps, if I drank. Instead I followed his lead and enjoyed a two-year period where it just never came into play and I didn’t miss the absence. It was liberating, empowering even—and cheaper—to have a dry relationship based on anything but alcoholic consumption.

Which brings us to Dry January. Dry January, according to this Time Magazine piece, started in 2013 with the Alcohol Change UK org which later trademarked the annual campaign to stop alcohol consumption for the month, “though the practice has roots that extend as far back as 1942, when Finland had their own ‘Sober January’ to help in the war against the Soviet Union.” Now, as alcohol consumption surges along with social media, the popularity of—and the need for—this campaign seems to be growing each year and peaked in the pandemic. The article cites 15% of US adults—upwards of 260 million—pledging to practice Dry January in 2023, against the backdrop of stats such as drinking increasing by 75% in the span of 1990-2017.

The benefits of putting a stop-gap to this are most obviously health-related but also financial.

While Dry January only lasts a month, research shows that a reprieve from alcohol can help moderate to heavy drinkers see immediate benefits including weight loss, better diet, and a reduction in liver fat and blood sugar. A University of Sussex survey found that 71% of people that took part in Dry January say they slept better, nearly the same amount said they had more energy. Participating may also be especially beneficial to women, who can suffer greater health and safety risks when they drink because their bodies take longer to break alcohol down, according to a UC Davis health report.

Research shows that reduced intake of alcohol for moderate and heavy drinkers has broader health benefits, like better health and liver health. Six months after adults completed Dry January, participants reported drinking an average of one day less per week, according to a 2016 study published in a journal of the American Psychological Association.

There are also financial benefits; 88% of participants in a University of Sussex survey conducted in 2018 say they saved money while not drinking.

The hope is a temporary clean slate might lead to less drinking ongoing with some new better habits gaining momentum in the interim. But ’tis a dark, cold (typically!) time, these doldrums of winter when the resolutions quickly fade and get replaced by slogging through salted roadslush and grim holiday-less nights. Even I, who verges on teetotaler, have cravings for a warm adult beverage in a satisfying mug. A splash of rum in hot cocoa, or mulled wine nicely spiced.

G Drinks

This “glögg, grog” post on the Sesquiotica blog gets into the etymology of these g drinks. Glögg, or mulled wine, is “from the Swedish verb glödga, ‘make hot, mull’; in Norwegian and Danish, it’s spelled gløgg, because they use ø instead of ö.” (Not to be confused with German Glühwein which grows from the German word for “glow.”) And grog, which started as watered down rum. Writer James Sharbeck continues:

After a few slugs of glögg you may feel a bit groggy. But while glögg is spicy and alcoholic and so is grog (well, maybe citrusy and alcoholic), there is no etymological connection. Grog, which is (or originally was—it can refer to a lot of things now) a mixture of rum with water or weak beer and lemon or lime juice, was introduced into the Royal Navy (in place of straight rum) by Vice Admiral Edward Vernon, who was called Old Grog, or Old Grogram, because he wore a grogram coat. Grogram is an English version of the French gros-grain, which means ‘large grain’ and names a kind of cloth that has a ribbed pattern, the sort of thing often used on ribbons for medals these days. Anyway, groggy meaning ‘sleepy, dazed, intoxicated’ comes from grog because obviously if you’ve had a lot you are. Or, if you’ve had glögg, you could be glöggy, I guess.

So glögg. Grog. Glug. Don’t forget eggnog. Which is seasoned with nutmeg. Beer is beer but comes in a keg or jug. There seems to be a theme of g words sticking when it comes to naming beverages.

I also see many recipes connecting Glüh for glow with their assertion that Glögg means “glowing ember,” so maybe there’s something to the glowing after all.

Let’s make some!

This version of warmed Grog on Food.com sounds more appealing than the original with its apple juice, honey, cloves, ginger and cinnamon with rum:

Ingredients

2 ounces dark rum

3 ounces apple juice

1 lime, juice of

1 teaspoon honey or 1 teaspoon brown sugar

2 whole cloves

1 slice fresh ginger, thin slice

1 small cinnamon stick

Directions

Add all of the ingredients to a small saucepan and heat gently to dissolve the honey.

When hot, strain into a heatproof mug.

Similarly festive and boozy, is this traditional Swedish Glögg recipe from Bonappetit.com. And if you’re feeling wild, some other recipes involve setting your drink on fire.

Ingredients

Makes about 1½ quarts

2 cinnamon sticks, broken into pieces

1 tsp. cardamom pods

1 small piece ginger, peeled

Zest of ½ orange

6 whole cloves

½ cup vodka

1 750-ml bottle dry red wine

1 cup ruby port or Madeira

1 cup granulated sugar

1 Tbsp. vanilla sugar

½ cup blanched whole almonds

½ cup dark raisins

Directions

Crush cinnamon and cardamom in a mortar and pestle (or put them on a cutting board and crush with the bottom of a heavy pot.) Transfer to a small glass jar and add ginger, orange zest, cloves, and vodka. Let sit 1 day.

Strain vodka through a fine-mesh sieve into a large saucepan; discard spices. Add wine, port, granulated sugar, vanilla sugar, almonds, and raisins and heat over medium just until bubbles start to form around the edges.

Ladle glögg into mugs, with a few almonds and raisins in each one. Keep any remaining glögg warm over very low heat until ready to serve (do not let it boil).

The Hangover

Finally, we come to groggy, which is first found in use in 1770, according to etymonline.com, as “drunk, overcome with grog so as to stagger or stumble.” Non-alcoholic meaning of “shaky, tottering” is from 1832, originally from the fight ring. Also used for “hobbled horses” (1828).

Now it’s more dazed and confused in usage. Stunned, unsteady, lethargic from illness, lack of sleep, drink, suffering blows.

Grog from the stingy admiral Vernon in his grogram came in 1740. “Eventually the word came popularly to mean ‘strong drink’ of any kind. Grog shop, a ‘tavern where alcohol is sold by the glass,’ is from 1790.”

And fun fact: “George Washington’s older half-brother Lawrence served under Vernon in the Caribbean and renamed the family’s Hunting Creek Plantation in Virginia for him in 1740, calling it Mount Vernon.”

Our history is steeped in the sauce, however diluted it may be. But with those stats that show how dramatically drinking is on the rise of late, then maybe hand in hand goes the groggy. Behold this chart and the usage of the word on a sharp incline from 1980 on:

I get tired just looking at it, and sunnily sip my OJ with seltzer.

Don't forget the kids today and their "borg"! Aka "blackout rage gallon." There really is something about this boozy g! https://ginraiders.com/article/what-is-a-borg-drink-titktok-gen-z/

STAIN! Wish I'd gotten to one of your Bjork events. (Loved the story about the sad club kid.) I love/d her!