There have been times in my writing life—memorable, magical, rare—when the words just seemed to flow from my fingertips.

Writing, for me, isn’t a brain exercise so much as some alchemy that happens between hands and keyboard, since that’s been my main medium from the early word processor/typewriter hybrids in high school to those cute Mac Classics in college and all the Apples ever since. I get plenty of ideas when I step away—run, shower, walk in the woods—and the mind has to be primed, but the real sentences come only during and from this physical act. It can be on paper, but that’s more reserved for thoughts, bad poetry, notes, journaling, lists. The screen is the ultimate blank page, unlined, unlimited space for the wane and wax of the constant cut-and-paste, spastic rearranging, and forever-editing. Computers have inextricably informed how I think and how I write.

There was the time sophomore year in college when I had developed a severe watered-down cafeteria fountain soda version of a Diet Coke addiction. When I bought a real 2L bottle of it one night from the corner Wawa market in order to write an English paper due the next day, the heightened caffeine took me to another mental state where it became possible to write one bad paper, and then another, and then another, and then suddenly, around 3 am to hit this zone where I knew it was now good and “it was as if god were talking through my fingers,” I announced to someone, crazy-eyed in the morning. I knew it was a solid paper—fun and weird, and stereotypically collegiate in the way that I was talking about liminal spaces in Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood and how the most interesting things in life are in the cracks, or in the graffiti on the toilet stall, or actually getting flushed—and to my delight it won that professor’s informal Southern Literature essay prize.

The other time I rode such a state of caffeine-plus-predawn fugue was when I was finishing my second novel, Four Corners. I am not a night person, but I made this romantic decision that I’d stay up until I was done really going through this book for good before launching it off to my publisher in West Alabama. I lived in Brooklyn, at the intersection of the J train and Bushwick-Bed-Stuy-Williamsburg. I have to write in front of a window, a room with a view. So I had myself positioned looking out the second floor window of this odd pink house squatting amidst the projects, overlooking McDonald’s and the WoodHull Hospital. In the middle of the night, on whatever cup of coffee, I reached the point where the work suddenly converted from drudgery to joy. It was like I was a master surgeon now who had done this procedure a 1,000 times and it became muscle memory—expertly snipping, shaping, suturing. Art of the operation. Or I thought of it as weaving the various different color threads of recurring themes and images through the book. It was all connecting, tightening, making sense. I could see the tapestry; it was good. And as the sun came up, I felt giddily compelled to snap a photo to mark this moment.

And then there are all the other times—much more typical and often—when writing feels like childbirth, my first birth, where the baby didn’t want to emerge and it really freaking hurt.

Writing is a whacky pursuit to have crafted my entire life around. The dream can more often be a nightmare! There’s no fantasy in sitting chained to a chair in a drafty winter house in a heavy robe for hours on end. Sometimes when faced with the pressure and pain of this, I find myself doing anything but—suddenly compelled to scour the microwave, research irrelevant tangential topics online, configure yet another comfort food snack.

Sometimes for me, writer’s block is a just a pouty feeling of “I don’t want to” and stomping off to do anything else.

Sometimes the writer’s block has lasted an entire decade, when “I don’t want to” was just “I can’t.” I had babies, who grew into small kids with their own words, and many jobs (that also demanded writing), so I couldn’t possibly find the time/brain power to insert another Novel into that. So just the idea of it and some early pages festered like an old wound, taunting me from a great distance, or entirely lost.

Sometimes writer’s block can mean the “blocking” sort of martial arts maneuver required to protect your space and time to make the dark magic happen. My husband asked where I wanted to go as a family for my 40th birthday. I said, I want to go alone to a nearby cheap hotel and just work on that book already, which is the first and last time I did that for many years.

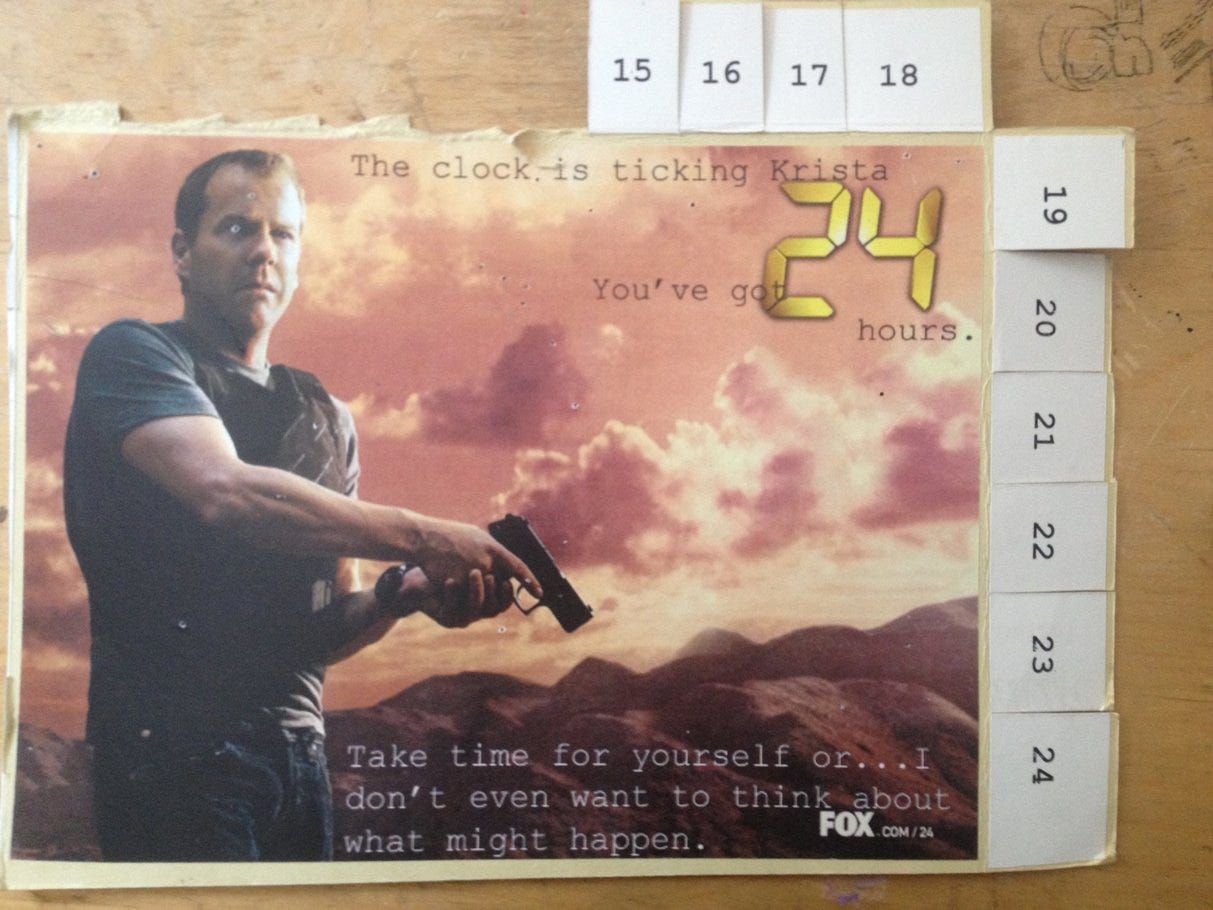

Wherever and however you live, there is so much for you as a writer, so much that demands you pay attention, and in turn so much to shut out, block out. This a constant struggle I face, how to juggle living a life with taking the time to write about life. If you’re like me, this requires the impossible challenge of being both a hermit for weeks on end alternated with engagement with the world, learning and experiencing as much and as diversely as you possibly can. Balance is key, and I honestly hadn’t found it until creating the self-induced deadline of committing to a regular weekly newsletter here.

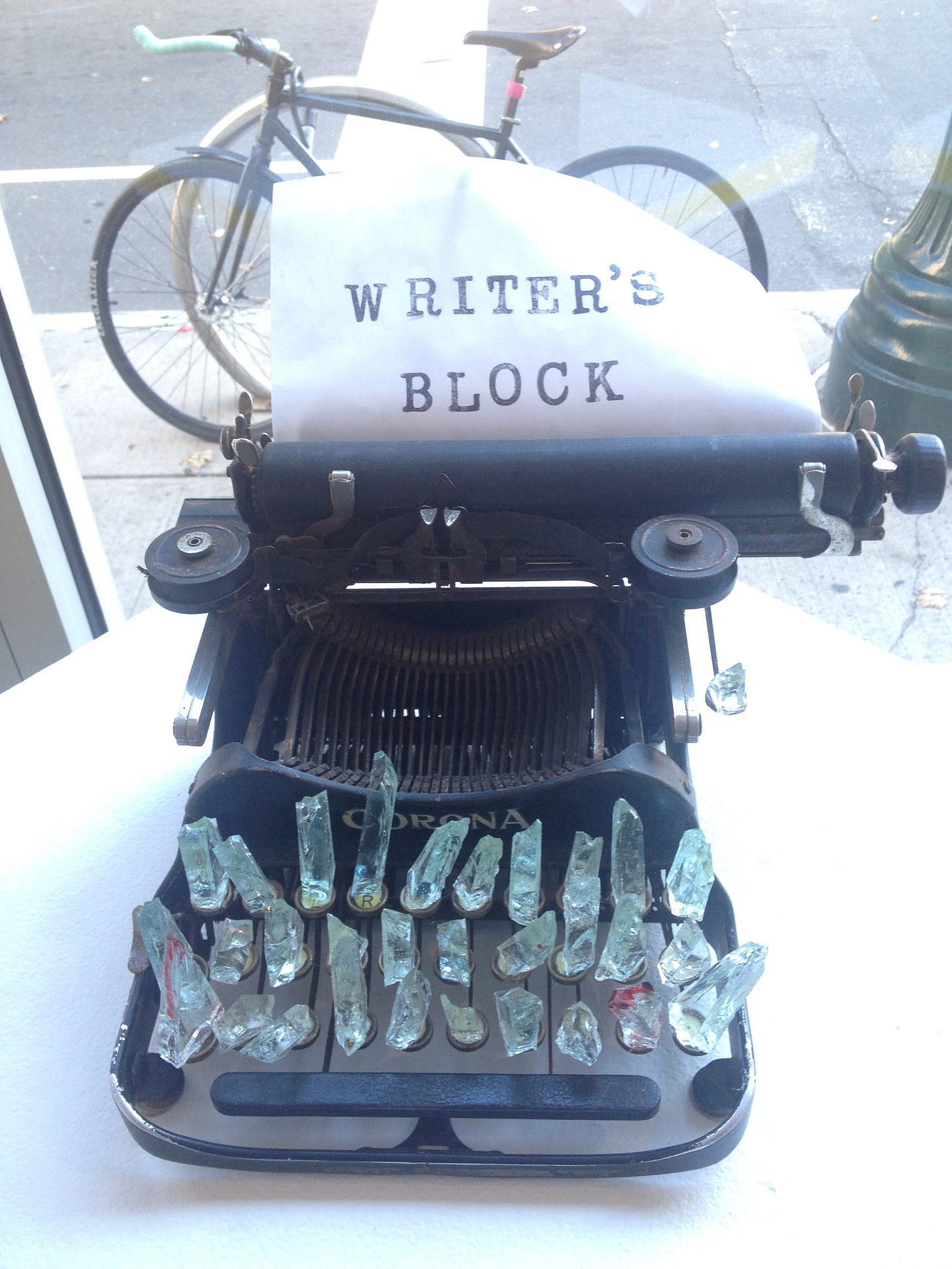

Writer’s block can also mean literally creating the slab of clay required first in order to begin forming something amazing.

I once told my creative writing students at NYU that writing was like sculpting. Only a writer has to actually make the clay first so we have something to sculpt with. The initial work is getting anything down and then the “real” work is crafting that into something worthwhile, the editing. You can draft your work endlessly; in time it might become drafty and full of air, with ever more room for you and your reader to breathe and make new connections and discoveries. Both of you should be surprised at the outcome.

Author Jodi Picoult on how she deals with writer’s block:

I don’t. Writer’s block is for people who have the luxury of time; I started writing when I had three kids under the age of four. I used to write every ten minutes I got to sit in front of a computer. Now, when I have more time, I function the same way: if it’s writing time, I write. I may write garbage, but you can always edit garbage. You can’t edit a blank page.

The difficulty of beginning in any task or art form is simply beginning, facing that blank page I wrote about in recent weeks, leaning into the silence. So decide to begin and the inertia shifts from inaction to action and builds. First drafts by nature are thoughtless; Ernest Hemingway said the first draft of anything is “shit.” He did countless drafts. Just get it down. Confidence builds with momentum, knowing you can always go back to fix it. As long as the “it” exists.

But sometimes there really is a block, in the standard way this term writer’s block was intended. Any honest discussion on writing has to face those times when you just can’t do it. Perhaps, as some think, writer’s block is a myth, an excuse, a privilege, or maybe it’s just a necessary part of this process, forcing us to pause and get offline and reenter the world for a while. Whatever it is, being blocked needn’t paralyze you for good. It’s a sign to refuel, regroup, move. I am inspired during a jog to the river, at an art gallery, a concert, in the shower when somehow the brain loosens and can reenter the work anew.

Here’s a chorus of hope and advice from successful writers who have suffered, survived, and thrived in spite of, or because of, their blocks:

Nina Schuyler: “One terrific benefit of having a child is that you don’t suffer from writer’s block. Writer’s block is a phenomenon for those with ample time and a proclivity for channeling the voice of their high school teacher who said they’d never ever be a writer.”

Lewis Buzbee: “I write. Anything. Sentences, paragraphs, descriptions of the street, passing strangers. V.S. Pritchett said, ‘Invention invents itself.’ I believe that.”

Max Apple: “The things that block a writer are not the lack of words, but the same things that block all people—the difficulties of life. If I’m stuck in the midst of a story I take a nap. It often works and if it doesn’t, I still feel better.”

Dan Chaon: “I usually have more than one thing I’m working on at once—I’ve been working on three different novels. When I get stuck on one, I hop back and forth. It’s sort of freeing: I can say I’m abandoning this thing that I hate forever and I’m moving on to something that’s good. I’ll find that I’ll go back to [the other project] in a day or a week and like it again. But that moment of wanting to trash something—that Virginia Woolf moment when you have to be stopped from filling your pocket with stones—comes pretty regularly for me. Switching is probably a good thing.”

Scott Turow: “Re-reading what I’ve already written will almost always do the trick. If nothing else, I can rewrite. More often, I’ll find that what’s there sparks other ideas.”

Michael Cunningham: “Every writer I know suffers periodically from, if not actual writer’s block, spells during which the inspiration seems to evaporate. If I’m steady in my habits, I’m extremely erratic in this other, more slippery realm. My day-to-day discipline is, really, my way of compensating for the unreliability of my own access to whatever it is that drives the writerly engine. One day, I feel so confident and full of ideas and language that I can barely keep up with myself. The next, it’s all I can do to write one lame, unconvincing sentence.

When I was younger, I became obsessed with trying to chart my good days and my bad. Was it related to sleep, diet, sex? I tried all kinds of variations, with the grim purpose of youth. Celibacy the day before a writing day? I’ll give it a try. What about sugar, caffeine, alcohol? More, or less, of each, and in what quantities? Many trials were conducted. Needless to say, those experiments led me nowhere. It is, it seems, purely and simply a mystery, the coming and going of one’s gift.

So I show up every day, and do the best I can. I’ve been known to write ten pages or more on a good day. On the bad days, I still force myself to write SOMETHING, even if it’s one limp, sad little line that will surely be deleted tomorrow.

Here’s the funny thing—a month or so later, I can’t tell what I wrote on the ecstatic days from what I wrote on the wrenching ones. The lines that seemed so good when I wrote them turn out, later on, to be neither better nor worse than the ones I squeezed out with my fingers pinching my nose against the stink of mediocrity.

All I can think, then, is this: Wherever inspiration comes from, it comes constantly, and what varies from day to day and week to week is our access to it. So I go on. I fasten my seat belt. I do my best to have faith.”

M.T. Anderson: “Sometimes it’s helpful to analyze what’s wrong, to ask why it is that I don’t feel enthusiastic about what has to happen next. I ask myself if I can skip over the part that I appear to dread. I ask myself if perhaps there’s another angle I could take, or if there’s some detail that might reinvest the situation with interest for me.

Sometimes a random infusion of fact helps, so I go read about a topic about which I know nothing (there are a lot of them) and see if anything floats to the surface. I don’t know what I’m looking for, but I know when I find it.

Sometimes reading other writers helps. You learn some little technique that turns out to be useful, or simply are reinspired by the amazing things others do.

And sometimes there’s nothing for it but forgetting about the project for a while and letting the brain mulch. I watch a movie, or go out for a walk. Or I take days off, or months, and write something else entirely. I switch between books—one light and comic, the other dark and heavy, for example. As my editor often says, ‘A change is as good as a rest.’

Though she also says, ‘I seem to remember we have a contractual agreement that you’ll deliver this book on time.’”

Richard Powers: “In 25 years of writing novels, I’ve never had anything that felt like writer’s block. I write the way you might arrange flowers. Not every try works, but each one launches another. Every constraint, even dullness, frees up a new design.”

Geraldine Brooks: “Because I worked as a newspaper reporter for about 14 years before attempting my first novel, I learned to write under almost any circumstances—by candle light, in longhand, in African villages where there was no power, under shelling in Kurdistan. (I was more afraid of my foreign editor, and the consequences of missing a deadline, than I was of the shelling.) So I think those experiences inoculated me against writer’s block. I can always write. Sometimes, to be sure, what I write is crap, but it’s words on the page and therefore it is something to work with.”

Gail Tsukiyama: “I try to step away from my writing, and hopefully, return refreshed. I usually pick up a book I’m reading, or go to see a movie, anything that may inspire my own work. I also find doing the mundane, everyday things in life has a calming, creative influence on me. Some of my best ideas come when I’m vacuuming or waiting in lines. Not to mention shopping therapy, it’s a reminder that there’s another world out there!”

Jess Walter: “My cure for writer’s block is to step away from the thing I’m stuck on, usually a novel, and write something totally different. Besides fiction, I write poetry, screenplays, essays and journalism. It’s usually not the writing itself that I’m stuck on, but thing I’m trying to write. So I often have four or five things going at once.”

Nancy Werlin: “I tell myself that all I need to do is open the file and work for 15 minutes. Or ten. Or five.”

Myla Goldberg: “Mostly through denial. I make myself sit down at the keyboard no matter what, no matter how terrible I feel the writing is going or how little I may be in the mood. If things are really, really bad, I give myself a day off to eavesdrop in cafes or go to a matinee or a museum or something. A day spent in the city tends to have incredible rejuvenating powers—either that or the guilt of a day spent not writing sends me back to my desk feeling ready and willing again.”

Alice Hoffman: “I didn’t believe in writer’s block until I had it. I worked on exercises— outlines, words, character studies, then moved to stories, then the stories became linked stories, then a novel. Again, when I had writer’s block after Sept. 11, I read some of my favorite books from childhood, and they reminded me why I wanted to write in the first place.”

Curtis Sittenfeld: “I don’t really believe in it. There are times I’m not in the mood to write, but I’m wary of romanticizing that. If I’m moderately not in the mood, I’ll reread what I’ve recently written to try to enter the fictional world, and I’ll give myself a manageable, very specific assignment, like writing a particular scene. If I’m really not in the mood, I’ll edit earlier work. If I'm really, really not in the mood, I’ll go read fiction by someone else. I don’t think it’s shameful to admit that some days your time can be better spent reading than writing.”

Gayle Brandeis: “I don’t fight it. I give in to it and trust that the words will surface again when they need to. If the silence starts to last a bit too long, though, or if I’m starting to feel anxious about not writing, I have a few tricks to get the juices flowing again.

One thing I like to do is crack open the dictionary, find a word I hadn’t heard of before and write a poem around it. Sometimes the poems are silly, sometimes they’re painful, but they always get me excited about writing again. I’m also partial to choosing an object—preferably edible, ideally a strawberry—and taking time to explore it slowly, mindfully, using all of my senses.

This always calms me down, wakes me up, and blasts my writing right back open.”

What’s your take on writer’s block? Do you suffer from it? How do you get through it?

Ack! I missed last week's as I was traveling etc and that always disorients me. Am now house sitting in Santa Fe for a few more days. But FYI, as a coach one of my regular type of clients were writers who became mothers then dropped off the writing world for a string of years. Then one day they woke up and thought, "Mein Gott! It's been 5 (7, 9) years since I wrote! Help!" I don't think there's any way around that gap, unless you're rich, and you're still likely to have one even if it's smaller.

Also great quotes. The one I always tell people who have an active project in mind is to just do something, take care of simple problems that are right in front of them and don't worry about the big picture. Often the big picture overwhelms, and that's when they need to go small. Just work on a scene, etc. Keep *moving*.

This probably won't shock you, but Jodi Picoult's explanation is pretty much mine: ain't nobody got time for that!

Also, folks are often impressed with my daily volume, but let's be real here: I write a good first draft every day. Most things I write could improve if edited patiently over a few days, but I just want to get them out there ASAP. I don't really care all that much about making it perfect, because the overwhelming value I provide to the world is with the ideas, not with my florid prose (at least, that's my take! I'm good with words and all that, but for me, that stuff matters way less than the idea).