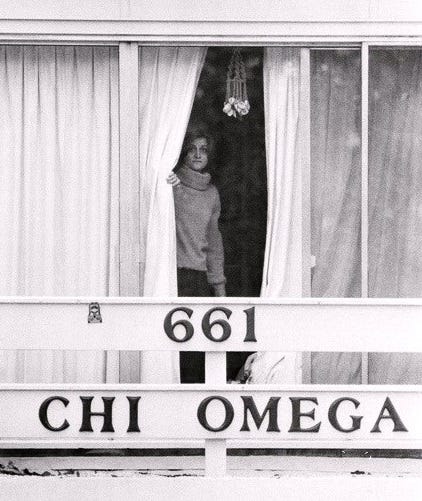

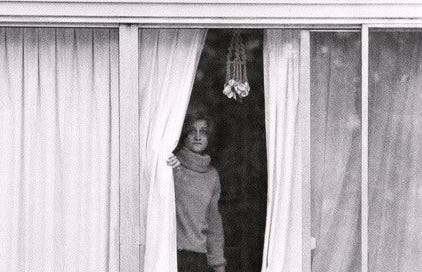

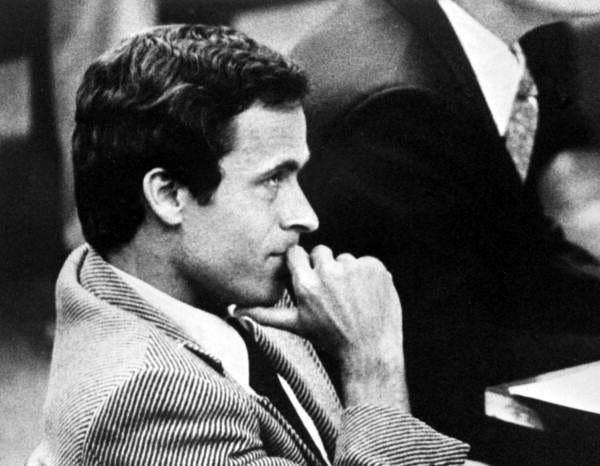

In the footage from the Ted Bundy trial in Miami for the 1978 brutal slayings of two Florida State University sorority sisters—when the handsome accused had the gumption to represent himself—I am less intrigued by the so-called star and his obvious psychopathy than his admiring audience. There are women packed into the benches of courtroom, young women the age of his college dorm victims. Giggling, trying to make eye contact and get the serial killer’s attention, not very able to articulate why they are so compelled to travel from as far away as Seattle to be there but lit up with the attempt.

In a news clip that aired on CBS News, 1979, investigating this “steady and unusual stream of spectators,” a few of this steady, unusual stream had to say:

Young woman: Every time he turns around I kind of get that feeling—oh no, you know, he’s going to get me next.

Reporter: But yet you’re fascinated by him?

Young woman: Very, very. Every night when I go to bed, I just, I get very scared. I shut my door and lock it, you know.

Or another:

I’m not afraid of him. He just doesn’t look the type to kill somebody.

According to the arguably sexist psychologist expert in the piece, this giddy girl-gathering “might be motivated by a mix of fear, intrigue and sexual attraction.”

“There’s no question but that violence does quicken the pulse of many people, and certainly of young women.”

No, I don’t think most girls are turned on by gruesome murderers, and a contemporary psychologist wouldn’t dare say such a thing. I don’t find killers attractive, but I do gravitate to some bad boy types (at least in looks) and as a true crime follower I do get addicted to the pursuit of, shall we say, fathoming. Trying to understand the incomprehensible.

The first case that got me hooked in the genre of obsessively sleuthing/staring into the darkest abyss of humanity was the most horrific story I ever heard about Chris Watts of Colorado, commonly considered an attractive, wholesome everyday good-dad type, with his social media savvy, multi-level-marketing wife, and their two cute-as-buttons daughters, ages 2 and 4. By the summer of 2018, he had gotten more buffed than his usual and had an affair for all of a month or so, which apparently inspired him to suddenly—on August 13, my daughter’s birthday—strangle his pregnant wife, and then either smother his adorable kids and drop them down small hatches in the oil tanks at work where he buried his wife nearby, or just drive the girls alive with their dead mom to work and kill them there on site before the oil tank plunge and shallow burial (he’s told multiple versions of the story).

What’s worse is even someone as despicable as this POS family annihilator gets the ladies loving on him from afar when he’s in jail until he croaks. I remember the horror of learning, soon after the fleeting relief of his quick conviction, that love letters and marriage proposals had already started to arrive for Chris Watts in prison.

It’s one thing to try to decode horrific crimes from an intellectual perspective, but to dip as deep as desiring such a sick stranger? Why oh why?

There’s a term for this and a thoughtful article about it by author Lauren Kessler, where she makes note that the reasons women love, and sometimes marry, the meanest men in the big house are “are as diverse, quirky, open-hearted, misguided, optimistic, rational, irrational, well considered and impulsive as the reasons women marry/stay married to men in the free world.” There are the MBIs (married before incarceration) who astoundingly stand by their convicted man, and the MWIs (married while incarcerated). Among the latter, along with those who just write the letters, some may have a real diagnosis, and it’s definitely not that they just find the convict’s tattoos hot:

From Wikipedia:

Hybristophilia is a paraphilia involving sexual interest in and attraction to those who commit crimes. The term is derived from the Greek word hubrizein (ὑβρίζειν), meaning “to commit an outrage against someone” (ultimately derived from hubris ὕβρις, “hubris”), and philo, meaning “having a strong affinity/preference for.”

The crazier the crime, the more this happens. And generally only to women for men. Explains Kessler:

There are women who were victims of abuse and mistreatment by fathers, previous husbands, boyfriends. These women, so the logic goes, figure that if they’re in a relationship with a man in prison, he’s not going to hurt them. He can’t hurt them. Unlike in their past relationships, they are safe.

Or there are MWI women who are calculating manipulators on a power trip. They hold all the cards. The guy is dependent on them for news of the outside, for money contributed to the canteen account, for human kindness—all of which they can dispense, or not, at will.

Or, folks, how about this: Many women who marry incarcerated men fall in love with them. That’s right. Love. Intellectual, emotional, spiritual bonding. The sharing of ideas and stories, beliefs, hopes and dreams. Humor, sadness, random observations. You know…the stuff of life. The sociologist Megan Comfort interviewed dozens of women married or involved with inmates, and she found—contrary to what we think we know—that they were not attracted to the “bad boy,” not attracted to the thrill of risky choices, but rather quite the opposite. The women she interviewed were attracted to what we would consider these men’s “feminine” qualities. The men were thoughtful and communicative. They were listeners. They were interested in establishing and nurturing a lasting emotional relationship (a sexual relationship not being possible, not now and maybe never). They were interested in finding a soul mate not a bedmate. I know two such couples. And I deeply admire their commitment to each other.

These hidden worlds are masked by stereotypes. The more we know, the less likely we are to fool ourselves into thinking we know.

No matter the female reasons, I did wonder why the men in prison, convicted of multiple life sentences for taking multiple lives, are even allowed to receive such mail and foster such real or imagined romances. But it seems they are afforded this luxury for the same reason they get to go to the prison library, or walk the yard, or have the opportunity to suddenly find God. They are allowed to retain, and maybe even grow, what’s left of their humanity.

After my last few weeks circling the drain of Limbo and then all the rings of Hell, I wonder if seeking religion moves them a bit out of this feeling of being trapped in the perennial purgatory of the in-between, punished but allowed to live in this stagnant state while those they killed have no such option. They can at least feel as if they have fallen in with a good god who might forgive—and even love—them. And to find the affection and attention of a woman, well that’s a no-brainer. I myself have been guilty of entertaining penpals I had no business still texting when I knew we’d never actually meet again. Why wouldn’t these bored, captive men write back and develop the same level of love and attachment in return.

Like Bundy and Watts, there was also Richard Ramirez (“The Night Stalker”), and “cannibal-killer” Jeffrey Dahmer receiving fan mail in jail. This “Romancing the Monster” article reminds us that Bundy, Ramirez, and Charles Manson, “would marry women they met either during their trials or following their convictions.”

Through his crimes, trials, and jail-time Ted Bundy had a longtime female friend who converted to romantic partner only after he was convicted for the co-ed murders. Of course he had to make a show of his love and pervert a legal loophole, asking the loyal Carol Anne Boone to marry him in the midst of his subsequent 1980 trial for the murder of a 12-year-old, which won him his third death penalty. Carol Anne stayed with him long enough to have a child from their illicit conjugal visits, until she did finally divorce him a few years before his execution in 1989.

From the allthatsinteresting.com piece on this:

Ultimately, Ted Bundy, the clever ex-law student that he was, figured a way to marry Carole Ann Boone while incarcerated. He found that an old Florida law stated that as long as a judge is present during a declaration of marriage in court, the intended transaction is legally valid.

According to Rule’s book The Stranger Beside Me, Bundy bungled the effort on his first try and had to rephrase his intentions differently the second time around.

Boone, meanwhile, made sure to contact a notary public to witness this second attempt and stamp their marriage license beforehand. Acting as his own defense attorney, Bundy called Boone to take the witness stand on Feb. 9, 1980. When asked to describe him, Boone classified him as “kind, warm and patient.”

“I’ve never seen anything in Ted that indicates any destructiveness towards any other people,” she said. “He’s a large part of my life. He is vital to me.”

Bundy then asked Carole Ann Boone, on the stand in the midst of his murder trial, to marry him. She agreed though the transaction wasn’t legitimate until Bundy added, “I do hereby marry you” and the pair had officially formed a union of marriage.

This take on love is love no matter the murderer, isn’t just an American phenomenon, the “Monster” article continues. Overseas, “Peter Sutcliffe (the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’) and Josef Fritzkl, an Austrian man who imprisoned and sexually assaulted his daughter in a cellar for 24 years, both received affectionate, frequently sexual, correspondence from female admirers.”

Hybristophilia, though it obviously predates its title, was coined by sexologist Dr. John Money in 1986 and defined more specifically as: “a paraphilia (sexual deviation) in which sexual arousal, facilitation, and attainment of orgasm are responsive to and contingent upon being with a partner known to have committed an outrage, cheating, lying, known infidelities, or crime—such as rape, murder, or armed robbery.”

The article asks if these women might still harbor the same feelings should their bad man get out of jail free and if the love is allowed to be less abstract and more real. Sometimes yes. There are some fascinating cases of women who are happy to help, like Carol Anne who smuggled Bundy the money that aided his escape from Colorado jail and allowed him to get to Florida for his final killing spree (though she always stood by his innocence). There was the odd couple of South Africa, Gert van Rooyen and Joey Haarhof, who between 1988-1990 “are believed to have abducted, molested, and murdered at least six young girls, though there may be many more, including children of color whose disappearances were not prominently featured in the media.” Gert had former convictions and prison time for abducting and molesting girls, which didn’t stop his new lover Joey from joining him, as if in a cult, and help lure in new girls to kill. And, more recently in Alabama in 2020, there was the case of the female corrections officer Vicky White who died helping convicted murderer Casey White (of coincidental same last name) escape.

Should we female weirdoes who only like to watch all these train wreck stories unfold from the safe distance of our homes and screens feel bad too? The author gives us sleuthing looky-loos who remain platonic a pass, and a compliment:

One thing remains certain: Women fascinated by the darkest extremes of human behavior are a far cry from those who pursue actual emotional and physical relationships with known killers—or who, in the most astonishing cases, become murderers themselves.

That said, when it comes to unraveling the complex factors that contribute to the phenomenon of hybristophilia, perhaps female true crime aficionados are perfectly primed for the challenge.

Chris Watts lived in the next town from me, this was a shocking story where he claimed innocence through a waterfall of tears into news cameras. If he gets newspaper privileges along with his love letters he will soon find that his home which had sat vacant since the killings (due to obvious reasons) just sold for 750K. Hopefully not purchased by a “fan”?

This was a fascinating read — and a timely one for me personally. I recently came across a video showing the reporting of Columbine in real-time, which was an interesting look at 1999 broadcast journalism, but it also led me down a rabbit hole to learn more, since I wasn't even yet a teenager when it happened. Along the way, I discovered that a large subset of people still hold the killers in high esteem, almost positioning them as heroes. It's such a different mindset than I would think.