Remember 100 years ago (a few weeks) when I went on a death bender and gathered all my living wills and dying docs? Well I have more to say on the matter, since I’ve been in a dark yet hopeful place where, if you might recall, I determine the details of my death in order that I might better live. A big topic for our trying times at what feels like the edge of Armageddon—but let’s take this restful weekend time to further consider our demise.

Pandemic or not, I have happily self-isolated most of my life, which only became clear to me in more recent years that that meant I was an introvert. So I took enough pride in that cool hermit identity to call my Substack “Home|body” (with an “introvert’s outreach” subtheme) for its first 1.5 years or so and hang out here on the fringe with some like-minded isolates, alone together from the comfort of our safe houses, tossing words out our windows.

I have seemed relatively public in various stages in my life—giving readings when my books came out, becoming a writing instructor at NYU for continuing ed students, working as a reporter and getting into the habit of approaching strangers to ask personal questions, emceeing at the annual benefit of the Writers Center I managed. I managed to do all these things, but not the most comfortably. Along the way I madly thought it was a good idea to open a bar—only to learn, eegads, I had built myself a stage that I was trapped behind—but even that was sort of survivable, if I could dye my hair or have a costume to help me look the part. Roleplaying the cool girl that I knew I would never be but it felt fun, with a little alco-confidence in me, to try. Maybe some swagger could trickle in by osmosis through my protective layers. Sometimes I can be a showgirl, if I feel rested and articulate and beautiful and all the stars align and the audience is just right, but sometimes I quake at the concept at being asked to speak into a microphone, of the scary concept of anybody really looking at me.

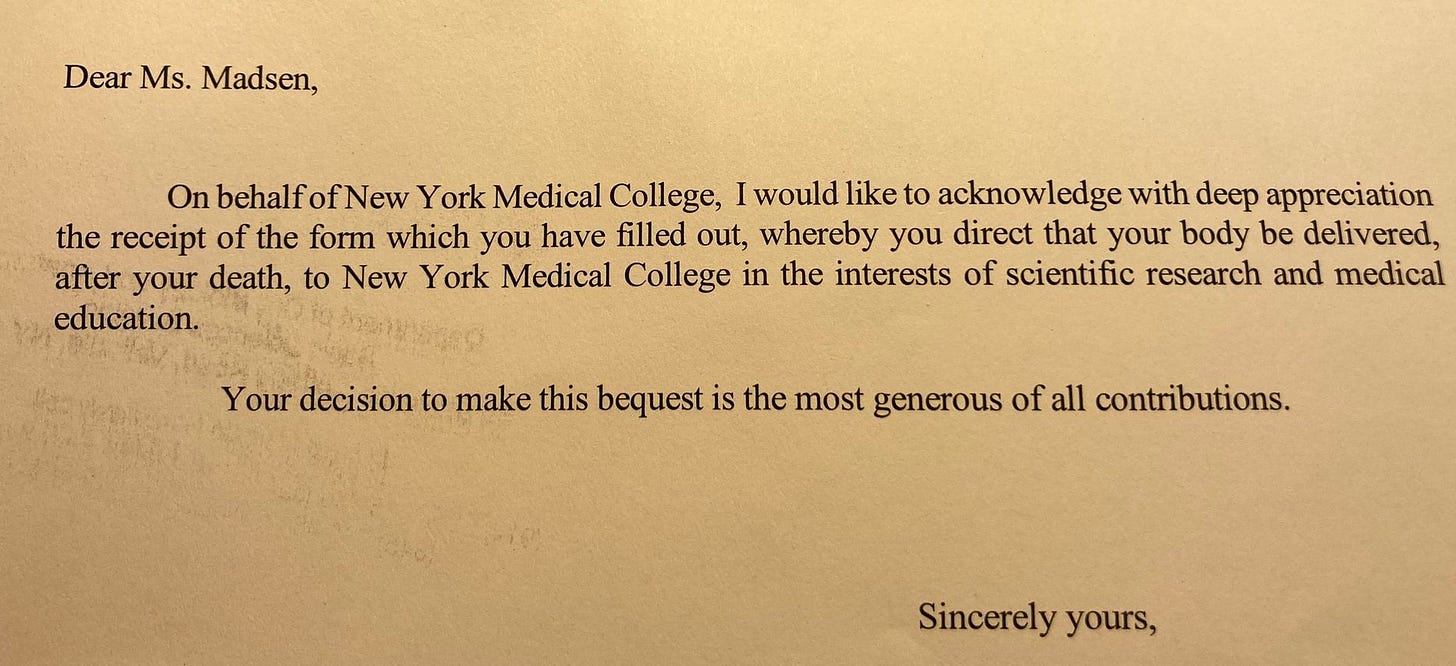

There’s an interesting conundrum I have to grapple with in my death packet. The two applications I have sent to a few nearby anatomical programs at medical colleges for the full-body donation soon boomeranged back with formal yet kind acceptance letters, like the oddest college admittance for old people:

I don’t believe in an afterlife, I don’t believe that any trace of my soul will still live in my flesh, or that the body will retain any residual consciousness, but still the thought of earnest med students peering at my naked corpse, really analyzing my every inch, not to mention whatever they’re doing with the sharp tools, gives me the heebies. The idea that this uncomfortable collective Gaze might continue after death, and there’d be no stopping it. There’s a difference between being looked at in a more cursory way vs. the terror-inducing concept of being seen. Will they giggle over my bad tattoos and my zit-scratch scars. Will they laugh at the way the toes are not tended, the belly distended (I imagine it will be, as I hope I will be old, abiding gravity, and still enjoying savory snacks). I can only wish I can live out my remaining years with increasingly less self-consciousness—as women do seem to sprout these glorious midlife wings that fly them ever-closer to wisdom and peace as they mature—and that these death contracts may seal the deal on that at last.

There’s some recurring motifs across many of the true crime podcasts I listen to or documentaries I watch. When people come across a dead body strewn on the side of the road or at the edge of the forest or wherever, they tend to think it’s a doll at first, a shop mannequin. It can’t be real, the mind revolts. It must be a toy or a prop for clothes. And why isn’t it wearing any clothes? There’s the certain kind of killer who enjoys leaving a body out for display, posing it it in this way. Like the infamous so-called Black Dahlia case of Elizabeth Short found perfectly dissected along a sidewalk in LA in 1947. Then there are the weird cases when the deceased woman/girl is found naked, as she often might be if she’s murdered after a sexual assault, and sometimes—however improbably—investigators might consider the concept that she’s died by suicide and left herself, intentionally, in that state. No woman I know would leave herself to be found naked. We’d clean our mess, we’d cover ourselves up. I don’t think I’m alone in this fear of being seen when having no control over the experience.

Fascinating as well are the no-body homicides—the murders that may just be missing persons forever as there’s no proof, no remains. And how much harder it is to prove those cases. Maura Murray, the college student, who went poof in the middle of the wintry New Hampshire road (the last trace of her the scent hound detected.) Vanished into thin air. At least, now 20 years later, if they do find her she won’t be exposed in any embarrassing way, rather just some scattered bones.

The best you can hope for is bones.

There was the story in the background of my October Show and Tell event that didn’t get told publicly. How my friend Michael Baker, owner of Ichabod’s head, revealed to me that teens, circa 1985, had dug up a body from our famous cemetery for reasons unknown, leaving some woman unearthed and exposed. He told me, “I was in Sleepy Hollow Court on a real estate matter and all of a sudden as I was waiting for my case the bailiff brings two boys in who were arrested for digging up a woman in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery and laying her body next to the grave.”

Those were the days? Nowadays you’ll get taken to court if you so much as try film in the cemetery without explicit permission, though I imagine if teens performed such an unburial feat now it would go viral on TikTok. I had all kinds of questions about that story (who was this poor woman? was she…fresh? why?), but alas, there’s no trace online.

There’s the body that taunted a mourning mother for decades. Into the Fire is quite the doc on Netflix. Cathy Terkanian, who had a baby at the age of 16, was convinced to put her daughter up for adoption when the baby was nine months old. Thirty-six years later Cathy learns, in a letter from the adoption agency, that her daughter Aundria had been missing for the last 21 years—since 1989, age 14. The documentary begins with that fact and follows this mom on her relentless mission to track what happened to her daughter, right to her remains. A mother’s intuition and the engine of film crew is a powerful force. They learn that the adopted father, Dennis Bowman, was the killer, and though his story changes from jail about the murder and the victim’s whereabouts, Cathy is certain her girl is buried right in Dennis’ wife’s backyard. She knows the exact spot, she just knows. And she turns out to be exactly right. So many years after the fact, they are finally able to dig, and there she was. Found at last, though it’s not a pretty place to end up. From an article in Time Magazine:

Throughout the docu-series, Dennis changes his story in letters—read by an actor—and phone calls exchanged with [wife] Brenda while he was in prison. In one key phone call excerpted in the film, he tells Brenda that Aundria is actually buried in her backyard. The authorities sent a bulldozer to the property, and the bulldozer turned up the barrel that Dennis was talking about. The remains were found in a trash can of diapers and a Peppermint Pattie candy wrapper that had the date 1989, the year Aundria disappeared.

Unbelievably, the mom had to fight to receive only half of her daughter’s ashes after they cremated the remains. Still she had this partial daughter; just never all of her. The indignity of having to share the daughter with the woman who protected her guilty husband all this time.

And the word remains; how that never sounds right. The moment in these shows where they dig and find something left of a loved one is always so wrenchingly emotional, so much more than the sum of the tattered, ruined parts. Remains mean far more to the living than they might to the dead who don’t know the difference—ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Decomposition that might, in a form of reincarnation, nurture a plant. I believe in this sort of transfer of energy, on the cellular level, the science of the circle of life. But if you’re stuck in a plastic barrel, perhaps you might linger on entrapped, dissatisfied. And no matter the outcome, I don’t want to see it. I didn’t enjoy my grandparents’ open caskets with the plasticity of puffed out embalmed faces that didn’t seem to match up.

This isn’t a pretty story, but I’ll admit: remember that cat of mine I had for 18 years and nine lives and buried in the Catskills? Well she’s there no more. Add to her history some handful of post-deaths in the effort to get her remains “righted.”

She died at the vet by lethal injection because of her cancer a day before we were scheduled to go camping in the Catskills. We decided to bring her “remains” (a full-fledged cat) to bury on our own land upstate on the way. Don’t tell my kids, but this required (since it was summertime) stowing her—in a bag in the blanket she died in—in the freezer overnight. I didn’t want anyone to complain about any smells on our road trip. In the morning we drove to our land and started digging alongside her in a cardboard box. My kids composed cards for her and brought along one of her toys. Of course it’s difficult to dig in this rocky dirt, but I made a big enough hole and we had a little ceremony, and laid our Poe, peacefully we thought, to rest. She was wrapped in the blanket she died in, because I couldn’t bear seeing her again in this way, wanting to remember her alive in her last moments rather than as a corpse. She had a great resting spot, capped with a cat statue, with a beautiful view, in a place she seemed to have enjoyed visiting a few times. She was even near a real cemetery here, so might have friends, if human. I didn’t imagine a fox would come and sit at the stone marking her spot, as if paying respects. My neighbor asked if we did something back there because that fox would hang out often. Yes, in fact, we buried our dear cat. RIP.

And so it would go forever this way, I thought. Someday I even imagined my kids would add to this serene scene and put some of my ashes into a chamber of a windchime and hang me from a cemetery tree with the historic Lanes from Lanesville. But life isn’t so predictable. Suddenly, I found myself wanting to sell the land I thought I would own forever and pass down to my kids and future generations. I wanted more, bigger land (i.e. less neighbors), and could—for the same amount of money I thought I could get for this—buy a parcel of twice the acreage (complete with treehouse!) further up the road. Suddenly, I had to deliberate over what to do about my dead. Do we leave Poe behind, in communion with her fox? Or do we have to disturb her and bring her with us? How? And what then, when I decide in however many years time, that I want a different bigger parcel again. I can’t keep moving this poor Poe. My daughter insisted the cat come with us.

Teen-cemetery-style, my friend and I went on a covert mission to dig up the cat, on a frozen day when the ground proved even more impossible. The shovel immediately snapped at the handle. My friend helped unearth her on his knees with the broken spade. It was not at all what I expected—not a blanket bundle lightened with depleted bones at this point, but, as he reported to me because I couldn’t look, her full self wrapped, soaked in water that was pooling at the bottom of the hole. It was a terrible place to be and suddenly the mission changed. She needed to move because this was not good. I had dumbly left her in a synthetic blanket; Poe would never decompose properly this way. We were now “doing the right thing” to rescue her from the equivalent of Aundria’s awful barrel. Me with my best intentions needed rerouting.

We were moving my yard tools and such to the new land that day, but hadn’t closed on the deal officially yet; the owners were just affording me a favor. I couldn’t just bury my cat on land not yet mine, and also: frozen ground, broken shovel. It would be impossible. I couldn’t bring this wet intact being home to haunt my kids and ruin our lives. We had to cremate her. So suddenly, a quick drop-by at my new place that isn’t mine yet becomes the odd site of a funeral pyre we make in the fire pit. My friend somehow knew how to perform this in a respectful way in which I didn’t have to see anything, and soon there were bones we could have now, stunning white, hollow bones that we could pick out of the ashes of that damn synthetic blanket. It was no longer gruesome, it was beautiful. Something I could see and touch like shells from the beach. I could regather her parts and bring her home. Then what? The bones are so delicate, they pulverize instantly with a mortar and pestle to create the kind of ashes my kids might expect from such an event. I put them in a little silver old film jar, same as their grandpa Elmer (who I did not pulverize by hand). It wasn’t hard anymore to see her and interact with her in this state. It felt dignified. Corrected. All of this journey made necessary only because I was afraid to see her initially, to unwrap her body and put her in the natural cloth she needed.

I’m embarrassed to share this tale, and worried how nuts you will think I am communing with my cat bones like this, but better now perhaps than at my death, when you discover it in words left behind?

For then there’s the ultimate death question for a writer. What will become not only of my body, but the body of my work. The thousands and thousands of pages of words that I have amassed in my lifetime and shared (often only to myself). There’s always been a sense of over-my-shoulderness about the act, even when only writing a journal entry, the haunting idea of a Future Reader. The what if. Someday someone might find this when I’m gone. And how will that be? How do I feel about that? It’s as scary as being physically present, maybe more so. A whole different level of nudity. Not only being seen but being read, to the depths of my secrets and most private darkest thoughts, all the anger, all the heartbreak, all the raw ugliness. Usually I’ve only been compelled to journal at the extremes—the saddest, or the giddiest. In or out of love. In pain or in the throes of early obsession. Usually more of the pain. Will they think I’m manic; or worse, tragic? Should I censor myself?

Should I go through this human pile—the dozens of hardbound journals through the years since youth, the bins filling cabinets in the living room, the file folders, and rising up to the attic. Fiction, essays, hand-written letters back when I had penpals (letters received, or never sent). Perhaps a useful exercise to review it all someday. Would discarding be kinder? Leaving less trace? The last thing, as the child of hoarders, I want to do is leave any messes for my kids to deal with. Or does it mean if I destroy the evidence now, that they might never truly know me?

What an odd balance in the introvert writer of desiring both hiding and being understood. What you might learn of me by the time I’m gone: Look, she’s afraid—of everything!—and therefore very brave.

[Appreciate what I produce here but don’t feel like committing to a paid subscription? Spare some change to Buy Me a Book.]

I don’t think you’re weird at all for going through all you did for Poe and your girls and yourself. I think it’s kind of beautiful. And I’m really glad you had help.

It's different and not as extreme, but if it makes you feel better I still have my beloved parrot's bird cage. I've had people tell me that was wrong; I've told them to go fk themselves (okay, not that harshly, but still).

Some of your thoughts here make me wonder if I've forced my pretty woo-woo essay on you, because I'm pretty woo-woo, really. Just built that way. There's an experience at a river when I was young, and then an event, and then madness and the clawing-out-of. For some reason I'm wanting people to read it these days. (I got fan mail about it.)